The keys to inclusive small business success in the South: Affordable finance and pro advice

For small business owners in the U.S. South like Tandra Jordan, Darius Walker and Jerrell Simpson, failure was never an option. But it was always looming.

Jordan is a single mom with two kids working full-time as a claims adjuster while trying to keep up with a fast-growing cleaning business in Little Rock, Ark. Walker is a globetrotting U.S. Army veteran who used G.I. Bill money to attend barber school; he now runs a busy barbershop and hair product business in Nashville, Tenn. Simpson is young and hungry to take his two-year-old personal fitness studio and protein powder line in Auburn, Ala., to the next level.

All three entrepreneurs are Black, relatively new to the fast-spinning world of small startups and have another thing in common: They tapped into a unique program offering access to affordable financing and business services to women- and BIPOC-owned entrepreneurs in selected Southern states.

SOAR is short for Southern Opportunity and Resilience Fund. It’s an affordable loan program to support underbanked, underserved entrepreneurs in 15 states across the South and Southeast.

Supported by a constellation of 11 Community Development Financial Institutions along with private impact investors and 45 community-based partners, since inception, the SOAR Fund has been a success. It has helped nearly 1,150 small businesses and nonprofits obtain almost $63 million in affordable loans, around 83% of which were distributed to women- or minority-led businesses. Yet entrepreneurs in some of the 15 states were more hesitant to take advantage of the unique financing opportunity, which made available loans that averaged nearly $55,000 at reasonable rates of 4%-6% interest.

With funding from Visa Foundation, Winrock launched SOAR Technical Assistance Program (TAP) in late 2021 to address the gap of SOAR applications in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia. TAP complements SOAR by helping minority-owned or led businesses and nonprofits surmount common barriers to obtaining financing such as issues with credit or collateral, organizing financials and projections, updating or assembling budgets and business plans, or tax considerations.

Pivotal moment.

As TAP rolled forward, Winrock and Visa Foundation staff began inquiring, communicating about and exploring what the targeted pool of entrepreneurs told them – and there were a few surprises.

“It was challenging at first to provide the kinds of technical assistance that would result in a SOAR loan application,” said Linsley Kinkade, Winrock’s senior director of U.S. Programs. “We listened to everyone, we listened to each other, we talked to Visa Foundation about it and we asked a lot of questions, including: ‘Should we continue to offer this assistance only to those interested in SOAR?’” Or was there another, larger opportunity to provide more nuanced support to women- and minority-owned businesses in those states?

“Clients were telling us they needed help but not necessarily tied to one loan product,” said Tonitrice Wicks, a Winrock senior program officer based in Jackson, Miss. “They might need help putting together comps to figure out pricing. Setting up a business account, tracking financials, figuring out taxes. Any and all of those things.”

Winrock pitched the idea of adapting the approach to Chukwudi Onike, program officer at Visa Foundation. Onike understood that the financing landscape for small entrepreneurs, even in underbanked rural areas, was rapidly evolving as COVID unfolded. “The technical assistance and investment readiness training was still going to be an important gap to fill irrespective of whether clients went to the SOAR Fund or to other sources of capital,” Onike said. “So we broadened the aperture and were able to reach more entrepreneurs and more small businesses as a result of opening up and casting a wider net.”

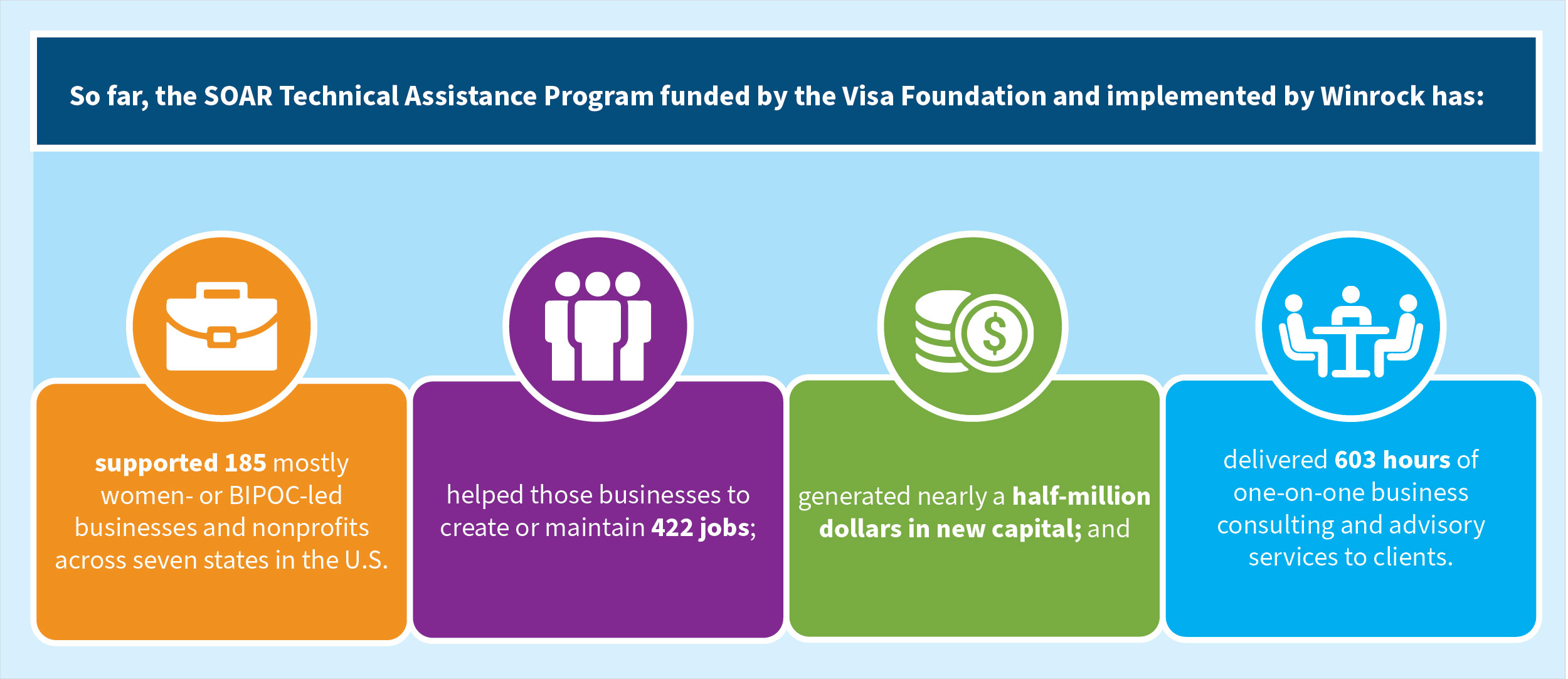

So far, TAP has assisted 185 businesses across all seven states, helped those businesses to create or maintain 422 jobs and generated nearly a half-million dollars in new capital, while delivering 603 hours of one-on-one business consulting and advisory services to clients. Part of that success results from the close collaboration between Winrock and Visa Foundation, combined with the skill and commitment of experienced business consultants available to TAP participants, whether they opted to apply for a SOAR loan in the end, or not. As Onike, says, calibrating the approach was “really about focusing on our ‘North Star’ – and that’s unlocking more capital for entrepreneurs and driving more economic activity.”

The veteran barber of Brentwood.

Darius Walker, the Army-vet barber in Nashville, is happy the program has continued. Though he never applied for a SOAR loan, he says he’s deeply appreciative of the advice, encouragement, expertise and connections facilitated by his TAP business advisor and mentor, John Riggins, an experienced enterprise coach and former business school teacher from Arkansas. Walker’s Cali Barber shop, located in Nashville’s upscale Brentwood area, has begun thriving since the pandemic lockdowns and related economic slump crimped his business.

Originally from Oakland, Calif., Walker served with the U.S. Army in Afghanistan, Korea, Iraq, Israel, Czech Republic, Albania, Germany, Hungary, Texas and finally Fort Campbell, near Nashville, before he retired. He opened in 2017 and now has more customers than he can handle. But he’d really like to do fewer cuts, beards and brow work, and more specialty oil production and sales.

“So we’re talking about, ‘How do you do that?’” said Riggins, Walker’s TAP advisor. “Darius is in this interesting transition period because his beard oil is starting to take off. One of the challenges is he’s too small for the big bottlers and manufacturers, so he’s got to figure out how to make it until he can get to critical mass when bigger players might get involved.”

Like other TAP advisors, Riggins has spent time getting to know Walker, building trust, understanding his market, and helping him think through his approach.

“If you’re selling through Amazon, how do you ramp up?” Riggins said. “Hopefully you begin selling through your own website so you’re not spending 15-30% of revenues on fulfillment. So we’re talking about that – and branding. We’re thinking about trying to find someone who is an influencer to help him reach his target markets.”

Walker says of Riggins: “He’s like a conduit … He just really wants to see me win. It feels good to talk to someone who isn’t just checking boxes, who really wants to help.”

The support adds up to more than weathering COVID, inflation and remaining afloat. Walker wants to build the kind of business that enables him to invest in his community and serve as a role model for other entrepreneurs. He’s already doing that, sponsoring a popular annual back-to-school backpack giveaway.

On the impact of TAP and programming that aims to reach underbanked entrepreneurs, Walker says: “Keep it going. There’s not a lot of opportunities to do well here in the South if you’re a minority. You really have to work a whole lot harder because the financing doesn’t come to you. You have to have money, and you have to spend money to get your project going.”

The unusual case of Ms. Tan’s OCD Cleaning Service.

Tandra Jordan agrees with that assessment. A single mom with a full-time day job, Jordan started her own cleaning business in Little Rock as a side hustle at the start of the pandemic with one employee: herself. But business picked up as contagion-generated interest in cleaner homes and offices spread, and Jordan’s tiny enterprise, Ms. Tan’s OCD Cleaning Service, was suddenly in demand. When Amazon surprised her with an inquiry about a contract to clean a local warehouse, Jordan needed to staff up and gear up with more equipment and supplies – immediately.

She applied for and received a small SOAR loan to bridge the gap between signing her first commercial contracts and receiving payments for early invoices. Jordan also had an exchange with David Moody, a TAP business advisor and former U.S. Small Business Administration official who was excited to see Jordan’s business taking off. Jordan was looking for larger commercial jobs and had already registered to do some government contracting, Moody said.

“She was talking about marketing, needing to do some advertising and find funding, getting a forecast model ready so she would know what to expect, along with an internal budget – all things that would help her when she was trying to acquire capital.”

Where would she be if she hadn’t been able to get the loan?

“If I couldn’t pay them (new employees) back then when I got those contracts, they weren’t going to work,” Jordan said. “So if I can’t even fulfill the small contracts, how am I going to get the bigger ones?” She adds: “In the South it’s harder because there’s not a lot of minority business owners in that high-income bracket who are in the position to help their own communities,” which makes it harder for some inexperienced entrepreneurs to start up, expand and succeed.

Business fit in Alabama.

Like Jordan, Jerrell Simpson, a young personal fitness instructor in Auburn, a college town in eastern Alabama that swells with new residents each August, also took a chance on a startup enterprise during the COVID era. He opened his workout studio on University Drive in 2021 despite the lurking uncertainties of the still-rampant pandemic.

During a recent phone interview, when another phone at the gym rang, he took it: “This might be money!” Back on the line, he explains how he got involved with SOAR, his work with TAP and what’s ahead for J. Simpson Fitness.

“I’m single with no kids, and my gym is my baby,” he says. “I knew with this venture I was going to have to double-down on learning things from the business side. If I was going to close, it wouldn’t be because I was a bad trainer, it’d be because of the ins and outs of the financing. It’s harder getting loans from traditional bank lenders even though I have good credit.”

He connected with TAP’s John Riggins, and successfully obtained a loan through a SOAR-related CDFI. He used the money to beef up his marketing, including an attractive website, an app for a soon-to-launch online fitness program, and labeling for his protein powder line. The capital also helped him get through an unexpectedly difficult period: As COVID subsided, inflation set in, and some customers began dialing back on discretionary costs and fees for things like the gym.

The work with Riggins and TAP helped Simpson with what he calls his back-of-the-house affairs: “Applying for loans, cash flow statements, all those little details that can make or break a business.” Riggins sends him forms, offers advice and helps him stay on top of the numbers. “All that stuff that matters so much when you are applying for financing.”

“We’re all in this together.”

What’s next? Both TAP business advisors and the entrepreneurs they support use similar terms to describe what’s needed now and what they hope to leave behind. Each seeks to support or establish the kind of financial stability that feeds business growth and further investment in their communities. The TAP entrepreneurs also see themselves as potential role models for those to come, and a common phrase comes up when they talk about what they want to build: “Generational wealth.”

Simpson extends the thought, saying it’s partly “generational knowledge” of financial literacy that’s been missing in some places. But that’s beginning to change through a combination of smart approaches, the bespoke and flexible consulting services offered by TAP, ingenuity and plain old work.

“There are a lot of hardworking intelligent people that love what they do, and there are a lot of women and minorities that could use the help,” Simpson says. “You know, we’re all in this together.”

Related Projects