Acacia tortilis: Fodder Tree for Desert Sands

NFTA 91-01, April 1991

A quick guide to useful nitrogen fixing trees from around the world

Acacia tortilis, often called the “umbrella thorn’ for its distinctive spreading crown, is one of the most widespread trees in seasonally dry areas of Africa and the Middle East. The umbrella thorn is the dominant tree in many savanna communities and provides an important source of browse for both wild and domesticated animals.

Botany

Acacia tortilis (Forsk.) Hayne (subfamily Mimosoideae, family Leguminosae) is one of about 135 African acacia species. Unlike the Australian acacias, African acacias are armed with thorns and produce highly palatable pods. A. tortilis is a variable species, with six intraspecific taxa including four recognized subspecies: tortilis, spirocarpa, heteracantha, and raddiana (Brenan 1983). Although some French and Israeli authors consider ssp. raddiana separate species (A. raddiana), recent revisions treat it as a subspecies (Brenan 1983, Ross 1979). As with other African acacias,, A.tortilis is a polyploid complex most are tetraploids (2n=4x=52); ssp. raddiana is an octoploid (2n = 8x = 104).

Acacia tortilis varies from multi-stemmed shrubs (ssp. tortilis), to trees up to 20 m tall with rounded (ssp. raddiana) or flat-topped (ssp. heteracantha and spirocarpa) crowns. The presence of very long thorns and two thorn types, long-straight and shorter-hooked distinguish Acacia tortilis from other acacia species in Africa. The alternate leaflets (usually < 1 mm wide) are smaller than those of most bipinnate acacias. White or pale-yellow fragrant flowers cluster in 1 cm diameter round heads. Flowering is prolific with up to 400 flowers/meter twig. Flowers later develop into bunches of spirally twisted, indehiscent pods. Straight pods also occur, though rarely (Somalia and Kenya). Pods vary considerably in size depending on provenance but range from 8 to 12 cm long. Ecology

Acacia tortilis occurs throughout dry Africa, ranging from Senegal to Somalia and down into South Africa. In Asia, trees occur in Israel southern Arabia, and Iran. A. tortilis is found in all countries fringing the Sahara and is often the tree that extends furthest into the desert. Young A. tortilis forms natural thickets in heavily over-grazed savanna in southern Africa. The tree was introduced from Israel in 1958 into the district of Rajasthan, India, where it showed the greatest promise of 277 tested species. It is now widely planted in Rajasthan and has also been planted in Pakistan and on the Cape Verde Islands.

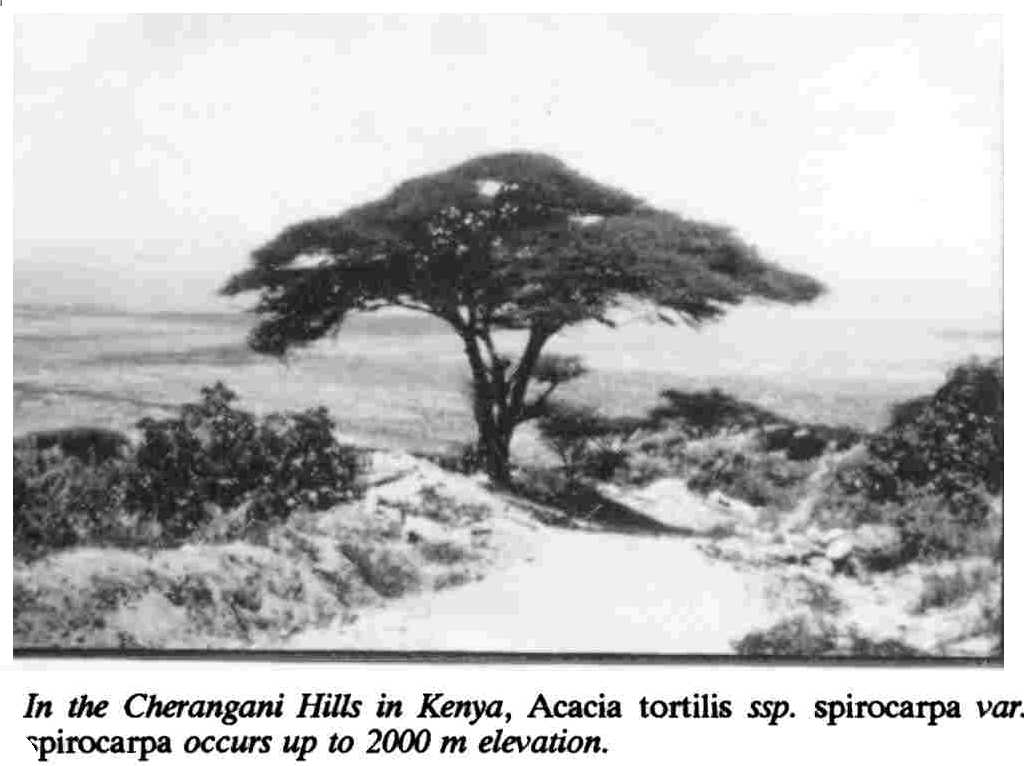

Acacia tortilis occurs from sand dunes and rocky scarps to alluvial valley bottoms, avoiding seasonally waterlogged sites. A very drought resistant species, the umbrella thorn grows in areas with annual rainfall as low as 40 mm and as much as 1200 mm, with dry seasons of 1-12 months. The tree favors alkaline soils but will colonize saline and gypseous soils. A. tortilis forms a deep tap root in sandy soils; the solitary landmark Tenere tree in the southern Sahara had roots reaching 35 m deep. On shallower soils and in and sites, it can develop hose-pipe subsurface roots extending over twice the width of the crown. The umbrella thorn ranges from 390->2000 m elevation. It survives sites where temperatures regularly reach 500C at mid-day and fall to near freezing at night. Older trees (>3 m tall) ran withstand frosts and light grass fires.

NODULATION. A. tortilis nodulates frequently over its natural range. Considerable variation in modulation levels has been found under controlled environmental conditions. Fast-growing Rhizobium strains have been isolated at Dundee University.

USES. Forage: In semi-arid areas, Acacia tortilis provides a staple browse especially for camels and goats. Forage is available throughout most of the dry season when other sources are scarce. In the Turkana region of Kenya, large riverine trees (called ekwar) are individually owned. Pods are collected for sale in markets, such as in Lodwar (Turkana) and Msinga (South Africa), both as animal and human food. Pods are also fed to lactating animals to increase milk yields. Pods and leaves have a good level of digestible protein (mean = 12%) and energy 6.1 MJ/kg DM (Le Houerou 1980), as well as being rich in minerals. Seeds are high in crude protein (38%) and phosphorus, an element usually scarce in grasslands. The pods require milling to increase digestion in cattle. Over 90% of the tree’s flowers abort and drop from the trees, providing an additional important forage (Kayongo Male and Field 1983).

Few studies have quantified A. tortilis fodder production, but an estimated 1 dry ton/ha/yr shoot and leaf growth was available in semi-deciduous bushland in the Tugela Dry Valley, South Africa (Milton 1983). Yields from young plantations in India indicate similar productivity- 2.5 kg/tree/yr (at 400 trees/ha), discounting pod (1 kg/tree/yr by age 7) and fuelwood production (Gupta and Mohan 1982).

Silvipasture: A. tortilis provides shade for animals. Some of the most palatable grass species grow beneath its canopy (Walker 1979). In Turkana, Kenya, soil nutrients and herbaceous plant productivity and diversity were significantly greater under than away from the tree canopy (Weltzin and Coughenour 1990).

Sand dune stabilization and sheiterbelts: A. tortilis has been used with some success to stabilize, sand dunes in Somalia, United Arab Emirates, and Rajasthan, India. In India it has been grown successfully in sheiterbelts with Azadirachta indica.

Wood: The dense, red wood of A. tortilis makes very good charcoal and fuelwood (4360 Cal/kg) (BOSTID). It burns slowly and produces little smoke when dry. Poles are commonly used in hut construction and for tools. The wood of

ssp. heteracantha is durable if water-seasoned. The tree resprouts vigorously when coppiced and is managed for fuelwood in natural woodlands in Sudan. In plantations in India, trees are planted at 3 x 3 m spacing and coppiced for fuelwood. After 10-12 years over 50 tons/ha wood can be harvested. In other areas the trees are not cut, to avoid reducing pod yields.

Other uses: In traditional pastoral societies every part of Acacia tortilis is used. The high value held by local people for the tree is reflected in the detailed nomenclature given to its cycles of development. In Oman, for example, local people call A. tortilis by more than a dozen different names in Dhofari arabic.

Flowers provide a major source of good quality honey in some regions. Fruits are eaten in Kenya, the Turkana make porridge from pods after extracting the seed, and the Masai eat the immature seeds. The bark yields tannin and the inner bark cordage. Thorny branches are used for enclosures and livestock pens; roots are used for construction of nomad huts (Somali and Fulani). Leaves, bark, seeds, and a red gum are used in many local medicines. Two pharmacologically active compounds for treating asthma have been isolated from the bark (Hagos et al. 1987).

PROPAGATION. A. tortilis is a pioneer species easily regenerated from seed. Pods are best collected by shaking them from the canopy. In East Africa, a mature tree can produce over 6000 pods in a good year, each with 8-16 seeds (10,000 – 50,000/kg depending on the subspecies).

Seeds are often extracted by pounding pods in a mortar followed by winnowing and cleaning. The hard-coated seeds remain viable for several years under cool, dry conditions. They require pretreatment for good germination. Mechanical scarification works best for small seed lots. Soaking seeds either in sulfuric acid for 20-30 minutes, or in poured, boiled water allowed to cool, are both effective treatments (Fagg and Greaves 1990).

Seed are planted in the ground in 1 cm deep holes or in the nursery in 30 cm long tubes. Rapid tap root growth requires frequent root pruning. Seedlings are ready to be planted out after 3-8 months. On marginal sites, initial seedling growth is often slow but quickens once roots have reached a water source. For best growth, plants should be weeded and protected from browsing animals for the first three years. At Jodhpur, India (320 mm annual rainfall) average height of 20 selected 2.5-yr-old plants was 3.8 m.

Limited seed supplies are available from natural populations in a number of countries, primarily in Sahelian Africa, and from landraces in India. A broader range of germplasm is available From the Oxford Forestry Institute (South Parks Road, Oxford OXI 3RB, LTK) for establishment of field trials. Small quantities of seed from Kenyan provenances are also available from NFTA.

PESTS AND LIMITATIONS. A large number of insects have been recorded to attack living trees, but only bruchid beetles are of economic importance. They can destroy over 90% of seeds produced in any year. The buprestid beetle (Julodisy sp.) defoliated over 50% of a plantation in Rajasthan. Acacia tortilis is also susceptible to nematodes, mistletoes (Loranthaceae), and galls. Large numbers of insects and mammals feed on the flowers. In India, powder post beetles (Sinoxylon spp.) can reduce the wood of felled timber to dust over a period of weeks. A further consideration is in humid to subhumid areas where A. tortilis can become weedy if it is not being used (BOSTID 1979).

PRINCIPAL RFFERENCES:

BOSTID. 1979. Tropical legumes: Resources for the Future. National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C.

Brenan, J.P.M. 1983. Manual on taxonomy of Acacia species: Present taxonomy of four species of Acacia (A. albida, A. senegal, A. nilotica, A. tortilis). FAO, Rome, Italy. 47 p.

Fagg, C.W. and A. Greaves. 1990.,4cacia torwis 1922-1988. CABI/OFT annotated bibliography. No. F41. CAB International Wallingford, Oxon, UK.

Gupta, T. and D. Mohan. 1982. Economics of trees versus annual crops on marginal lands. Centre for Management in Agriculture (CMA), Monogr. No. 81. 139 p.

Hagos, M., G. Samucisson, L. Kenne and B.M. Modawi. 1987. Isolation of smooth muscle relaxing 1,3-diaryl-propan-2-ol derivatives from Acacia tortilis. Planta Médica 53(l):27-31.

Kayongo Male, H. and C.R. Field. 1983. Feed quality and utilization by cattle grazing natural pasture in the range areas of northern Kenya. In W. Lusingi (ed), IPAL Report A5. p. 230-245.

Le Houerou, H.N. 1980. Chemical composition and nutritional value of browse in tropical West Africa. In H.N. Le Houerou (ed), Browse in Africa, the Current State of Knowledge. ILCA, Ethiopia. p. 261-289.

Milton, SJ. 1983. Acacia tortilis ssp. heteracantha productivity in the Tugela dry valley bushveld: Preliminary results. Bothalia 14(3-4):767-772.

Ross, J.H. 1979. A conspectus of the African Acacia species. Memoirs of the Botanical Survey of S. Africa No. 44. 155 p.

Walker, B.H. 1979. Game ranching in Africa. In B.H. Walker (ed), Management of Semi-Arid Ecosystems. Elsevier, Amsterdam. p. 55-81.

Weltzin, J.F. and M.B. Coughenour. 1990. Savanna tree influence on understory vegetation and soil nutrients in northwestern Kenya. J. Veg. Sci. 1:325-334.

Written by Christopher Fagg, Department of Plant Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3RB.