Nitrogen Fixing Trees as Atoll Soil Builders

Agroforestry for the Pacific Technologies

A publication of the Agroforestry Information Service

April 1993, Number 4

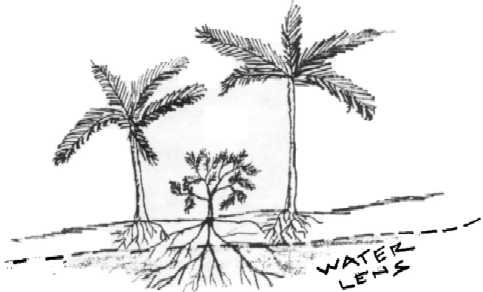

Atoll soils form from coral reefs that grew on the tops of subsiding volcanoes during various periods throughout the Pacific. Most of these soils are quite young in geologic terms and thus still similar in property to this coral parent material. Coralline soils are extremely nutrient deficient and highly alkaline. They are especially lacking in iron, potassium, and nitrogen. The so-called “soil” of atolls is really not soil at all since it is not made up of the usual components of soil: mineral sand, silt, and clay. Organic matter is all that really does distinguish most atoll soil from crushed coral.

Atoll farmers have always practiced mulching and composting to some degree. Most consider regular organic additions integral to any agricultural activity. Organic matter management–more on atolls than anywhere-is crucial to sustained food production. Organic matter holds nutrient ions, retains precious soil moisture, and buffers soil pH. In all soils, it builds and maintains good soil structure and provides essential plant nutrients. In atoll soil, it must also take the place of the missing clay component in providing nutrient cation exchange sites that are crucial to nutrient cycling processes.

Atoll farmers and gardeners typically make compost by piling-up rotting coconut shells/stems, household rubbish, and any green material they can rind. Most simply pile this material next to a target crop or tree as a mulch. The mulch then breaks down into compost over time. Many actually make compost first and then purposefully place it into garden trenches, holes, and taro pits as bedding material.

Although composting has always been part of the farming/gardening routine on atolls, one key ingredient is in very scarce supply-Fresh/green organic matter. As a result, mulch and compost are often spread too thinly to yield significant benefits. Compost formation is slowed drastically in piles with too high a dry: green (carbon:nitrogen) ratio of organic material.

Nitrogen-fixing trees are gaining recognition as promising atoll agroforest/garden additions and renewable sources of soil building organic matter. Anyone who knows a bit about the unique characteristics of these trees should not find this surprising.

Why Nitrogen Fixing Trees?

Nitrogen-fixing trees are able to “fix” or take up atmospheric nitrogen (N2) that is not available to other trees. They do this through a symbiotic relationship with certain bacteria-Rhizobia and Frankia–that form nodules in their roots. When the leaves and branches of these trees drop off or are harvested, this nitrogen becomes available to other plants or animals in the ecosystem.

Most nitrogen fixing trees are “pioneers” They establish easily on poor or degraded sites. These tenacious trees also grow rapidly, and produce large amounts of nitrogen-rich green foliage in some rather harsh environments.

Good mulch/compost producing nitrogen fixing trees for atolls also have the following characteristics:

- A high leaf nitrogen concentration

- A tolerance to excessive soil alkalinity A tolerance to excessive soil salinity

- A tolerance to excessive soil salinity

- A relatively high leaf tannin content: Many nitrogen fixing trees—such as Acacia spp.–contain tannins that slow the decomposition process. This is desireable in very humid, warm environments where the rapid break-down of organic matter prevents the build-up of a protective mulch or humus layer.

- Repeated and vigorous resprouting/regrowth after pruning: Many nitrogen fixing trees can be pruned or lopped as often as four times a year.

- Multi-purpose/multi -product: In addition to compost/fertilizer, many nitrogen fixing trees produce human-food, firewood/charcoal, pig or goat fodder, and timber or poles for construction.

Establishing and Integrating Nitrogen Fixing Trees

Because land-area is so scarce on atolls, it is especially important that selected trees be easily integrated into existing systems. Depending on local needs and preferences, a variety of tree planting and maintenance schemes are possible:

- Living fences and hedges protect crops from roaming animals and human foot-traffic. Trees are arranged densely or planted as fence posts.

- Windbreaks are single or multiple rows of trees planted on windward field boundaries. Windbreaks slow wind, reducing physical damage to crop’s and fruit trees. Placed on the windward side of atolls, they can also prevent salt-spray from reaching the interior and reduce coastal erosion.

- Hedgerows are dense single or multi-row plantings of trees within fields or among fruit tree plantations. Trees are arranged to minimize competition with the associated crop and pruned regularly to add compost or ‘green manure’ to the farming or garden system.

- Shade and support are attained quickly from fast growing nitrogen fixing trees. Shade provides protection from the hot, drying sun. Living, soil enriching support is quickly established for vine crops such as beans, potatoes, yams, and pepper.

- Home garden plantings of nitrogen fixing trees provide soil organic matter/ fertility while yielding edible fruits, leaves and flowers.

If a nitrogen fixing tree is being introduced to a site for the first time, seed or soil inoculation may be required. Seed inoculation is the process of coating seeds with the nitrogen fixing bacteria prior to planting. The inoculant is just a material that contains the bacteria. Inoculation is required when the proper bacteria is not already living in the soil where the tree will be planted. Most nitrogen fixing bacteria tolerate adverse environmental conditions such as soil alkalinity, to the same degree as the host tree. Inoculant for various nitrogen fixing tree species can be obtained from the NifTAL Center, 1000 Holomua Road, Paia, HI USA 96779.

Problems/Limitations with Nitrogen Fixing Trees

Weediness is a potential problem with nitrogen fixing trees, especially on small atolls with few native species. These trees, because of their nitrogen fixing capability, establish easily, grow rapidly, and tend produce large quantities of seed. Genetic improvement research has produced several varieties of many species such as Leucaena leucocephala. These improved varieties have less tendency to become weedy and are more compatible with crops. They are thus safer for introduction. All species introductions should be made with considerable caution.

On atolls, competition for precious groundwater is another possible problem where nitrogen fixing trees are planted into fields or fruit-tree plantations. Proper spacings and management techniques-such as periodic pruning-should reduce this problem.

Promising Nitrogen Fixing Trees for Atolls

The following nitrogen fixing trees are those that are proving themselves in harsh atoll conditions as good, renewable sources of nitrogen-rich mulch/compost material. All of these trees are tolerant to high soil pH. Those that are especially tolerant to soil salinity are noted for this. Each brief profile includes a list of outstanding characteristics and primary uses. All are easily propagated by seed and recommended seed-treatments are listed.

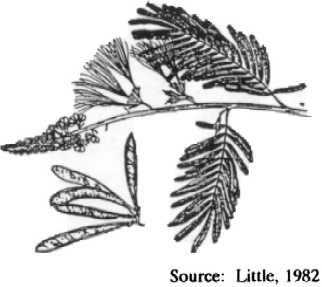

Acacia auriculiformis

|

|

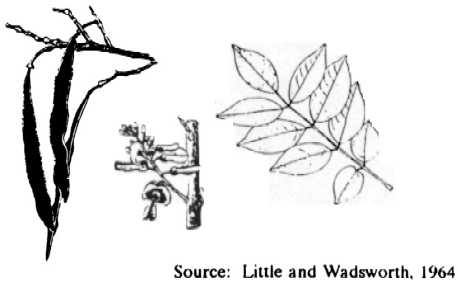

Albizzia lebbeck

|

|

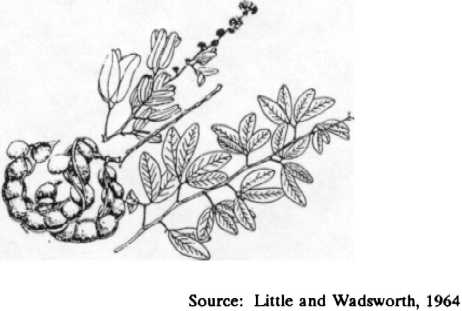

Calliandra calothyrsus

|

|

Casuarina equisetifolia

|

|

Gliricidia sepium

|

|

Pithecellobium dulce

|

|

Sesbania grandiflora

|

|

Sesbania sesban

|

|

Illustrations

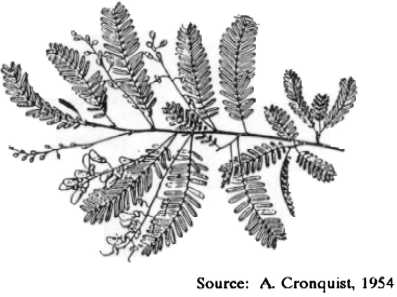

Cronquist A. 1954. “Galegeae”, in Flore du Congo Beige et du Ruanda-Urundi, Vol 5,p.77, Brussels.

Little E.L.Jr. 1982, Common Fuelwood Crops. Morgantown, West Virginia: Bower Communications Group.

Little E.L. Jr. and F.H. Wadsworth. 1964. Common Trees of Puerto Rico And the Virgin Islands. Ag. Hand. No. 249. USDA Forest Service, Washington D.C.

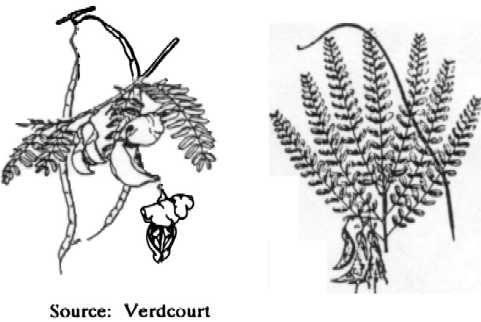

Verdcourt B. A manual of New Guinea legumes. Division of Botany, Papua New Guinea.

Written by K.R. Dalla Rosa, Program Director for the Pacific, NFTA, 1010 Holomua Road, Paia, Hawaii 96779 USA

A publication of the Forest, Farm, and Community Tree Network (FACT Net)

Winrock International

Email: forestry@msmail.winrock.org