Enterolobium cyclocarpum: The Ear Pod Tree for Pasture, Fodder, and Wood

NFTA 90-05, November 1990

A quick guide to useful nitrogen fixing trees from around the world

Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. is one of the largest trees in the dry forest formation of Mexico and Central America, reaching up to 3 m diameter and 40 m in height with a huge spreading crown. It is a conspicuous and well-known tree in its native range. Large crowned trees scattered in pastures are a common sight and a distinctive feature of the landscape in many parts of Central America. Such is its fame that Enterolobium has been adopted as the national tree of Costa Rica. The province of Guanacaste in Costa Rica is named after Enterolobium which occurs abundantly in that area.

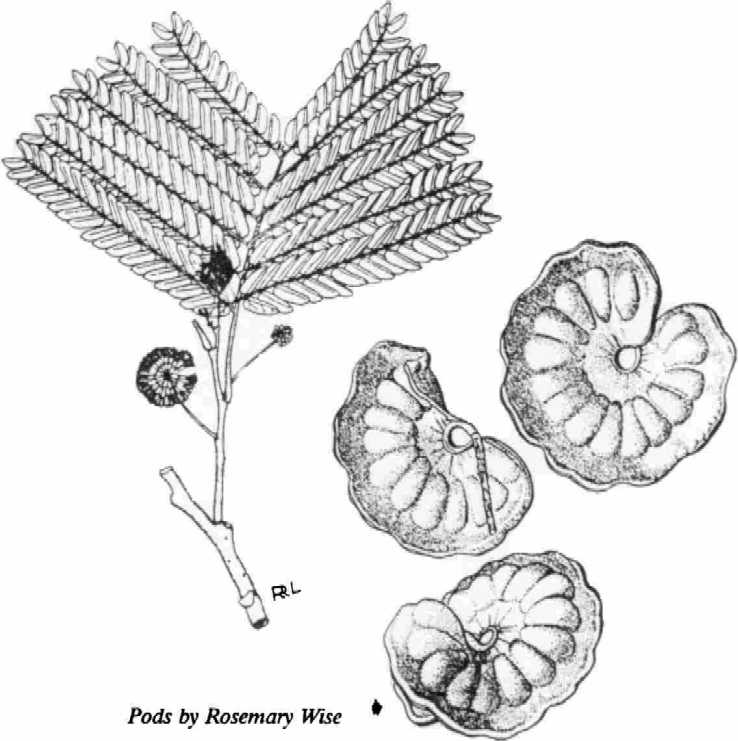

Enterolobium cyclocarpum is also well-known for its distinctive, thickened, contorted, indehiscent pods which resemble an ear in form. Most of the common names for Enterolobium refer to this resemblance, including ear fruit, ear pod, orejoni (from Spanish oreja, an ear) and guanacaste (conacaste, a Nahuatl derivation signifying ear tree).

Enterolobium cyclocarpum is also well-known for its distinctive, thickened, contorted, indehiscent pods which resemble an ear in form. Most of the common names for Enterolobium refer to this resemblance, including ear fruit, ear pod, orejoni (from Spanish oreja, an ear) and guanacaste (conacaste, a Nahuatl derivation signifying ear tree).

Botany

The nitrogen fixing tree Enterolobium cyclocarpum belongs to the subfamily Mimosoideae of the Leguminosae and is placed in the tribe Ingeae. The genus Enterolobium is closely related to Albizia and Samanea and is probably only maintained as a separate genus due to its widespread cultivation. Enterolobium contains only five species, all from Central and South America, and only E. cyclocarpum is widely cultivated. Closely related species, such as E. schoinburgkii Benth., remain untested to date.

Enterolobium leaves are bipinnately compound with opposite leaflets. Small white flowers occur in compact round heads. In Central America E. cyclocarpum is sometimes confused with Albizia niopoides (Guanacaste blanco) due to similarity in tree form but may be readily distinguished by the different bark which is pale golden yellow in A. niopoides

Ecology

Enterolobium cyclocarpum occurs from latitude 23oN in central Mexico, south through Central America, to 7oN in northern South America. It has been widely introduced throughout the tropics where it is cultivated mainly as a roadside or garden tree. In its native range, Enterolobium occurs in a wide range of different forest types from tropical, dry deciduous forest to tropical moist forest. It becomes a climax tree only in the dry forest, being restricted to disturbed areas in wetter forest types. Enterolobium cyclocarpum is a lowland species occurring from sea level to 1200 m elevation and has only very limited tolerance of frost.

Annual rainfall varies between 750-2500 mm through most of its native range with a dry season that lasts 1-7 months. Trees are generally deciduous, losing their leaves during the dry season and flushing out again about two months before the onset of the rainy season. Flowering starts while the trees are leafless (March- April in Central America), and the pods take a year to mature, ripening in April-May.

Uses

The wide spreading canopy of a mature Enterolobium makes it an ideal shade tree, whether for livestock in pasture lands, for perennial crops such as coffee, or in roadside and urban plantings. Its value to livestock is further enhanced by production of large quantities of highly palatable and nutritious pods containing a sugary dry pulp. Pods are generally shed at the end of the dry season in Central America when livestock feed is particularly short. Pods fall from the trees gradually over a period of two months thus spreading the availability of pods for livestock. Data from Puerto Rico suggests that pod production may be delayed as much as 25 years after planting. The foliage is also palatable, though to a lesser extent than the pods, which results in high mortality of natural regeneration in pasture lands and may explain why the tree occurs naturally only as scattered individuals.

Enterolobium heartwood is reddish-brown, coarse- textured and moderately durable, with a straight interlocking grain and an appearance somewhat similar to walnut. Specific gravity is variable, ranging from 0.4- 0.6. The wood is resistant to attack by dry-wood termites and Lyctus, and can be used in house construction as well as for nonstructural interior elements including panelling. The white sapwood, by contrast, is highly susceptible to insect attack. Enterolobium wood may also be used for boat-building because of its durability in water; it has been used in the past for water-troughs and dug-out canoes. The dust from sawmilling can produce allergic reactions in workers.

Other uses include food (the immature pods as a cooked vegetable, or the seeds toasted and ground), soap-making (using tannins from the pods and bark), and medicinal use of bark extracts against colds and bronchitis. The ability of Enterolobium to fix nitrogen, and to resprout vigorously when coppiced, suggest it could also have a role in alley-cropping systems as a hedgerow species, though this is an area requiring further research.

Silviculture

Enterolobium is a light-demanding species at all stages in its development. It is susceptible to weed competition during early growth. Enterolobium resprouts vigorously after coppicing or lopping; indeed, it is difficult to kill Enterolobium by girdling because of its tendency to resprout below the girdle line. Little information is available, however, on its response to repeated cutting. With no silviculture intervention it usually occurs as a single, large, open-grown tree, though pruning can improve the length and form of the bole.

Enterolobium can tolerate a wide range of soil types, from alkaline and calcareous to somewhat acidic (pH as – low as 5), provided that aluminum saturation is not a problem. Best growth is on deep, medium-textured soils but sandy and clay soils also allow good development provided drainage is unimpeded. The trees will not thrive on sites prone to waterlogging.

Propagation

The combination of large nutritious pods and seeds with hard coats is ideal for seed dispersal of Enterolobium by animals. Seeds are most easily collected by waiting for pods to fall. An adult tree produces an average of 2000 pods, each with 10-16 seeds (900-1200/kg). Trees produce seed crops in most years in Central America. Seed extraction from the indehiscent pods is usually carried out by manual threshing, milling or maceration of the pods followed by winnowing and screening

Enterolobium seed is naturally scarified by passage through the gut of large herbivores. It is likely that the original consumers of Enterolobium pods are now extinct and their role as seed dispersal agents has been assumed by horses and cattle. Collected seed requires pretreatment before sowing to allow water to penetrate the seed coat. Manual scarification is effective, as is treatment with hot water or concentrated sulfuric acid. A suitable hot water treatment is a brief (30 second) soak in water close to boiling point, followed by 24 hours in water at room temperature. Enterolobium seeds remain viable for several years under cool, dry conditions and can be easily stored under normal conditions.

Seed supplies are currently dependent on collections from natural populations in Latin America and scattered cultivated trees in areas where Enterolobium has been introduced. Most early introductions of E. cyclocarpum were undocumented, casual and collected from a narrow genetic base. A broader range of representative germplasm should be tested to evaluate the potential of the species. Seed is available from OFI and NFTA for the establishment of field trials.

The seed should be sown 1-2 cm deep with the micropyle pointing downwards; the emerging root is not strongly geotropic and may come up out of the soil if the seed is planted upside down. Early seedling growth is rapid and vigorous. This early advantage over smaller-seeded species can continue several months after outplanting, but thereafter growth rate, though still vigorous, is no longer exceptional relative to other fast growing species.

Pests and Diseases

Enterolobium has no serious or widespread disease and insect problems, although attack by a Fusarium fungus, with associated damage by wood-boring insects, can cause affected limbs to fall from mature trees. Branches may also be broken off by storm damage. Both factors reduce the desirability of Enterolobium for urban and roadside planting. Although no bruchid seed predators are found on E. cyclocarpum, the green pods are often preyed upon by parrots and fruiting may be further disrupted by the gall forming moth Asphondylia enterolobii.

Principal References

Echenique-Manrique, R. and R-A. Plumptre. 1990. A guide to the use of Mexican and Belizean timbers. Tropical Forestry Paper 20. Oxford Forestry Institute, LTK. 175 p.

Francis, J.K. 1988. Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. Guanacaste, Earpod-tree. Leguminosae. Legume Family. USDA Forest Service. Southern Forest Experiment Station. SO-ITF-SM-15.

Janzen, D.H. 1983. Enterolobium cyclocarpum. In D.H. Janzen (ed.), Costa Rican Natural History. Univ. Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. 816 p.

Little, E.L., R.O. Woodbury, and F.H. Wadsworth. 1974. Trees of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, Vol. 2. USDA Agric. Handbook No. 449. p. 258-259.

Standley, P.C. and J.A. Steyermark. 1946. Enterolobium In Flora of Guatemala. Fieldiana: Botany 24(V):32-34.

Written by C.E. Hughes and J.L. Stewart, Oxford Forestry Institute, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3RB, UK

A publication of the Forest, Farm, and Community Tree Network (FACT Net)