Adenanthera pavonina – an underutilized tree of the humid tropics

NFTA 96-01, January 1993

A quick guide to useful nitrogen fixing trees from around the world

Adenanthera pavonina (L.) (family Leguminosae, subfamily Mimosoideae) has long been an important tree in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Cultivated in home gardens and often protected in forest clearings and village common areas, this useful tree provides quality fuelwood, wood for furniture, food, and shade for economic crops like coffee and spices. The tree has been planted extensively throughout the tropics as an ornamental and has become naturalized in many countries. The scientific name is derived from a combination of the Greek aden, “a gland,” and anthera, “anther”; alluding to the anthers being tipped with a deciduous gland. The tree is known by a host of common names, including red-bead tree, red sandalwood, and Circassian-bean in English; raktakambal (India); saga (Malaysia); lopa (Samoa and Tonga); coralitos, peronias, and jumble-bead (Caribbean).

Botany

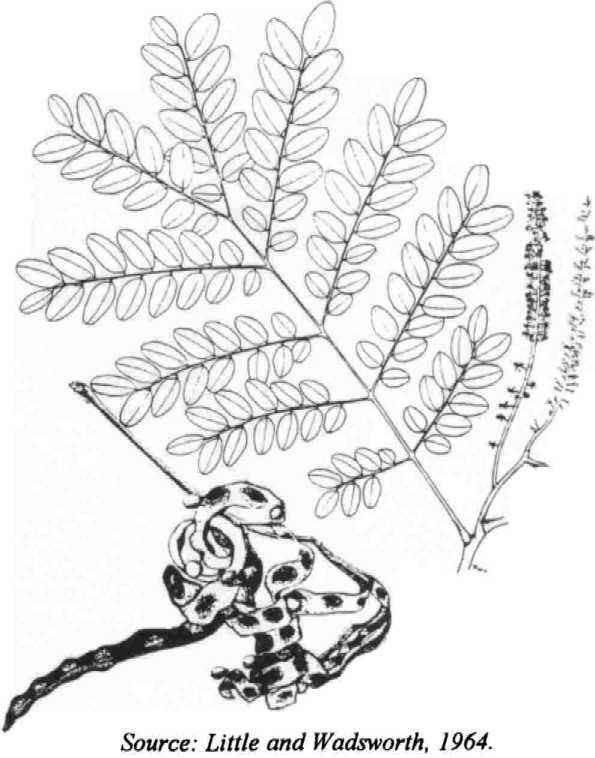

A medium- to large-sized deciduous tree, A. pavonina ranges in height from 6-15 m with diameters up to 45 cm, depending upon location. The tree is generally erect, having dark brown to grayish bark, and a spreading crown. Multiple stems are common, as are slightly buttressed trunks in older trees. The leaves are bipinnate with 2-6 opposite pairs of pinnae, each having 8-21 leaflets on short stalks. The alternate leaflets, 2.0-2.5 cm wide and 3 cm long, are oval-oblong with an asymmetric base and a blunt apex, being a dull green color on top and a blue-green beneath. The leaves yellow with age.

Flowers are borne in narrow spike-like racemes, 12-15 cm long, at branch ends. They are small, creamy-yellow in color, and fragrant. Each flower is star-shaped with five petals, connate at the base, and having 10 prominent stamens bearing anthers tipped with minute glands.

The curved pods are long and narrow, 15-22 cm by 2 cm, with slight constrictions between seeds, and dark brown in color turning black upon ripening. The leathery pods curve and twist upon dehiscence to reveal the 8-12 showy seeds characteristic of this species. The hard-coated seeds, 7.5-9.0 mm in diameter, are lens-shaped, vivid scarlet in color, and adhere to the pods. The ripened pods remain on the tree for long periods and may persist until the following spring.

There are reportedly 1600 seeds per pound (Little and Wadsworth 1964).

Ecology

This species is common throughout the lowland tropics up to 300-400 m. Adenanthera pavonina is a secondary forest tree favoring precipitation ranging between 3000-5000 mm for optimal growth. Found on a variety of soils from deep, well-drained to shallow and rocky, this tree prefers neutral to slightly acidic soils. Initial seedling growth is slow, but rapid height and diameter increment occur from the second year onward. The tree is susceptible to breakage in high winds, with the majority of damage occurring in the crown. Rapid resprouting and growth following storm damage has been recorded in the Samoan Islands (Adkins 1994).

Distribution

Adenanthera pavonina is endemic to Southeast China and India, with first reports being recorded in India. The tree has been introduced throughout the humid tropics. It has become naturalized in Malaysia, Western and Eastern Africa and most island nations of both the Pacific and the Caribbean.

Uses

There are historical accounts from Southeast Asia and Africa of using all parts of tree for traditional medicines (Burkill 1966, Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk 1962). Adenanthera pavonina is extensively cultivated as an ornamental for planting along roadsides and in common areas. The fast growth and spreading crown of light, feathery foliage offer attractive shade. Interplanted among field and tree crops (spices, coffee, coconuts), along field borders as part of a windbreak or in plantation, A. pavonina is a valuable agroforestry species (Adkins 1994, Clark and Thaman 1993).

Wood Products. Adenanthera pavonina is esteemed for fuelwood in the Pacific Islands, often being sold in local markets. The wood burns readily producing significant heat, and is used in both above- and below-ground ovens. Good sized fuelwood, larger than 11 cm in diameter, can be produced in five years. The wood is hard and durable having red-colored heartwood with light-grey sapwood. It is close- and even-grained, making it useful for constructing furniture, cabinets, and decorative wood products (Benthall 1946, Clark and Thaman 1993). It is also valued for home building.

Seeds. Known as “food trees” in Melanesia and Polynesia, the seeds of this tree are roasted over a fire and eaten by children and adults alike. Nutritional studies have shown one quarter of the seed weight to be oil with a high percentage of protein, and a fatty acid composition favoring high digestibility for both humans and livestock (Balogun and Fetuga 1985, Burkill 1966). Historically, the seeds were used as weight measures for jewelry and goldsmithing due to their small variation in weight (Benthall 1946, Burkill 1966). The bright red seeds are still used today in fashioning necklaces and decorative ornaments.

Foliage. The small leaves breakdown easily making for good use as a green manure. As a supplemental source of fodder, the leaves are fairly high in digestible crude protein (17-22%), but low in mineral content (Rajaguru 1990).

Silviculture

The tree is cultivated from seed. The seed coat is extremely hard and requires scarification if even germination is to occur. Untreated seeds can be stored up to 18 months without losing viability (Basu and Chakraverty 1986). Manual scarification, immersing the seeds in boiling water for one minute, or treatment with sulfuric acid has shown to significantly increase germination percentage. Following treatment, seed can be directly sown in the field or in a nursery. Germination occurs within 7-10 days with young seedlings obtaining a height of 8-15 cm in approximately three months. Seedling maturity occurs two to three months later at 20-30 cm in height. Nursery stock transplants well.

Growth is initially slow, but increase rapidly after the first year. Following the first year of establishment, average annual growth rates of 2.3-2.6 cm in diameter and 2.0-2.3 m height have been recorded in American Samoa (Adkins 1994). Trees planted 1 x 2 m apart for windbreaks, and at a spacing of 2 x 2 m in plantations can be thinned in three to five years to provide fuelwood and construction materials. As a shade tree, spacing varies from 5-10 m depending on the companion crop and site. The trees resprout easily allowing for coppice management with good survival.

Despite an inability to suppress weeds, the seedlings are rather hardy and can survive with minimal maintenance. Adenanthera pavonina is compatible with most tropical field and tree crops, allowing for their usage in integrated production systems.

Symbioses

Although Allen and Allen (1981) indicate the inability of A. pavonina to nodulate, this legume is generally considered to be nitrogen-fixing. Sparse, fast growing, brown nodules with isolates confirmed to be Rhizobium have been observed by Lim and Ng (1977). The author observed root nodules, both in old nursery stock and in the field, during research conducted in American Samoa. Norani (1983) confirmed the presence of VA mycorrhiza on the roots of nursery stock.

Limitations

Despite its susceptibility to crown damage in high winds, the ability to recover is remarkable. No insect or disease problems have been reported.

Research

Additional investigation concerning the nitrogen-fixing ability on native and naturalized populations is required. Continued research on fuelwood production and fodder usage is necessary.

References

Adkins, R. v-C. 1994. The role of agroforestry in the sustainability of South Pacific Islands: Species Trials in American Samoa. MS. Thesis, Utah State University. Logan, Utah. 133 p.

Allen, O.N. and E.K. Allen. 1981. The Leguminosae: a source book of characteristics, uses, and nodulation. University of Wisconsin Press. Madison, Wisconsin. 812 p.

Balogun, A.M. and B.L. Fetuga. 1985. Fatty acid composition of seed oils of some members of the Leguminosae Family. Food Chemistry, 17(3): 175-82.

Basu, D. and R.K. Chakraverty. 1986. Dormancy, viability and germination of Adenanthera pavonina seeds. Acta Botanica Indica, 14 (1): 68-72.

Benthall, A.P. 1946. Trees of Calcutta and its neighborhood. Thacker Spink and Co. Calcutta. 513 p.

Burkill, I.H. 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay peninsula, 2 ed., Volume 1, A-H. Government of Malaysia and Singapore. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 1240 p.

Clark, W.C. and R.R.Thaman. (eds). 1993. Agroforestry in the Pacific Islands: Systems for sustainability. United Nations University Press. Tokyo, Japan. 279 p.

Lim, G. and H.L. Ng. 1977. Root nodules of some tropical legumes in Singapore. Plant and Soil, 46: 317-27.

Little, E.L. Jr. and F.H. Wadsworth. 1964. Common trees of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Agriculture Handbook No. 249. USDA Forest Service. Washington, D.C. 144-46 p.

Norani, A. 1983. A preliminary survey on nodulation and VA mycorrhiza in legume roots. Malaysian Forester, 46: 171-74.

Rajaguru, A.S.B. 1990. Availability and use of shrubs and tree fodders in Sri Lanka. In: Devendra, C. (ed). Shrubs

and tree fodders for farm animals. International Development Research Centre. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. pp: 237-43.

Watt, J.M. and M.G. Breyer-Brandwijk. 1962. The medicinal and poisonous plants of southern and eastern Africa, 2 ed. E & S Livingstone, Ltd. London, England. 1457 p.

Written by Richard Van-C. Adkins, Forestry Consultant, PO Box 1433, Safford, Arizona 85548-1433 USA