Difficult Sites Are Home to Casuarina

NFTA 85-03, December 1985

A quick guide to useful nitrogen fixing trees from around the world

Sand, sun and salt spray are part of home to the Casuarina spp. that thrive on beaches from the tropics to temperate zones. The ability to tolerate diverse and difficult niches such as seashores characterize the genus. Casuarinas also have been grown on limestone quarries and infertile tin mine tailings.

C. equisetifolia, which occurs naturally on coastlines from India to Australia, is the most widely used species. A 3000 km shelterbelt was built mainly with C. equisetifolia along the People’s Republic of China’s southern coast to stop encroachment of sand dunes and to decrease strong winds. A similar shelterbelt in Taiwan reduced downwind salt deposition by 60 percent (Koki, 1978).

In Egypt, C. glauca and C. cunninghamiana shelterbelts protect farms, highways and irrigation canals from clogging by sandstorms.

Casuarina has been called the best firewood in the world. Its wood is very dense, splits easily, burns when green, has low ash content and makes excellent charcoal (NRC, 1984). It is the main plantation species in peninsular India, where 7-15 year rotations yield 100-200 tons of fuelwood per ha (NRC, 1984) and even the roots are sometimes harvested for charcoal. Yields of 7.5- year-old stands in Florida were up to 17 dry t/ha/yr (Rockwood, et al.; 1985).

In Thailand, hybrids of C. equisetifolia and C. cunninghamiana grow on heavy acid soils and are harvested five years after planting for posts, firewood and other products. Villagers in southern China gather four tons/ha/yr of Casuarina litter from shelter- belts and use it for domestic fuel (NRC, 1984).

Most Casuarina wood is hard, heavy and difficult to saw. It also tends to split, crack and warp as it dries. However, the wood is used for fencing, pilings, beams, rafters, ship masts, scaffolding, flooring, particle board, roof shingles and pulp.

C. oligodon shades coffee trees and is a fallow-improvement crop in Papua Ne–, Guinea. Soil samples collected after five years of such a fallow show substantial increases in soil nitrogen and organic matter (NRC, 1984).

Casuarina roots are modulated by the nitrogen-fixing actinomycete, Frankia. Annual nitrogen fixing rates for established

C. equisetifolia stands has been estimated near 60 kg/ha (Dommergues, 1963). Inoculating seedlings with Frankia and mycorrhizal fungi promotes faster growth and survival, and seedlings are ready for planting in six months or less.

Suitable growing conditions for C. equisetifolia in the tropics and subtropics include: temperatures of 10-300 C with no frost, 200 to 5000 mm annual rainfall, 6-8 month dry season, sea level to 1500 m, and sandy, calcareous soils. C. cunninghamiana tolerates about 50 light frosts annually and survives periodic inundation in fresh water. C. glauca survives tidal inundation and is very drought tolerant. C. oligodon grows well in humid highlands up to 2500 meters above sea level, and C,, iunghuhniana grows in drier highlands up to 3000 meters.

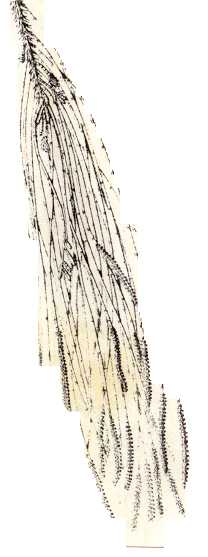

Casuarinas normally are propagated by seeds. C. equisetifolia produces seed prolifically by the age of 5 years. Most species have separate male and female trees, but some species have both flowers on one tree, and C. equisetifolia is reported as fitting into both of these categories. Seeds of different species vary greatly in size. C. equisetifolia has between 300,000 to 450,000 seeds/lb. Germination generally takes 2-3 weeks. Germination rates for C. equisetifolia range from 75 percent for fresh seed

to 30 and 40 percent for stored seeds.

A male clone presumed to be a hybrid of C. equisetifolia and C. junghuhniana is reproduced by young, short cuttings in Thailand and India. Vegetative propagation efforts with C. equisetifolia have not been very successful, although rooting of properly treated young lateral shoots has been as high as 90 percent (Somasundaram and Jagadees, 1977). Trees coppice poorly or not at all. The root-derived shoots of some species allow for a type of “coppice” management, however (NRC, 1984).

Pest problems on casuarinas have been minor. Root rot in Florida and a blister disease in India have occurred. Many species survive fires well, but even light fires kill C. equisetifolia.

Some casuarinas can become pests. C. glauca’s vigorous root suckering has created problems in Hawaiian pastures and in Florida, where some counties have banned its planting. Additionally, leaf litter of some species may be toxic to some plants and increase soil acidity or salinity.

Abstracts have been made by author D.L. Rockwood from documents or observations by the authors cited.

A publication of the Forest, Farm, and Community Tree Network (FACT Net)