In Cities, Water Security is a WASH Issue

As John Feighery of mWater explains, water security is not just a rural concern.

Over a long weekend in September, Dar es Salaam suffered a water shortage, causing residents to store water in tanks or buy more expensive bottled water for drinking and cooking. When the water came back on, people living close to the water main used up all the available pressure to refill their tanks, leaving those in the outlying areas to wait for days until the water reached them again. Everyone needed to boil their water because when the pressure was gone, dirt or raw sewage from leaking septic tanks may have seeped into the pipes through cracks or loose connections.

This home copes with intermittent water supply by combining an underground and an overhead tank. The underground tank has a float valve to ensure that as soon as there is any water pressure at all, the tank will start filling. When the water is off they pump water up to the overhead tank, which supplies the house.

Anyone who has lived in a developing megacity would recognize this situation as routine. What set this apart was that it was a not a routine shortage, but a rare scheduled outage necessary to carry out planned maintenance on a valve. Anyone who has not been to Dar es Salaam in a while, a city formerly known for water insecurity, will be especially surprised to hear that this is now a rare event. Thanks to recent major supply investments made by the Government of Tanzania in partnership with the Millennium Challenge Corporation and Exim Bank of India, the Dar es Salaam Water and Sewerage Corporation (DAWASCO) is now able to supply 24-hour water throughout much of their service area.

Why is water security a WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) issue? Consider the Sustainable Development Goal Target 6.1 for drinking water: to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all. There are obvious benefits to having enough water available for all uses in the home, including cooking, washing, bathing, and gardening. But the on/off cycle of intermittent or rationed water supply also impacts water quality, affordability, and equitable access.

Emerging research confirms that an intermittent water supply is incapable of ensuring safe water to the end user. This is why water secure cities issue boil water advisories on the rare occasion that a water main loses pressure. When the pressure is cut off, all the households downhill use up every last drop. This actually creates suction in parts of the pipe, and contaminated water from the subsurface will rush in through every crack or loose fitting. Considering the prevalence of on-site sanitation throughout developing country cities, there is always a ready source of untreated sewage released into the subsurface ready to enter a leaking pipe.

Poor households lack the resiliency to store or purchase supplemental water, making equitable access unachievable without water security. Those who can afford it resort to filling enormous tanks with water from trucks, which can easily cost 10 times as much and offers no guarantee of safety, given the shady practices of many private water suppliers. Others purchase bottled water for drinking and make due with water from salty and contaminated shallow wells to wash dishes and hands, which can easily lead to illness from food contamination or inadequate household hygiene. The extreme poor can’t afford bottled water so they drink from whatever shallow sources are available, and are faced with the difficult decision of whether to use precious fuel for boiling water or for cooking.

Dar es Salaam is rapidly transforming into a water secure city — in every DAWASCO office I visited, there were lines of people waiting to request new connections. When a utility is able to provide a reliable supply of water every day to most people, customers — including the poor — are more willing to pay for piped water over the other alternatives, creating a virtuous cycle of increasing revenues to support operations and maintenance. This also means the utility will have a lower risk profile to potential investors, resulting in greater access to finance to support new capital investments needed to supply their rapidly expanding customer base. As utilities expand their coverage — pipe by pipe — the risk of waterborne disease and the economic burden of not having enough water is reduced.

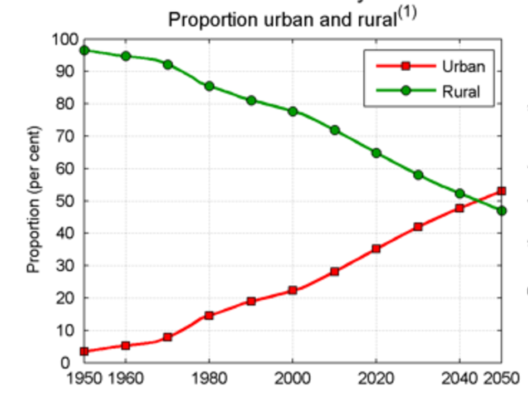

Predicted urban versus rural population in Tanzania through the year 2050, when it is expected to become a predominantly urban country. (Source: UN DESA, Population Division (2014): World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision)

By 2050, more people will live in cities in Tanzania than in rural areas, yet strategies within the WASH sector are still focused heavily on rural self supply. Cities are politically and socially complex, but donors such as MCC have shown that improvements to water security can produce cross-cutting benefits, not just in WASH but also in health, economic security, and equitable access to basic services. Repairing and supporting existing utilities is the low-hanging fruit of SDG6, ensuring the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all through a water secure future.

This post originally appeared on mWater’s Medium page. For more information about mWater, visit their website here.

Related Projects