Faces of the Value Chain

How a groundbreaking USAID program is bolstering both Nepal’s agricultural ecosystem and those who depend on it

When Kumar Thapa was a young boy growing up in the green, rolling hills of midwestern Nepal, he knew exactly how he wanted to occupy his days. “I wanted to study,” says Thapa, now 24, as he sits amidst rows of ripening tomato and chili plants that cover the hillside plot of land where he spent his childhood.

Tall and lean with a thatch of jet black hair, Thapa speaks quietly, almost in a whisper, as he recounts how circumstances ultimately kept him out of the classroom. Though Thapa relates his tale without emotion, the story itself and the setting in which he relates it are full of drama. As he talks, the horizon fills with sprawling charcoal gray clouds, which will soon dump summertime monsoon rains on the pocket of the Surkhet District of Nepal where Thapa lives.

Like so many of the 80 percent of Nepalese who rely on agriculture for their livelihoods, Thapa’s parents were subsistence farmers who grew just enough wheat and corn to keep the family fed throughout the year. Because money was tight and Thapa’s parents needed him around to help on the farm, school just wasn’t an option. When he got older and started his own family, Thapa followed a path familiar to legions of young men living in rural Nepal who want to build a better future. “I went to Qatar as an electrician, but I did not earn enough money,” he says. “I could not get a good job, so I came back.”

When he returned to the same plot of land and the same dim economic prospects, Thapa knew he had to try something new. He had some experience growing vegetables in what he calls a “kitchen garden,” so Thapa experimented with cultivating a few tomato plants. It was a smart move: tomatoes, cucumbers, cauliflower and a range of other vegetables can flourish in Surkhet’s relatively cool hills in the late summer and fall. By contrast, the flat and more densely populated Terai region nearby is too hot and wet for farmers to grow vegetables until wintertime. The result: Thapa had an opportunity to become a commercial vegetable farmer with a large, eager market willing to pay good prices for his vegetables a short distance away.

From that first plot of tomato plants, Thapa has both expanded the variety and amount of vegetables he grows and dramatically improved his farming skills. Thanks to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded Knowledge-based Integrated Sustainable Agriculture and Nutrition (or KISAN, which means farmer in Nepali) project, Thapa has received training about the best technologies and techniques to use to maximize the amount of tomatoes, chilis, cucumbers and other vegetables he grows. This has allowed Thapa to make the transition from subsistence cereal farming to commercial vegetable production.

The results for Thapa, his wife, Kamala, and their two young children are transformative. Moving from subsistence to commercial vegetable farming has doubled Thapa’s income, allowing him to purchase more land to cultivate and to invest in better seeds, fertilizer and equipment – including a plastic house for growing tomatoes – that allows him to bolster the quantity and quality of his crops.

Perhaps most satisfying, Thapa’s children will never share his unfulfilled dream of an education. “I have been investing my income from vegetables into the study of my children,” Thapa says. “I have two brothers. I have invested some of my money into their study also.”

Fostering virtuous connections

Thapa’s story is becoming more common in Nepal, thanks in large part to the success of the KISAN project. Launched in 2013 as part of USAID’s Feed the Future Initiative, KISAN aims to reduce poverty and hunger in Nepal by raising the incomes of smallholder farmers like Thapa. Nepal is a poor nation whose already tenuous food security has been challenged by domestic conflict, a devastating 2015 earthquake and the slow creep of climate change. Over the course of the four-and-a-half-year project, KISAN has worked to help 100,000 households in 20 districts around Nepal. These households were selected because they had the lowest per capita income, the least access to nutritious food and, not coincidentally, the greatest prevalence of health problems related to malnutrition.

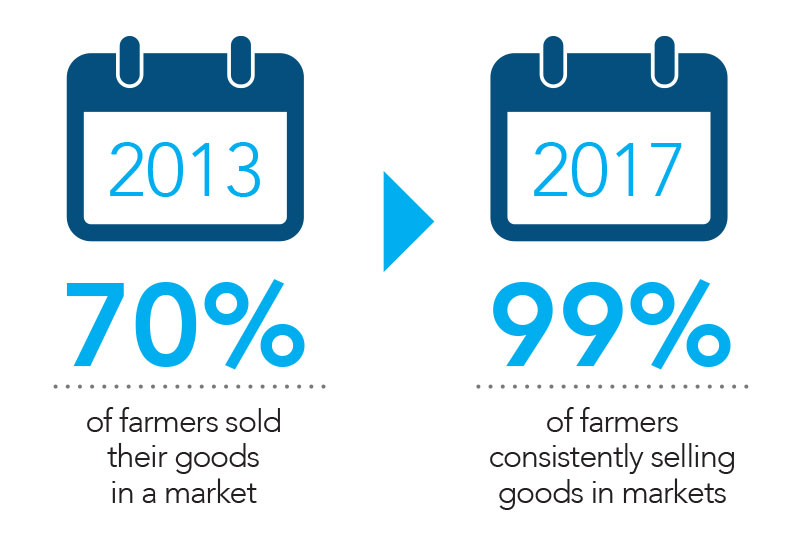

Helping thousands of smallholders make the transition from subsistence to commercial farming has produced genuine results. Two statistics stand out. When KISAN began, only about 70 percent of the selected farming households sold any of their goods in a market, and many who did so only sold small quantities on a sporadic basis. Today, 99 percent of the farming households are consistently selling what they grow in markets. That near universal embrace of commercial farming has substantially elevated incomes for KISAN participants.

“Average annual household sales of agriculture products increased more than 300 percent in FY 2015 over the baseline period, growing from $250 to $1,113, an increase of $863 per household.” says Phil Broughton, chief of party for the KISAN project. In a country where the per capita income is around $2,400, that’s a significant increase.

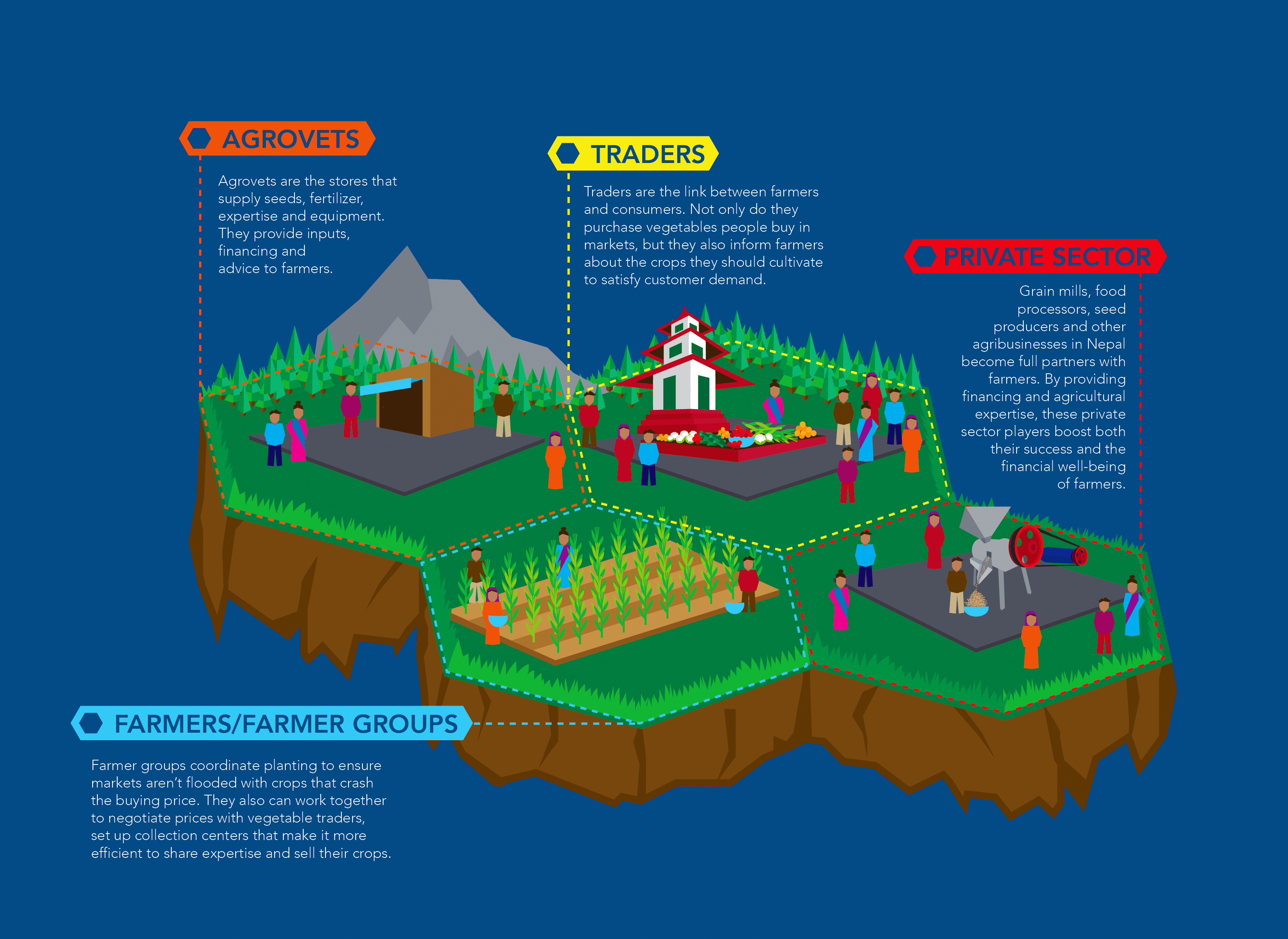

But while KISAN focuses on farmers, it’s unique in recognizing that farmers cannot succeed in a vacuum. True, it provides training to farmers about the wisdom of planting crops in rows, incorporating elevated beds and managing pests, and has been doing so since its inception. But it also forges longlasting, mutually beneficial relationships among the wide universe of players in Nepal’s agriculture sector.

To do this, KISAN takes what’s known as a “value chain” approach to forge those necessary connections. For instance, farmers need to collaborate closely with Nepal’s many agrovets: stores that supply seeds, fertilizer, expertise and sometimes financing in order to maximize the quality and quantity of what farmers grow. At the same time, farmers must have close working relationships with the traders and wholesalers who buy their crops and get them to consumers. There are also bridges to be built among farmers themselves, who can then collectively strengthen their bargaining position with traders and coordinate what to grow each season. This collaboration keeps the markets from being inundated with so much tomato or cauliflower that the price collapses.

Of course, this web of connections has another name: a market. KISAN — in a significant departure from many development projects — is designed to tap the power of free markets. It does this for two reasons: because profit is a powerful motivator and because the goal is to make the project obsolete. “Unlike a lot of agriculture programs, which depend on subsidies, KISAN is working on really changing the market system,” says Jeff Apigian, a program officer at Winrock International, who has helped spearhead the KISAN project.

It’s one thing to understand how a value chain works on a hypothetical level. Grasping why it works in practice, though, requires acknowledging human nature, specifically self-interest. Indeed, a value chain works when increasing the income of a farmer like Kumar Thapa is in the financial self-interest of everybody else in the chain.

For instance, an agrovet owner like Bhim Prasad Poudel needs to recognize that helping farmers is the best way to help himself and his family. Though they’re longstanding pillars of Nepal’s agricultural scene, agrovets like Poudel have traditionally been content to remain in their shops and wait for farmers to make a purchase. Actively acquiring new customers and servicing existing ones has rarely been a top priority.

For Poudel, that changed after he received training from KISAN. Today, the kind-faced Poudel is more than willing to step away from the tidy shelves of his Bishal Agrovet Center in Surkhet. When local farmers tell him a crop isn’t growing as they’d hoped or insects are ravaging their plants, Poudel will visit their fields to diagnose the problem and suggest a solution. Sometimes, he’ll invite farmers to inspect, and hopefully copy, how he grows rice, wheat and vegetables at his garden at home. Recently, Poudel has even been offering loans to cash-strapped customers who need to purchase seeds or other inputs at planting time. It’s money that gets paid back when his customers harvest their crops — and presumably will cement their loyalty to his business.

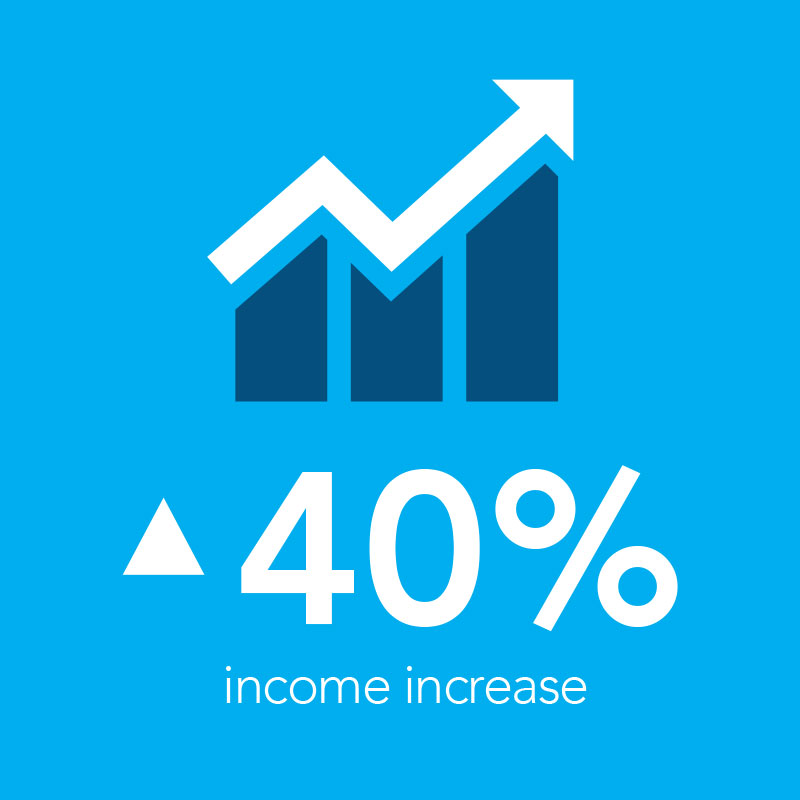

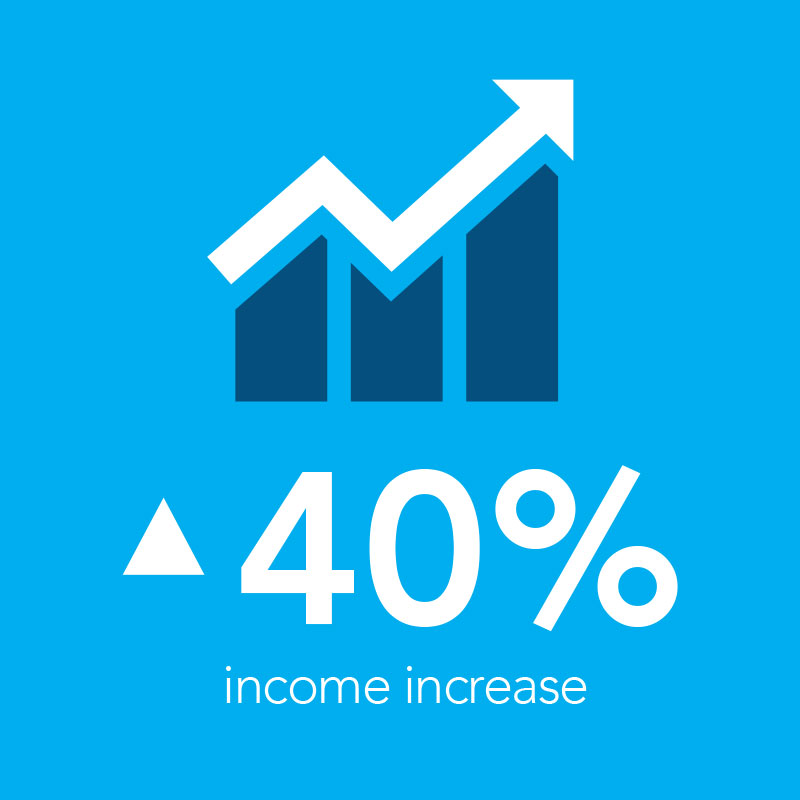

This customer-focused approach has helped Poudel expand his business by 40 percent, increasing his income enough to help send his grandkids to school and make improvements to his home. “I have renovated my house with cement and bricks,” he says. “Before, it was covered by wood.”

This customer-focused approach has helped Poudel expand his business by 40 percent, increasing his income enough to help send his grandkids to school and make improvements to his home. “I have renovated my house with cement and bricks,” he says. “Before, it was covered by wood.”

Agrovet owners like Poudel who provide financing and training will be increasingly important as KISAN winds its activities down in 2017 — particularly because the network of government agriculture extension workers able to provide farmer education and training is not sufficient to meet the demand. If Poudel’s plans for the future are any indication, the local farmers he serves should be in good shape. “I’m planning to increase my customer number by adding more innovative technology so they are attracted to my agrovet,” he says. “My business will grow and my income will increase.”

Trading up

And so it goes along each step on the value chain — disparate individual self-interests, once they’re connected, lift the economic opportunity and prospects of a multitude of people. In fact, Poudel’s daughter-in-law, a vegetable trader named Rama Poudel, operates the storefront next door. Though location and family ties connect the businesses, their storefronts look starkly different; the agrovet’s shop is neat and orderly, while Rama Poudel’s store is, by necessity, cluttered with the ever-changing selection of vegetables she has for sale. On this summer day, there are bags bursting with cucumbers and piles of beans and chilis arrayed in front of Poudel, along with a scale she uses to weigh and price the vegetables she sells. As she makes sales, Poudel keeps one eye on her toddler son as he repeatedly tries to tumble out onto the busy street.

Though the appearance of the two shops offers a sharp contrast, their similarities are more consequential. Like her father-in-law, Poudel also received training from KISAN about how to run a better business. “Before the KISAN project, I didn’t know how to keep the records of profit or loss,” she says. “But now I am keeping the record of profit or loss and I know I have good profit.” She also benefits from the credit her agrovet father-in-law provides to farmers, which gets deducted when they deliver vegetables to her store.

Poudel also understands that her business has benefited from KISAN’s successful efforts to connect her with local farmers. In the past, Poudel imported about 80 percent of the vegetables she sold to customers from farmers in India — a lost opportunity for the local economy. Today, 80 percent of the vegetables she sells come from local producers.

“Now, due to the KISAN project, they have taught most of the farmers regarding commercial vegetable farming,” she says. “Therefore we have lots of production nearby.”

Even better, Poudel has developed close relationships with her local suppliers, particularly the area’s many women farmers. “As a female, I think I have gained the trust from the female farmers,” she says. Now she’s able to tell them what kinds of vegetables are most in demand, knowledge that helps her sell more to the customers and buy more from the farmers. It’s the kind of dynamic that should be self-perpetuating once the KISAN project ends next year.

Indeed, Poudel neatly summarizes the future goal for everyone along the value chain. “I want to make bigger sales,” she says, “and to sell lots of vegetables to lots of customers.”

Related Projects