Sissoo – The Versatile Rosewood

NFTA 89-07, December 1989

A quick guide to useful nitrogen fixing trees from around the world

Dalbergia sissoo is best known internationally as a premier timber species of the rosewood genus. However, sissoo is also an important fuelwood, shade, shelter and fodder tree. With its multiple products, tolerance of light frosts and long dry seasons, this species deserves greater consideration for agroforestry applications.

BOTANY

BOTANY

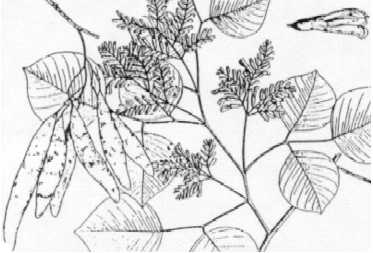

Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. (Leguminosae, subfamily Papilionoideae) is a medium to large deciduous tree with a light crown. It can grow to 30 m in height and 80 cm in diameter, but is usually smaller. Trunks are often crooked when grown in the open. Leaves are alternate, pinnately compound and about 15 cm long. Flowers are whitish to pink, 1 cm long and in dense clusters 5-10 cm in length. Pods are oblong, flat, thin, 3-7 cm long, 10-12 mm wide, and light brown. They contain 1-5 flat bean-shaped seeds 7-9 mm long. Sissoo and shisham are common names for Dalbergia sissoo.

ECOLOGY

Sissoo is native to the foothills of the Himalayas of India, Pakistan and Nepal. It is primarily found growing along river banks below 900 m elevation, but can ranges naturally up to 1500 m. The temperature in its native range averages 12-22°C, but varies from just below freezing to nearly 50°C. An average annual rainfall of 500 to 2000 mm is distributed in a monsoonal pattern with droughts of 3-4 months. Soils range from pure sand and gravel to rich alluvium of river banks; sissoo can grow in slightly saline soils. Seedlings are intolerant of shade.

TIMBER. Sissoo is among the finest cabinet, furniture and veneer timbers. The heartwood is golden to dark brown, and sapwood white to pale brownish white. The heartwood is extremely durable (Specific Gravity = 0.7- 0.8), and is very resistant to dry-wood termites; but the sapwood is readily attacked by fungi and borers.

FUELWOOD The calorific value of the sapwood and heartwood of ” excellent fuelwood is reported to be 4908 kcal/kg and 5181 kcal/kg, respectively (Anon. 1952). As a fuelwood it is grown on a 10 to 15-year rotation (NAS 1983). The tree has excellent coppicing ability, although a loss of vigor after two or three rotations has been reported in Nigeria (NAS 1983). Sissoo wood makes excellent charcoal for heating and cooking.

FODDER. Leaves and young shoots of sissoo are an important winter fodder in some areas and an emergency fodder in others. They are eaten readily by many animals, including monkeys. On a dry weight basis, leaves contain 12.6-24.1% crude protein, with young leaves having the higher values, and 123-26.1% crude fiber. Dry matter digestibility is about 56% (Jackson 1987). The trees are deciduous, dropping leaves in the winter. Young leaves appear about the end of February and leafing is complete by early April making April to May the best time of the year for the production of high-quality fodder (Jackson 1987). Although the material has no known told compounds, feeding green leaves sometimes causes digestive disorders which can be prevented by making silage (Jackson 1987). Sissoo silage contained 14% crude protein and 30% crude fiber (Anon. 1952).

BIOMASS PRODUCTION: A study of 40 natural riverine sites showed that growth for 20, 30 and 50-year-old stands was 5, 7 and 7 m3/ha/year (CSIR 1976). A 10-year-old irrigated plantation in Peshawar, Pakistan, spaced at 2 x 2, 3 x 3 and 4 x 4 m produced a total wet weight biomass (main stem, branches, leaves and roots) of 510, 231 and 244 , tonnes/ha, respectively (Sheikh 1988a). In Nepal a 9.5-year-old stand thinned to 867 trees/ha at 6.5 years produced an annual increment of 18.1 M3 (Jackson 1987). A permanent water table 7 m below the surface made the site very favorable. Species trials have indicated that total biomass yields for sissoo are usually lower than that of other species (NAS 1983, Sheikh and Haq 1982, Sheikh 1988b). Sissoo should therefore be used in areas where a high-value timber market is available, or on sites unfavorable for other species.

SEED TREATMENT. Seeds (50,000/kg) remain viable for only a few months when exposed to air, but can be stored for up to 4 years in sealed containers (Jackson 1987). It is not necessary to extract seeds from pods, which can be broken into one-seeded segments and sown. Seeds should be soaked in water for 48 hours before sowing, and 60-80% germination can be expected in 1-3 weeks (Jackson 1987).

ESTABLISHMENT. Stump cuttings are commonly used for establishment. Plants are grown for 6 months to 1 year in beds, pulled up carefully and cut to leave 5- 10 cm of stem and 20-25 cm of root. Stumps thicker than 2.5 cm and thinner than 1.5 cm in diameter are rejected in Pakistan, although in Nepal stumps average 1 cm in diameter at the root collar (Jackson 1987).

Container-grown seedlings also are used, but outplanting survival averages only 50%. Regular root pruning is necessary in the nursery, as seedlings develop strong taproots. Direct seeding has been a common practice in taungya plantings in India. Rows are planted 3 m apart and saplings are thinned to a 1 m spacing within rows after one year. It is also possible to raise plants from stem cuttings. The age of the tree and time of planting are very important. Rooting success of hardwood cuttings from 1-year-old and 4-year-old trees ranged from 34-73% and 18-38%, respectively. Wood cuttings planted in May and June failed completely, while those planted in August achieved up to 20% success (Vidaeovic 1968); May and June are hot and dry and monsoons occur in August in the study area. Pain and Roy (1981) reported 100, 80 and 60% rooting success with IBA, NAA and IPA treatment for 30 seconds, respectively, when summer planted. There has been some success with tissue culture (Jackson 1987).

SILVICULTURE: At spacings of 4 x 4 m, 3 x 3 m and 2 x 2 m, height and diameter after 6 years were 8.4 m and 11.3 cm, 8.7 m and 10.1 cm, and 8.7 m and 8.6 cm, respectively (Sheikh 1984). Differences were not significant, but the 2 x 2 m spacings produced trees with fewer branches and more fuelwood. After 9 years, height and DBH for the three spacings were 15.1 m and 18.9 cm, 13.4 and 15.6 cm, and 13.9 m and 14.2 cm.

Thorough weeding is important during the first 2-3 years. In a trial at Adabhar, Nepal, mean height at 18 months was 3.8 m in fully cultivated plots and 1.3 m when weeding was confined to a 50 cm diameter circle around the plants (Jackson 1987). Protection against browsing animals and fire also is essential if the plant is to become a tree. Irrigation is very important for establishment of sissoo in and and even semiarid areas; it is through canal irrigation that the species has spread throughout much of the Indus valley. Sissoo should be able to tap sub-soil water within a couple of years if irrigated properly (Anon. 1952). Shallow and frequent irrigation or constant flooding induces superficial root formation.

Fertilization with various combinations and amounts of NPK did not show significant effects on DBH or height over 5-6 years on a rich soil (Sheikh and Cheema 1986). Phosphate would normally be expected to promote early growth on poor soils.

PROVENANCES: Selections for fast growth and tree form have been made in Pakistan and India and experimental seed orchards established. In a trial at Adabhar, Nepal relatively small differences in height growth in two years were observed for seven Nepal provenances, but two Pakistan provenances showed inferior growth to the Nepalese provenances.

OTHER USES: Some ethnic groups in Cameroon are said to relish eating fresh young leaves of sissoo (Anon. 1987). Sissoo is a desirable shade tree in tropical and subtropical regions. Many medicinal uses for its fresh leaves, dried bark, and wood raspings are reported from its native region. Sissoo is reported to be a stimulant used in folk medicine and remedies (Nadkarni 1954). Its habit of developing root suckers and runners make it useful for erosion control in gullies (NAS 1983).

PESTS AND DISEASES: Plecoptera reflexa, a leaf defoliator, Dichmeria eridantis, a leaf roller, Stromartium barbatum, a wood borer, and Sinoxylon anale and Lyctus africanus, powder post beetles, have been reported as having caused considerable damage. The fungus, Ganoderma lucidum, which causes root and butt rot, is common. Fusarium solani and Polyporus gilvus cause similar diseases. Sissoo suffers minor damage from two foliage rusts and a powdery mildew (Jackson 1987).

References

Anon. 1952. Ile wealth of India. Raw Materials. Vol. HI. D- E. CSM New Delhi.

Anon. 1987. Study on Dalbergia sissoo in North Cameroon. Ctr. for Forestry Res. Rep. of Cameroon. No. 23.

CSIR (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research). 1976.The Wealth of India. Vols. 10, 11. New Delhi.

Jackson, J.Y- 1987. Manual of Afforestation in Nepal. Nepal UK For. Res. Project, Department of Forest, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Pain, S.K. and B.K. Roy. 1981. A comparative study of the root forniing effect of IPA, IBA, and NAA on stem cuttings of Dalbergia sissoo. Ind. For. 107(3):151-158.

Nadkarni K.M. 1954. Indian materia medico. 3rd edition. 432 pages.

NAS (National Academy of Science). 1983. Firewood crops: shrub and tree species for energy production. Vol. 11. NAS Press, Washington, D.C.

Sheikh, M.I. 1984. Effect of spacing on growth of Dalbergia sissoo. Tech. Notes 1-55; Tech. Note 41:82-83.

Sheikh, M.I. 1988a. Biomass production from shisham plantation at different spacings. For. Res. Serv. Tech. Note 62:1.

Sheikh, M.I. 1988b. Comparative growth of four species under irrigated conditions. For. Res. Serv. Tech. Note 61:2.

Sheikh, M.I. and Afzal Cheema. 1986. Effect of fertilizer on the rate of growth of forest trees. Final Tech. Rep. For. Inst. PSR:119.

Sheikh, M.I. and R. Haq. 1982. Performance of poplars and other species in conjunction with agricultural crops. Pak. lour. For. 32(2):72.

Vidacovic, M. 1968. Propagation of shisham (Dalbergia sissoo) by cuttings. UNDP-FAO. Pak. For. Res. and Training Program. Rep. No. 3.

Written by Dr. M.I. Sheikh, Dirctor General, Pakistan Forest Institute, Peshawar, Pakistan.

A publication of the Forest, Farm, and Community Tree Network (FACT Net)