Winrock Issues Guidance for Monitoring & Evaluation During COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic is forcing development projects to adjust how they collect data from project beneficiaries with little in-person contact. In response, Winrock International’s Analytics, Gender, Inclusion, Learning and Evaluation (AGILE) unit created this guidance document to help Winrock project teams around the world assess the prospects, approaches and considerations for monitoring and evaluation activities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic is forcing development projects to adjust how they collect data from project beneficiaries with little in-person contact. In response, Winrock International’s Analytics, Gender, Inclusion, Learning and Evaluation (AGILE) unit created this guidance document to help Winrock project teams around the world assess the prospects, approaches and considerations for monitoring and evaluation activities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Winrock is publishing the document as a learning tool for any other organizations seeking to implement monitoring, evaluation, research and learning (MERL) best practices during the pandemic. Neither prescriptive nor specific, the document covers: (1) general guidance, (2) guidance for routine data collection, (3) guidance for remote data collection for evaluations, surveys, and studies, (4) ideas for continuing and reprioritizing MERL activities, and (5) what to do next, when the situation resumes.

GENERAL GUIDANCE

Overarching Direction

First and foremost, it is critical that you follow all host government, donor, and Winrock guidance and safety measures as they apply to your specific project.

Follow the Do No Harm principle. It is imperative that projects do not intentionally or unintentionally create additional risks to staff, partners, beneficiaries and the communities where projects work, but instead that they prioritize the well-being of all. Projects need to carefully and constantly consider their actions and interventions so that they neither cause potential harm nor exacerbate tensions, conflicts, vulnerabilities, etc.

Reach out to the AGILE team for specific guidance.

Communication

Maintain close communication with the donor, especially if you are changing existing plans or if there are possible data quality issues that will arise from MERL in the current situation. When communicating with the donor, be sure to propose mitigation measures for any potential problems that you are sharing with them.

Maintain communication within the project, ensuring that MERL findings are used for adaptive management in a timely fashion.

Communicate any planned activities with local authorities and/or community actors and respond to their feedback and concerns.

Communicate any changes and delays to beneficiaries, as necessary.

Flexibility

Be prepared for a rapidly and continually changing environment; use the outputs of MERL activities to adapt and plan accordingly.

Assess critical vs. non-critical MERL activities and balance risks against program necessity.

Consider delaying MERL activities that may be subject to significant bias in the current climate (more on sources of bias below).

GUIDANCE FOR ROUTINE DATA COLLECTION

Where program activities are ongoing, it is important to continue monitoring the progress of those activities. This may require adapting existing monitoring practices to the current realities of what is possible, which may require remote monitoring.

It is critical that projects have the documentation to demonstrate that project activities occurred and who benefited from them, in accordance with the donor’s requirements. In many cases, projects already have data collection forms that they use to track these activities. The main changes that might be required are (1) who fills in the forms and (2) how the forms are shared with the project MERL team.

Remote Monitoring

The specifics of the remote monitoring approach depend on the nature of the activity. Some examples include:

Training – the trainers still need to fill out a form, take a picture of the form and send it to the MERL team via email or MMS, keep and send the hard copy form afterward, when possible.

Distribution – the team in charge of the distribution has to fill out a form, take a picture, send it to the MERL team, and keep and send a hard copy afterward, when possible.

Sensitization campaign – projects need to work with the media outlet to estimate and document the outreach. If you use information and communication technology (ICT) like SMS, interactive voice response (IVR), or voice messages, work with the ICT companies to get the records.

If an activity is being facilitated remotely instead of in person, the remote facilitator must still fill out a form that includes information that can be used to verify the activity/participation. Telephone numbers are most commonly used. Even if not all participants have a phone number, having several numbers would allow verification as people usually know each other in the communities/groups. Pictures or videos are acceptable but are usually more difficult to collect and send. Another option is to record training/activities that are hosted online (or the first five minutes) to document the number of attendees.

Revised Approach

If projects revise their implementation strategies and introduce new activities, the MERL team should be proactive and assess the need to design/revise the MERL approach accordingly. Technical and MERL staff need to work collaboratively to ensure that all shifts in programming are reflected in updated MERL approaches. Any new or revised forms for activity monitoring should be ready when the activities are implemented. Those responsible for filling in the forms, taking the pictures and submitting them should be trained — remotely if necessary — and have a complete understanding of the purpose, process, and tools for carrying out the routine data collection. It is very difficult to try to collect data on an activity that already happened, and it would be even more difficult given the current situation.

Data Quality

Data quality remains of utmost importance. Ensure that the forms are sent and processed in a timely fashion so that you have numbers as accurate as possible to report, that the forms are completely filled out and are not missing any critical data, that you send and store the data in a secure way, with the level of security proportional to how sensitive the information is. Projects should conduct data quality reviews promptly via methods such as calling the telephone numbers on the forms, checking form completeness, assessing their timeliness, etc. You can conduct data quality reviews in a more extensive way when normal operations resume.

GUIDANCE FOR REMOTE DATA COLLECTION FOR EVALUATIONS, SURVEYS, ETC.

As the response to the coronavirus pandemic continues to change, donors will likely request a shift to remote data collection-based surveys for evaluations, outcome surveys and studies. Contrary to the routine monitoring mentioned above, surveys are collected from a sample of a population, adding a layer of difficulty to maintain scientific standards.

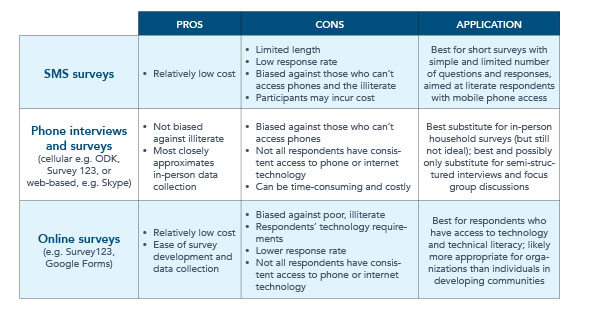

The following is a list of guidelines to consider when shifting from in-person data collection methods [such as focus group discussions (FGDs), key informant interviews (KIIs) and household- or individual-level survey interviews] to remote data collection methods such as those outlined in the table below.

In general, remote data collection is not ideal, particularly where infrastructure means that not all possible respondents can be included remotely. The tips below are offered to try to identify and mitigate some of the problems that can come up, many of which are applicable to fielding online surveys as well as to phone interviews. Think creatively and ask for help mitigating the effect of travel restrictions on your data collection activities.

Focus Group Discussions: It will likely be impossible to effectively conduct FGDs remotely. Plan to switch to individual interviews, but remember that FGDs and KIIs are not interchangeable. Be aware that this will mean losing out on group interactions and other specific benefits of FGDs. Be sure to think through what using only individual interviews, without visual cues from respondents’ body language, means for your findings and recommendations.

Document decisions: If you plan to work with multiple types of respondents to answer multiple research questions, think about which types might be more difficult or impossible to reach through remote data collection. How will this affect what questions you can answer and the quality of the answers you do get? Clearly documenting your decision-making processes will help you address questions about possible limitations. When there are trade-offs to be made, documenting that you are aware of these trade-offs and have made them deliberately will help you ensure that you are making the best possible decisions within constraints.

Rapport: It is more difficult to establish rapport when collecting data remotely than in person. Be sure to build in time to chat with your respondent and put them at ease at the beginning and end of your conversation. It is very important to structure your interview guides to facilitate openness and sharing. In general, start with easy questions to get your respondent comfortable speaking, and move on to more difficult or complex questions. Train your data collectors on how to establish rapport with respondents remotely. Consider doing role plays so that collectors can practice establishing a connection quickly and following the interview guide properly without sounding as if they are reading a script. Keep in mind that SMS and online surveys do not allow opportunities for building rapport with respondents.

Track respondents: Be sure to carefully track response rates. Have a protocol for how many times and how you will try to reach individual respondents. Keep good records of who you try to contact, who you successfully reach, and how these groups may vary by type of respondent. For example, if you are interested in speaking with both government officials and project participants, you may have an easier time reaching government officials, who may have more access to communication technology.

Potential bias: Think through whether different groups of respondents, in addition to having varying levels of access to technology for remote data collection, have different levels of comfort in speaking via phone or writing their responses. These differences might systematically bias certain groups’ responses, just as different response rates might bias your results systematically. For example, it will be easier to reach urban populations and more affluent people with smartphones and other technology that will enable remote data collection. This method will lead to fewer responses from rural and low-income people, as well as from women who may have less access to technology. If the benefits of conducting the survey/evaluation/activity outweigh any potential bias, be sure to address sources of bias in the methodology and/or discussion sections of the report. Also consider using methods of correcting for bias when analyzing the data.

Increase Sample Size: Whether you are sampling your respondents randomly or non-randomly, consider oversampling. You will very likely have lower response rates, as discussed above, and need to ensure that all types of respondents are included in the final sample at sufficient levels. What is “sufficient” will depend on the goals of the research and what type of sampling you are doing.

Document possible effects: Carefully consider and document the potential effects of shifting to remote data collection. This will help identify possible mitigation methods throughout the research process. For example, to mitigate the risk of non-response bias, you might perform a desk review to understand non-response rates in your project’s context and data-collection approach, then oversample proportionately to correct for non-response. Be sure to keep in mind the mode of data collection during data analysis and include any possible effects in a limitations section of the final report.

Informed consent: Be sure to document informed consent remotely. Ensure that participants know that their participation is optional and that if they are concerned about COVID-19 transmission resulting from the survey/evaluation/activity, then they do not have to participate (for this or any other reason).

Budget: Consider the effect of remote data collection on the budget. For example, there may be additional workload associated with developing an online survey, but that might be balanced out by reductions in travel costs and LOE for carrying out the survey.

Contact method: Determine what medium (WhatsApp, SMS, etc.) is best to reach your specific respondents, or make multiple options available.

Shorten data collection instruments: If possible, consider using an abbreviated survey or interview guide tailored for remote data collection. Respondents may fatigue more quickly with remote data collection methods compared to in-person data collection, so avoid extraneous questions that are not critical to the core purpose of the survey. This may require donor approval.

CONTINUING AND REPRIORITIZING MERL ACTIVITIES

Consider the following MERL activities that can continue or be scaled up:

Report writing in accordance with the donor requirements. Document possible effects COVID-19 had on data collection and outcomes.

Remote monitoring of current and revised or new activities, as mentioned above.

Remote data quality reviews; it is a good time to go into the data, clean, and assess its consistency, validity, reliability, integrity, etc.

Remote pause-and-reflect/learning sessions, to gather and document learnings that might be applicable to the current situation.

Preparation for upcoming surveys, learning studies and evaluations, such as designing and refining survey and evaluation protocols, working on the procurement files, etc.

Setting up or improving databases; this is a good opportunity since you will likely have less data coming in.

Production or revision of training materials for grantees/partners based on lessons learned, to ensure they provide us with high-quality data.

GESI activities such as gender audits/assessments of staff and partners, so that the next workplans and interventions better integrate GESI, etc.

Create project dashboards connected to project databases in order to visualize progress.

WHAT TO DO WHEN ACCESS TO BENEFICIARIES RESUMES

Assess the effects of COVID-19 on your beneficiaries and share the findings with staff, partners and the donor. Reach out for specific guidance on different methods to conduct and integrate that assessment into your activities. Options include adding questions to an already planned survey or evaluation; creating a quantitative or qualitative survey if you have an idea of the types of effects; or adding complex monitoring approaches, such as outcome harvesting, which are more relevant to study not only expected but unexpected effects.

Ascertain the extent to which your theory of change or development assumptions are still relevant and valid using the findings from the above.

Adapt by organizing pause-and-reflect sessions with staff, partners and the donor to discuss these findings, revise your theory of change or development assumptions, and integrate the resulting strategies into your work plan.