Resource

Debt Bondage and the Tragedy of Commons – How Bondedness Leads to Overfishing and River Degradation in Barishal and Patuakhali

Note: The findings of this case study are based on four focus group discussions with fishers and their families in Char Memania village in Hizla, Barishal, and Char Dhadonia village in Dashmina, Patuakhali, in the South-central of Bangladesh.

Overfishing and River Degradation – A Perennial Problem

Inland open water capture fishing represents a major source of the overall production of fish within Bangladesh. A large portion of this fishing catch comes from the approximately 853,863 hectares of rivers and estuaries within the country. Despite several initiatives undertaken by the government and non-governmental organizations to ensure the conservation of open water fisheries stocks (such as restricting certain types of fishing nets, developing fish sanctuaries, and enforcing ban periods to develop the stock of indigenous fish, particularly Hilsha), overfishing continues to be a source of great consternation. Research suggests that open water fisheries management interventions undertaken by the Bangladeshi government, particularly with regard to Hilsha management have notably increased the income of smallholder fishers.1 However, this has done little to deter both the use of banned fishing nets and the penchant for overfishing among professional and life-long fishers, who cite poverty, lack of viable alternative income sources, and indebtedness as the main reasons behind this continued practice.2

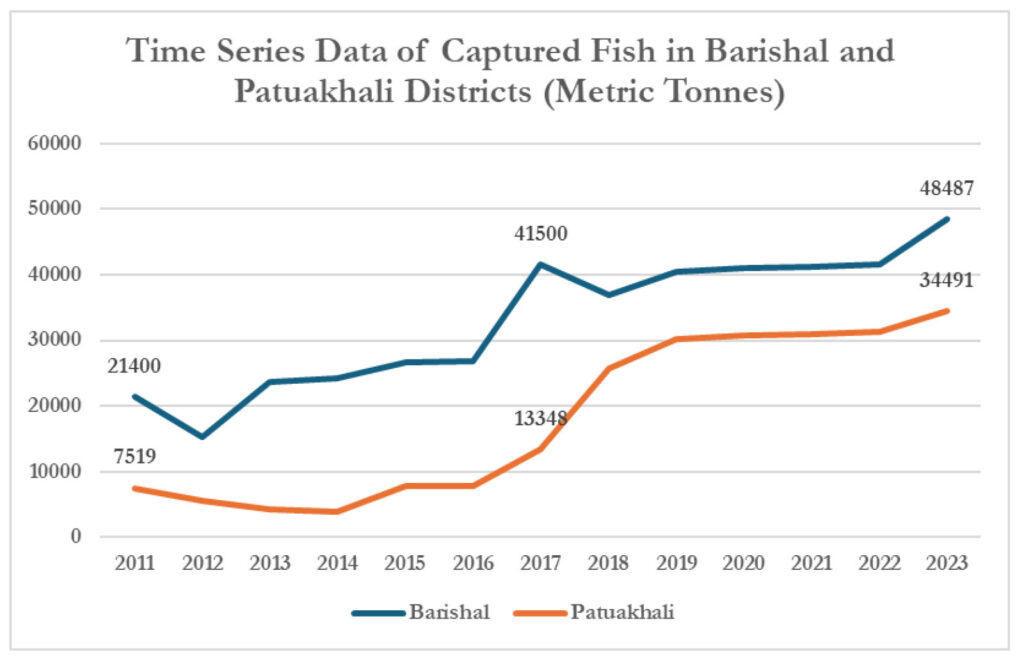

Overfishing represents a grave danger to a precarious riverine ecosystem that is already impacted by changing climactic conditions resulting in habitat loss, degradation of riverine ecosystems from river pollution and infrastructural development which changes the course of rivers and unsettles fishing stock. Data from the Department of Fisheries (DoF) yearly statistics suggests that there has been a continual upward trend in the amount of captured fish from rivers in Barishal and Patuakhali. The steady but continual rise highlights that fishing trends may have exceeded the rate at which fish are restocked naturally in rivers.

Figure 1. Time series data highlighting the annual amount of fish captured from rivers in Barishal and

Patuakhali between 2011 and 2023. Source: Department of Fisheries Yearly Statistics.

The DoF data suggests that the annual catch of fish from rivers in Barishal grew more than doubled, while in Patuakhali it increased more than four and a half times in the span of twelve years. This, by itself, even taking into consideration ongoing conservation practices signifies overfishing.

In the villages of Char Memania in Hizla, Barishal, and Char Dadhonia in Dasmina, Patuakhali, fishing represents one of the biggest sources of income. Due to their remote geography, and close access to rivers, a number of villages hold inhabitants who are entirely dedicated to fishing. Fishing households that are enrolled as participants in the B-PEMS AugroJatra Climate Change project reported having little to no educational qualifications among their household members and, reported having large amounts of ongoing debt from microcredit institutions which demanded substantial weekly repayments. In order to meet their debt servicing needs and to sustain their families, fishers entirely depended on the use of monofilament gill nets, colloquially known as current nets in local parlance. The characteristic of the gill net is its extremely small mesh network (25-50 mm) which is effective in catching even the smallest species of fish. The monofilament gill net has been identified by the Bangladeshi government as a major driver of overfishing and resource depletion given its ability to catch all species of fish. The government in 2002 banned the production, marketing, import, storage, transport and use of gill nets by amending the Protection and Conservation of Fish Act 1950. However, a lack of effective enforcement, awareness, and community buy-in has meant that its use has continued virtually unrestricted.

The Tragedy of the Commons?

Fishing households reported that the use of the gill net is a ‘necessary evil’ in that it allows them to catch fish to sustain their families and high debt burdens even during off-peak seasons. In comparison to other types of less intrusive nets, gill nets are cheaper and do not require extensive manpower or skills to maneuver. Additionally, all fishing households reported a growing scarcity of fish in the rivers. Each year’s catch is seemingly worse than that of the previous one.

‘Every year there is less and less fish and sometimes it depends entirely on fate. This year there is very little Hilsha in the river and we don’t have any other income options. We have to use the current net because it allows us to catch at least some fish when there is less fish in the rivers. However, we suffer losses when the police come and confiscate or destroy our nets. We then have to make another one.’ – Helal, Fisherman 3

The continued use of gill nets in the face of rapid depletion is akin to the allegory of sheepherders postulated by Garrett Harding in his famous essay the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’, where Harding hypothesizes that open access commons leads to a form of ruinous competition, where each individual is engaged in maximizing their own outcomes at the expense of everyone else, thereby leading eventually to a complete depletion of the resource itself.4 In this instance, the use of gill nets by each fisher in the same stretch of water leads to a situation where fish are caught at a faster rate than their stock can be replenished, leading to reduced income for all individuals in the long run and a reduced stock of fish.

Harding’s analysis, focusing on the misallocation of common resources, has largely been proven wrong by the work of noted economists Elinor and Vincent Olstrom, who, among others, have shown that access to common resources does not necessarily lead to ruinous competition. In particular, ensuring communication between all stakeholders as to their strategy, long-term community planning, and governance of common resources all directly impact the sustainability of common resources.5 In their summation of the conversation surrounding Harding’s conceptualization, Frishchmann et al. have pointed to the various interdisciplinary approaches that highlight how community-based forms of governance, which include buy-ins from local actors can be used to largely eradicate the pessimistic outcome of complete disintegration.6

An example of this kind of public resource management can be found in the Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) that the DoF has initiated, which allocates compensation in the form of rice to fishers as a means to respect periods of fishing bans. However, this ban enforcement has not been fully successful, primarily due to misallocation of the compensation whereby not all engaged in fishing or holding fisher identification cards (Jele Card) are recipients of the benefits. Some fishing households who are participants of the B-PEMS project also attested to receiving trainings from the DoF on fisheries management and the use of environmentally friendly nets. Why, then, does the use of monofilament gill nets continue unabated even as less and less fish are found every year? Why don’t the fishing households in remote areas of Barishal and Patuakhali adopt a cooperation-based strategy that could result in better long-term outcomes for everyone?

Role of Debt Bondage in Overfishing Scenarios

The reason why the scenarios in Barishal and Patuakhali resemble Harding’s doomsday scenario as opposed to the more optimistic outcomes proposed by Ostrom is due to the presence of an external constraint in the form of debt bondage. In reality, all fishing households in Barishal and Patuakhali reported being heavily indebted to both institutional lenders, mostly microfinance institutions, and informal lenders. The most curious among the types of debts currently held by fishers is the ‘advance’ or Daadon that they receive from fish wholesalers (Aarot-daars). Aarot-daars are essentially individuals who buy fish directly from the fishers at the jetty. All fishers reported that they had received a large amount of money in advance from Aarot-daars to catch fish in the rivers. The sum of this advance was reported between BDT 200,000 – BDT 500,000 for each individual fisher. They claim this money is used to finance the fishing trips, covering expenses such as boat repairs, net mending, and associated labor costs. Interestingly, this money is never ‘repaid’, in that the Aarot-daar never explicitly asks for this money back from the fishers. However, once the ‘advance’ is given, the fisher is essentially bound to the Aarot-daar and has to exclusively sell all their catch to only one person.

‘I received BDT 200,000 from the Aarot-daar to commit to selling my fish to him. This money helped to finance the fishing expeditions and paid for other household costs. He never asks for this money back. However, I have to sell all my products directly to him. If I sell it to someone else, then he will ask for this money back. In return, he sometimes pays me 5 to 10 taka less in commission per kilogram than I would have received in the open market.’

– Mamun, Fisherman7

While it may seem that the actions of the Aarot-daar are essentially securing suppliers of fish, the implications of the advance are far reaching. Not only does it mean that the fisher is to exclusively sell fish to the same individual (at a discounted rate), but it also means that the fisher must continue fishing to service this obligation. Due to their financial vulnerability, fishers are not able to directly buy themselves out of this obligation and must continue to fish to provide supplies to the Aarot-daar. If, for instance, a fisher decides to not engage in fishing, the Aarot-daar will immediately demand his money back.

‘We have to keep engaging in fishing throughout the year in order to sell fish to the wholesaler. If I decide to suddenly stop fishing, then not only I will lose out on my income, but also the Aarot-daar will ask for their money back. This amount of money can be bought out as well. If I wish to change agents, then the new agent has to pay the previous one in whole for the full amount that they paid me and then transfer this obligation to them.’

– Sadiq, Fisherman8

The Daadon, or advance, in practice is an example of debt-bondage, wherein fishers are linked to some form of fishing obligation for life. The only way to escape this service arrangement is to transfer it to another individual who may agree to buy them out. Smallholder fishers are thus trapped in a cycle that necessitates continuous fishing. As there is no repayment plan for this specific amount of money, it constitutes an unspoken promise to continue engaging in fishing and selling directly to the same individual. In the end, this debt is passed on to future generations of the fishing household. In all but two families that were interviewed, the male son of the household head was also directly involved in fishing.

Debt Bondage and Resource Depletion – A Novel Link

Overfishing and depletion of fisheries resources is therefore not a natural consequence of individual competition among smallholder fishers. It is a direct result of the kind of financing agreements under which the smallholder fishing industry is sustained in Bangladesh. Based on previous research conducted by the B-PEMS project, it is clear that the method of the Daadon is ubiquitous among fishing communities, and that each fisher is usually exclusively tied to a wholesaler who has fronted them a large amount of money. There is no expiration date to this debt and, over a period of someone’s life, it balloons to a very large amount of money which is impossible to repay. As a result of this constraint, fishers continue to engage in acts of self-interest that over time deplete collective resources, such as using current nets, which eventually leads to a poorer economic and environmental outcome for all those involved.

This type of lending, in return for buying out an individual’s services for an indeterminate amount of time, is illegal under Bangladeshi law. Despite there being no overt demand to return the money, the repayment is used as leverage to ensure the continued services of fishers who depend on catching fish for their livelihood. The Money Lenders Act, 1940 stipulates that any entity that engages in the lending of money must have a registered license. Similarly, the High Court in a judgment, in April 2022, directed the Central Bank to make a list of unauthorized money lenders and to take necessary legal actions against such practices. Debt bondage is also declared illegal under Section 9 of the Prevention and Suppression of Human Trafficking Act, 2012 (PSHTA). Despite these legal provisions in place, there is little to no enforcement of these provisions against the uniquely exploitative nature of the local fishing industry.

Approaches to community-based fisheries conservation and actions to improve the socioeconomic conditions of fishing households must, therefore, target this exploitative relationship at the heart of their practices, without which a sustainable solution to the problems is not possible.

Author – Ahmad Ibrahim (Program, Research, and Knowledge Management Advisor)

Facilitation – Ahmad Ibrahim, Zahirul Islam (Livelihoods and Skills Development Specialist), and Nasir Chowdhury (Project Director)

“This case study was funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.”