James Yekeh’s three takeaways from Winrock’s 10+ years of building successful long-term partnerships to combat child labor in Liberia

Winrock International has implemented over 14 child labor prevention projects in more than 34 countries since 2002, impacting and reaching over 134,000 households, and effectively removing and preventing almost 75,000 children from exploitive and hazardous child labor. Winrock’s integrated development approaches address livelihoods, food security, education, community engagement, and leadership and capacity development. On World Day Against Child Labor 2024, we asked Monrovia-based James Yekeh, project director of the U.S. Department of Labor-funded ATLAS project in Liberia, to reflect on his experience leading Winrock’s child labor portfolio in Liberia over the past 10 years. He outlined three key approaches that have led to successful partnerships with government and communities to prevent child labor.

1. Strong and consistent stakeholder engagement builds momentum for sustainable success.

Currently I work on ATLAS, which is short for Attaining Lasting Change for Better Enforcement of Labor and Criminal Law to address Child Labor, Forced Labor and Human Trafficking ─ but it’s only the latest in a series of Winrock-led projects over the past 10 years, all of which involved close collaboration with Liberia’s government to prevent child labor. ATLAS is a global initiative that previously worked in Thailand, Argentina and Paraguay, in addition to Liberia, to strengthen enforcement of labor and criminal law to address child labor, forced labor and trafficking in persons. ATLAS works collaboratively with host governments to bolster the legal and criminal frameworks surrounding these issues, to improve enforcement of laws, and to facilitate coordination among law enforcement, including police, labor inspectors, prosecutors and judges.

I’m on ATLAS, today, but my work with Winrock in Liberia began in 2013 with the USDOL-funded Actions to Reduce Child Labor project, focused on rubber plantations. That initiative targeted children in child labor or at risk of child labor by providing new education opportunities for them, combined with expanded training, livelihoods and employment opportunities for parents. Ultimately, the passage of key legislation to eliminate child labor in Liberia, which was developed by the government with support from ATLAS, has roots that trace back to those initial Winrock-led projects, so I want to cover some of that earlier work.

At the start of the four-year (2012-2017) ARCH project, Winrock worked hard to develop a partnership with Liberia’s Ministry of Education to help improve children’s access to educational opportunities. We also collaborated closely with the Liberian Ministry of Labor on one of their main goals: establishing a National Steering Committee. The committee is responsible for coordinating child labor elimination efforts, and it had the huge responsibility of developing Liberia’s National Action Plan on the Elimination of Child Labor, or NAP. The NAP aims to reduce child labor and the worst forms of child labor by 50% by 2030 by increasing public awareness, strengthening legal and institutional frameworks, and expanding social services and protection for children in vulnerable households.

The ARCH project focused on rubber farming, which is grueling and dangerous work for children. Of course, work on rubber farms also keeps children out of school and limits their chances of having a normal childhood. Child labor is a big problem on rubber farms for a few reasons, including poverty levels, worker quotas, the high costs of paying for adult labor, limited access to education and lack of enforcement. To give an idea of the scope of the issue, data from USDOL’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs indicates that a little more than 30% of children in Liberia aged 5-14 are working at various jobs, and more than 28% are both working and attending school.

The ARCH project worked with the government to address those challenges, and these efforts built the foundation for future progress.

We worked with communities to enroll more than 10,100 children and youth in formal education programs, accelerated learning programs, model farms, agriculture clubs and community skills training. These and other programs offered alternatives to keep school-aged kids away from dangerous work on the rubber plantations and elsewhere. Another major ARCH activity focused on livelihood opportunities for parents, targeting households most vulnerable to child labor. Ultimately, we reached 3,700 households with support including information about vocational and job training; we also provided training to the leaders of 44 Parent Teacher Associations, helping them learn how to apply for small grants to bring education support programs into their own communities, for example.

I continued with Winrock on a later USDOL project called CLEAR II ─ short for Country Level Engagement and Assistance to Reduce Child Labor II. Under the Liberia portion of this global initiative, Winrock continued strengthening relationships with our government partners, especially with the Ministry of Labor and officials with the National Commission on Child Labor. Together we continued to work on the NAP. A big part of this involved supporting the commission in the development of new draft legislation to define and prevent child labor. Winrock worked with the commission’s steering committee, enabling us to meet, dialogue with and build further relationships with a wide range of key, national stakeholders across the country and across various institutions in support of legislative reforms. Our work with CLEAR II laid the foundation for development of Hazardous Work Lists that were approved later by the government, strengthening the system so the work could continue despite changes in administration and staff.

2. Good communication is key when working with government partners – and helps build trust.

I mentioned above our early collaboration with the National Commission on Child Labor.

That included frequently, clearly, and consistently communicating with our government partners from a range of other important agencies and entities, especially those with the knowledge and skills to drive legal reform in Liberia. We consulted often with experts from Liberia’s Judicial Institute at the Ministry of Justice, with local lawyers, and with officials from the Law Reform Commission; we also received inputs from nongovernmental partners including Lawyers Without Borders, international judges, local lawyers and other experts. This broad collaboration and dialogue enabled us to help the Legislative Reform Committee develop drafts lists defining Hazardous and Light Work that aligned with Liberia’s existing legislation on child labor. The LRC is a broad group comprising legal representatives from civil society organizations and from across government, including the Ministry of Labor, Ministry of Education and Ministry of Agriculture.

Under the ATLAS project, I am proud that we were able to witness the Ministry of Labor endorse Liberia’s first Hazardous and Light Work List regulations in 2022. Certain dangerous forms of child labor are now prohibited in Liberia including rubber tapping, sugarcane cleaning and harvesting, palm cutting, bush clearing and coal burning.

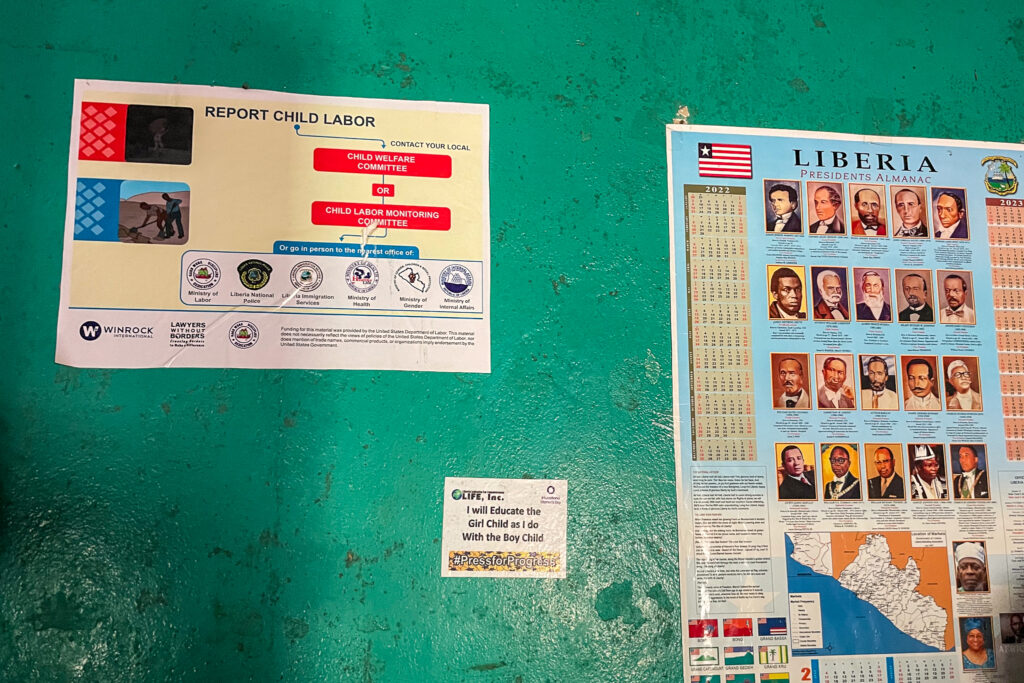

We also contributed to the drafting and revision of Liberia’s Child Labor Law, which is currently under review by the legislature and will be the first of its kind in Liberia if passed. Under ATLAS, Winrock provided trainings of trainers to officials from the Liberia National Police, Labor Inspectorate, and the Judicial Institute to improve their institutional capacity to address child labor.

Maintaining frequent and open communication with government partners helped Winrock’s project teams to build up trust. It enabled us to overcome any early reservations or doubts about the intent of our initiatives. We shared information frequently and openly with our government partners, demonstrating that we weren’t attempting to supplant the government’s efforts, but rather to support them. To assuage concerns, it also was crucial to ensure our government partners were engaged in each stage of the projects’ life cycles.

We gradually showed that Winrock’s aim was to enhance existing efforts, not to try to duplicate or supersede them.

3. Layering project activities onto existing government priorities enhances scope and sustainability.

Another key takeaway from working with all three of the USDOL projects (ARCH, CLEAR II and ATLAS) is the importance of working hand-in-hand with government and nongovernmental partners to ensure our efforts build upon and amplify the priorities and efforts of on-the-ground stakeholders. This helps in several ways. First, it contributes to building trust among individuals, agencies, and organizations with and through whom the projects operate. Second, it ensures that project activities are responsive to real needs and adapted to the local context. Finally, it contributes to sustainability by improving chances for project efforts to be perpetuated and expanded even after the projects come to a close.

These approaches have paid off with impact.

On the child labor side, building onto the Hazardous and Light Work Lists that we helped develop under CLEAR II: The lists are now attached to the national Decent Work Act as regulations and enforceable under law. The lists, developed through intensive coordination with international and local partners, are enhancing the smooth implementation of the NAP.

“We have for the first time as a nation come up with a list of what a child may do in terms of work and what a child should not do,” said former Labor Minister Charles H. Gibson, when he approved the lists.

After the lists were developed, we continued working with the Ministry of Labor to draft the country’s new Child Labor Law. It has since been finalized and submitted to the legislature for passage, which we hope will happen soon. As part of this work, Liberia also formally approved the International Labour Organization’s Convention No. 138 on the minimum age for work, which is another major step forward to protect children’s rights.

Today, as the ATLAS project winds down, I’m proud to say that Liberia’s government and civil society groups are collaborating, and very well positioned to build on the strong foundation laid to prevent and ultimately, end, child labor.

This gives vulnerable children in my country a chance at a better future.

Related Projects

Attaining Lasting Change for Better Enforcement of Labor and Criminal Law to Address Child Labor, Forced Labor and Human Trafficking (ATLAS)

The ATLAS project is a global initiative that has worked in four countries across Latin America, Africa, and Asia to strengthen enforcement of labor and criminal law to address child labor, forced labor and human trafficking. ATLAS works collaboratively with host governments to bolster the legal and criminal frameworks surrounding these issues, improve the enforcement…

Actions to Reduce Child Labor (ARCH)

Agriculture, particularly rubber, is an important contributor to the Liberian economy. A significant number of children are involved in the production of rubber due to household poverty, the high cost of adult labor, a lack of awareness about the hazards of work and limited access to education. Under these economic and social conditions, children perform…