Erythrina sandwicensis – Unique Hawaiian NFT

NFTA 92-06, October 1992

A quick guide to useful nitrogen fixing trees from around the world

Erythrina sandwicensis, commonly known as wiliwili, is the only Erythrina endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. The wood, seed and flowers were traditionally used in Hawaii, and the tree is integral to many Hawaiian legends and proverbs. A unique characteristic of the species is the flower color variation within natural populations. Wiliwili is adapted to and lowland environments and has potential for revegetation of degraded sites.

BOTANY

BOTANY

Erythrina sandwicensis Degener (syn. E. monosperma Gaud) is closely related to both the E. tahitensis and E. velutina (Neill 1990). Erythrina sandwicensis is a small deciduous tree 5-15 m tall with a short, stout, crooked or gnarled trunk 30-90 cm in diameter. Spreading branches are stiff, and the broad thin crown is wider than it is high. A champion tree measured on the Island of Hawaii in 1968 was 16.8 m tall with a trunk circumference (cbh) of 3.8 m.

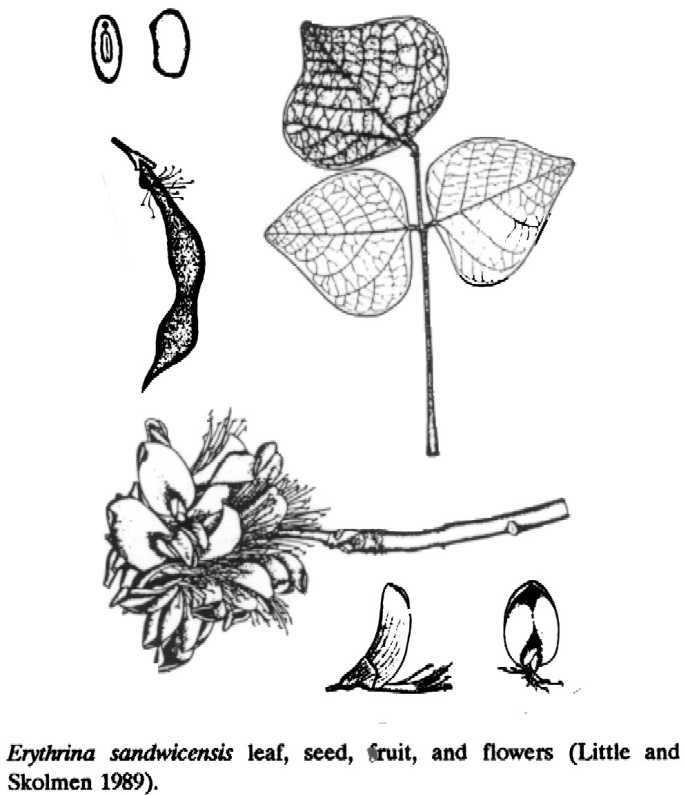

The bark is smooth, light to reddish brown, and has scattered stout grey or black spines up to 1 cm long. With age, it becomes slightly fissured and thin. Twigs are stout, green with yellow hairs when young and have scattered blackish spines. Leaves are alternate, compound, 13-30 cm long, with a long slender leafstalk. The three leaflets are short-stalked. The end leaflet is larger than the other two. Leaflets are 4-10 cm long and 6-15 cm wide (Little and Skolmen 1989).

Flower clusters (racemes) are on hairy yellow stalks of 7.4 cm or less. Flowers are crowded in a mass and are 7.5-15 cm long and short stalked. Flower color within natural populations can include orange, yellow, salmon, green and white (Little and Skolmen 1989). This striking color variation is probably unique within the genus (Neill 1990).

Reports vary on flowering and leaf fall. Rock (1913) reported that wiliwili loses its leaves in the late summer or early fall (August to October), and leaves appear again during early spring to mid-summer (March to July), usually after flowering has occurred. Observations on Maui indicate that leaves drop during the dry periods of late spring or early summer (May to June). The tree flowers during the fall (September to November). Leaves reappear after the first southerly storms in the late fall (November)

(B. Hobdy, Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, personal observation). Differences in observations may be tied to variation of annual soil moisture, and the considerable heterogeneity of flowering, leaf loss, and seed set within a single stand.

Fruits (pods) are approximately 10 cm long and 13 cm broad, flattened, and pointed at both ends. They are blackish and slightly narrowed between seeds. Mature pods are found on the trees during winter months (December to February). Pods contain 1-4 elliptical, shiny red orange seeds 13-15 mm long (Little and Skolmen 1989).

ECOLOGY. Wiliwili occurs near sea level to 610 m altitude in and regions (Little and Skolmen 1989). Annual rainfall in these areas ranges from 500 to 1250 mm and is usually concentrated between November and March. Once an important component of ancient endemic Hawaiian dryland forests (Rock 1913), wiliwili has been replaced by Prosopis pallida in many areas (Little and Skolmen 1989). However, the species is not in danger of extinction.

DISTRIBUTION. Wiliwili is endemic to the leeward side of the Hawaiian Islands (Little and Skolmen 1989). It is not known to have been introduced elsewhere.

USES. Wood: The wood is reported to be the lightest of Hawaiian wood. It was used for surfboards (Neal 1965), canoe outriggers, and fish net floats, (Degener 1973, Neal 1965). Degener (1973) reports that the practice of using wiliwili wood for outriggers was abandoned because Hawaiians believed that sharks followed such canoes. They also believed that trees bearing orange-red flowers possessed more durable wood than those bearing lighter colored flowers (Degener 1940).

Other uses: The bright red seeds were used for making leis (Rock 1913). Captain Cook was reportedly given a lei made of wiliwili seed when he visited the islands in 1778 (Little and Skolmen 1989). Wiliwili has been planted as living fences (Degener 1940). The species is strongly linked to Hawaiian culture through legends and proverbs. One legend refers to the different appearances of this species in the transformation of three sisters into wiliwili trees. A bald sister becomes a tree with no leaves, a sister with wind-tossed hair becomes a tree with fluttering leaves, and a hunchbacked sister becomes a gnarled tree (Neal 1965).

Land rehabilitation: Wiliwili is now being used in revegetation programs using endemic species to rehabilitate highly eroded areas in Hawaii. It survives extended drought and high winds, but growth is slow under such harsh conditions.

SILVICULTURE. Propagation: Wiliwili can be easily propagated by seed or vegetative cuttings. To improve germination, the seeds should be mechanically scarified by nicking the seed coat, and soaked in water (at room temperature) overnight. For nursery propagation 1 liter containers with a 1:1:1 mixture of perlite, vermiculite, and potting soil are suggested. A small amount of 14- 14-14 N-P-K slow release fertilizer can be added to the potting mix (Chapin 1990). If vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal (VAM) inoculant is available, it should be mixed in the potting media as well. Plant seeds 4 cm deep. Inoculate with rhizobia by irrigating the seedings with a suspension of peat inoculant in water. Keep seedlings in a shady area until the first 2 or 4 true leaves appear. Water as needed. Overwatering may cause damping-off. After two weeks, place plants in the full sun. Water with a liquid fertilizer solution containing N- P-K plus micro-nutrients. Moderate fertilizer use will not adversely affect the microsymbionts.

Methods for vegetative propagation of Erythrina variegata (Rotar et al. 1986) may be used for wiliwili. Rotar recommends that cuttings be a minimum of 2.5 cm in diameter and 30 cm long. Before planting, cuttings should air dry, or cure, for at least 24 hours. The base of the cuttings can be coated with rooting hormone. The cuttings should be placed in the ground to a depth of at least 15 cm, and the soil kept moist. Sealing the top surface of the cuttings with wax or tree-wound dressing will help to prevent drying out.

Establishment: Wiliwili should be planted on sites similar to its natural environment. Sites are recommended that have well-drained soil and receive full sun. Seedlings are ready for outplanting when stems are sturdy and well hardened, after approximately four months in the nursery. Planting holes should contain slow release fertilizers as recommended by soil nutrient analysis. If possible, water once a week for the first month. If watering is not possible or if conditions are particularly harsh, the leaves of the seedlings may be trimmed or the tops cut off entirely.

SYMBIOSES. Wiliwili forms a nitrogen fixing symbioses with Bradyrhizobium species. Highly effective strains have been identified (van Kessel et al. 1988). Rhizobial inoculants are available from NifTAL, 1000 Holomua Rd., Paia, HI, 96779 USA.

In highly eroded soils in Hawaii, inoculation of wiliwili with VAM species Glomus fasciculatus resulted in significantly increased plant growth and decreased requirements for phosphorus amendments. This indicates VAM symbioses is critical to plant success in phosphorus infertile soils.

LIMITATIONS. Wiliwili seedlings may be susceptible to damping-off problems. Powdery mildew fungi will attack the leaves in humid environments. Stem boring caterpillars have caused seedling mortality. Red spider mites are commonly associated with wiliwili. The tree is not suited for areas with high rainfall.

References

Chapin, M.H. 1990. April plant of the month – Hawaiian 1990. Kauai, Hawaii (USA): Hawaii Plant Conservation Center of the National Tropical Botanical Garden.

Degener, O. 1940. Flora Hawaiiensis: Leguminosae. Honolulu, Hawaii (USA): O. Degener.

Degener, 0. 1973. Plants of Hawaii national parks illustrative of plants and customs of the South Seas. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Braun-Brumfield.

Little, E.L. and R.G. Skolmen. 1989. Common forest trees of Hawaii (native and introduced).

Agricultural Handbook 679. Washington, D.C.: USDA.

Neal M.C. 1965. In Gardens of Hawaii. Special Publication 50. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press.

Neill, DA. 1990. Erythrina. pp 671-2. In.- W.L. Wagner, D.R. Herbst and S.H. Sohmer (eds). Manual of the flowering plants of Hawaii, Vol 1. Special Publication 83. Honolulu, Hawaii: Bishop Museum Press.

Rock, J.H. 1913. The indigenous trees of the Hawaiian Islands [USA]. Reprinted in Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle.

Rotar, P.R., RJ. Joy and P.R. Weissich. 1986. “Tropic Coral“- tall Erythrina (Erythrina variegate L.). Research Extensions Series 072. Hawaii Institute of Tropical Agriculture & Human Resources. University of Hawaii. Honolulu, Hawaii.

van Kessel, C., J.P. Roskoski and K. Keane. 1988. Ureide production by N2,-fixing leguminous trees. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 20:891-7.

Written by M.H. Powell1 and P.L. Nakao2. 1Program Director for the Americas, NFTA, 1010 Holomua Road, Paia, Hawaii, 96779, USA. 2Research Associate, NifTAL, 1000 Holomua Road, Paia, Hawaii USA.

A publication of the Forest, Farm, and Community Tree Network (FACT Net)