Cambodian Committee Charts Road Map to Water Security

The inaugural meeting of the Stung Chinit River Basin Management Committee brought together Cambodian leaders to address shared threats to water security.

Even before the disaster, decades of population growth and industrialization had degraded the Rhine River so thoroughly that it was known as “the sewer of Europe.” Then one early morning in 1986, a factory caught fire in Switzerland. Tons of toxic chemicals flowed into the river, which runs through six European countries, wiping out nearly all biological life in its water.

Yet fast forward to today and water quality has improved considerably. Fish populations have almost rebounded to their level before the chemical spill, and almost all of the 58 million inhabitants of the Rhine catchment are connected to urban wastewater treatment plants. What can we learn from the Rhine’s example? That good governance, river management and cooperation can preserve and rehabilitate waterways that face seemingly overwhelming challenges.

That was the message of Robert O’Sullivan, interim project director for the USAID-funded Sustainable Water Partnership (SWP), to community and government officials who have joined a new river basin management committee to manage water resources in one of the Cambodia’s most at-risk watersheds. The Stung Chinit River Watershed in central Cambodia faces increasing threats due to climate change, deforestation, agricultural use, and pollution from agriculture and the mining industry.

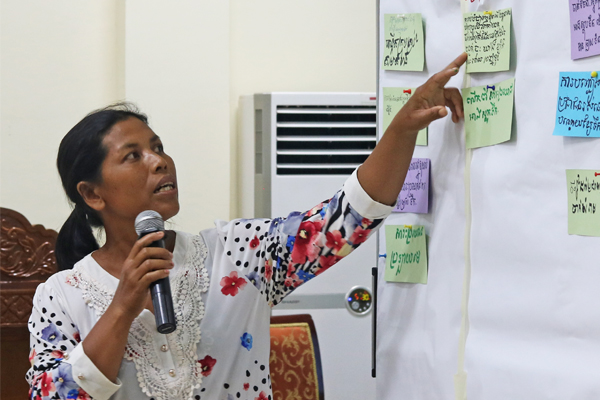

SWP, which is implemented by Winrock International, is supporting the committee as it addresses these challenges. Comprised of 27 members representing the government as well as industry, farming, forestry and fishery groups, the committee held its inaugural meeting April 30 in Kampong Thom, the province encompassing the Stung Chinit River Watershed.

Following in the footsteps of committees such as the one that restored the Rhine, analysis of a wide cross-section of countries and river basin management organizations suggests five features of best practice to achieve results in river basin management, O’Sullivan said.

The process begins with establishing a river basin-wide institutional framework that allows all the main government administrations operating within the basin to participate. Facilitated by SWP, that first hurdle was cleared in early April when H.E. Sok Lou, the governor of Kampong Thom, signed a decree establishing the committee. Lou chairs the committee and opened the inaugural meeting by emphasizing the importance of diverse viewpoints within the committee, because the water problems affect every person who lives in the watershed and thus a collective solution.

“[This] water resource is crucial for everybody,” Lou said. “The water quality has to be controlled, and the pollution from other human activities has to be measured too in order to make sure that the water is clean and safe for people. We have to protect it in advance before something [worse] happens.”

Bunnara Min, the team leader for SWP Cambodia, said the committee would play a crucial role in this goal.

“The committee provides all key stakeholders with a platform to share their views on water related risk, water security concerns, [and] innovative solutions,” Min said.

In addition to government officials, the committee includes participation from local water users from community forestry, farming and fishing groups. Together, they will serve as the primary body to strengthen governance, define policy and identify activities to improve social resilience and strengthen water security.

Continuing with best practices for river basin management, the next step is continuing to establish scientific knowledge of the conditions in the basin. Thus far SWP has conducted studies and assessments to determine conditions such as water quality, biodiversity and the state of irrigation infrastructure and management in the area. Information on the current and future vulnerabilities of water resource management in the watershed was developed using a tool called the Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) model.

Planning and management processes must also incorporate participation from all water users and community members, which is a major reason for the presence on the committee of local residents from community forestry, farming and fishing groups.

“Stakeholder engagement is not a ‘one off’ exercise,” O’Sullivan said. “It is an ongoing process that needs to continue with multiple stakeholders and across sectors including farmers, fishers, foresters, private sector, academia, research institutions and other important stakeholders.”

Policies, strategies, decisions and projects need to be developed in concert and with the understanding that natural resources are interconnected. SWP has facilitated the start of this process by preparing a strategic framework for management of the Stung Chinit River Basin. But this integration needs to be built into how institutions interact, how policy is developed and how resources are managed. Ultimately, the fundamental responsibility to develop and implement policies rests with the committee.

Finally, a system must be established to assess whether or not the river basin is being managed sustainably. A good monitoring and auditing program can help to create or reinforce accountability among the key organizations and their staff. The committee will need to work out how to build on existing systems and data to monitor progress and ensure accountability.

“Water security problems cannot be solved by science or technology alone,” O’Sullivan said. “They are instead human problems of governance, policy, leadership and social resilience. We have the pieces in place to address these challenges.

“We have seen leadership from the governor, H.E. Sok Lou, to sign the decree to establish this committee, and look to his continued leadership moving forward,” O’Sullivan continued. “This committee is the primary body to strengthen governance, define policy and identify activities to improve social resilience and strengthen water security. It is up to committee members to own these responsibilities and move the agenda forward … as the future water security of the Stung Chinit is up to [the committee].”

Related Projects