In Mali, Girls Thrive Despite the Challenges

Innovative program continues to educate youth amid the pandemic and political instability

Growing up in rural Mali, Sali Kassogue had never been to school. That all changed in 2018 when then 11-year-old Sali started attending an accelerated schooling center (ASC) through the USAID-funded Mali Girls Leadership and Empowerment Through Education (GLEE) program.

Implemented by Winrock International, Mali GLEE operates more than 300 ASCs that provide a specialized, accelerated nine-month curriculum to Malian children – mostly girls – with little or no previous education. The goal of the accelerated learning program is to support girls’ transition to Mali’s government schools.

After nine months in which she became the top student in her class, Sali became one of those students. Sali now attends a government school. “Sali is better than many students that were already in school here,” her teacher, Sekou Traore, says. “She is among the best in reading, grammar and writing.”

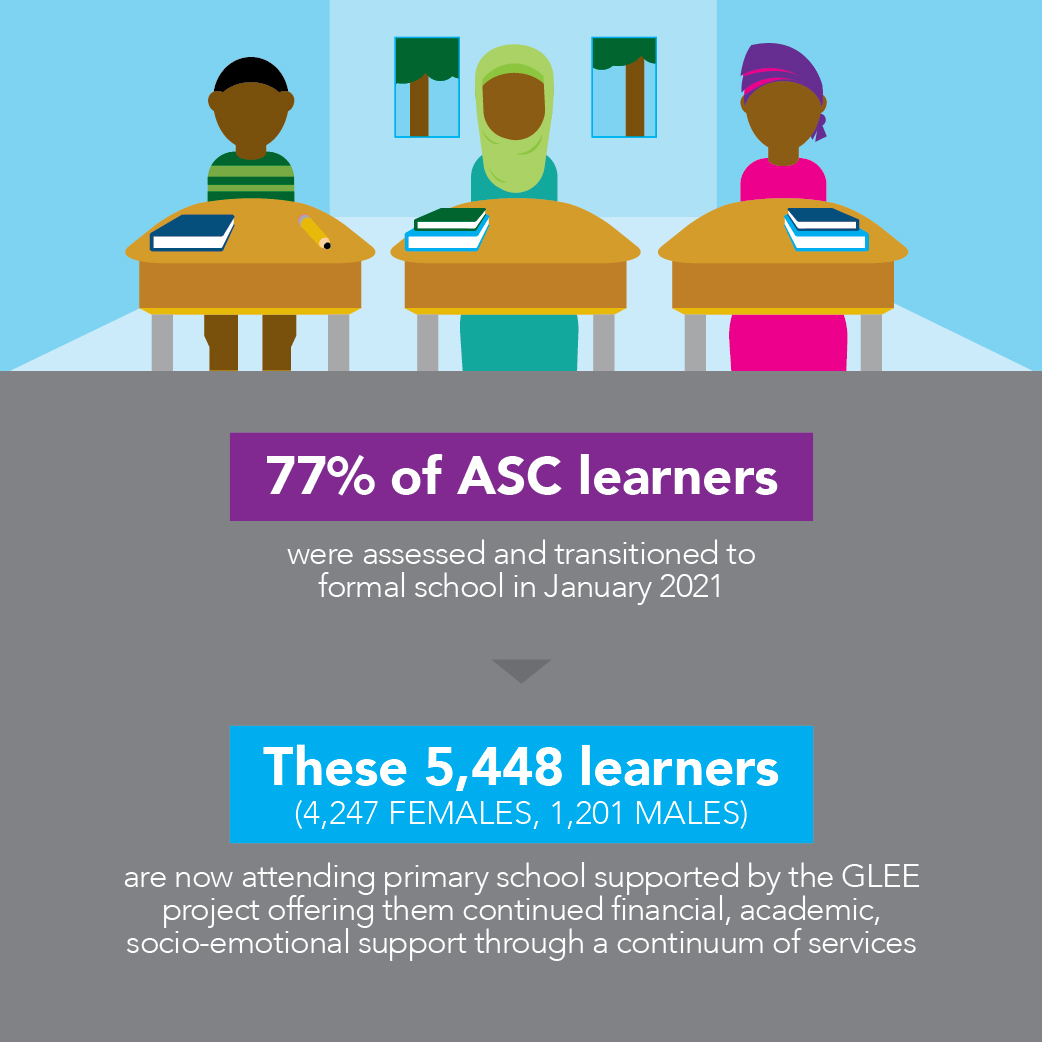

Sali’s story is emblematic of Mali GLEE’s efforts to improve the quality of life for Mali’s girls through education, even in the face of instability and challenging conditions. Of the students who attended GLEE schools in 2019-2020, 5,448, or 77 percent, will attend government-run primary schools supported by the GLEE project, which will provide continued financial, academic and socio-emotional support through a continuum of services. A total of 12,807 students were supported with scholarships in the form of support to school management committees to implement key activities in their school action plans, which address barriers to girls’ enrollment and retention in school.

These numbers come despite a host of challenges that made education a daunting task for Mali in 2020. The period was marked by teachers’ strikes between January and June, and the closure of schools in March caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to these challenges, GLEE pivoted to working remotely through its established network of local leaders, mentors, youth ambassadors and peer educators, effectively adapting its approach to small group work during the three-month period of school closures. Continued engagement with these community stakeholders enabled GLEE to re-open its ASCs in June with the majority of learners attending.

Mali also experienced a coup d’etat in August, its second in eight years. The country has recently been plagued by terrorist violence that sometimes targets schools, and ethnic conflicts between farmers and herders have also led to violence. GLEE has found success in overcoming these hurdles through strategies that empower people at the local level.

In Sangafara, a village in the western Malian province of Kayes that is surrounded by gold mines, consistent school enrollment and attendance has been a problem for years. GLEE implemented a school in the village in 2019, registering 43 girls, nine of whom had never attended school, as well as two boys. A month into the program, enrollment dropped to 23 as the pupils began to leave to assist their mothers with gold mining. In response, GLEE brought village elders and local mothers together, which resulted in a community-led monitoring committee. Committee members went door-to-door in the village focusing on mothers of children rather than the students directly. Within two weeks of forming the committee, the school not only welcomed back all the girls who had dropped out, but enrolled new girls. The committee continued to monitor attendance daily, and enrollment remained full through the 2019-2020 school year.

Another important priority for the GLEE program is to nurture and empower female leadership. One example is GLEE’s youth ambassadors and peer educators’ program, which trains and prepares selected youth in project communities to raise awareness among their peers on themes relevant to healthy growth and development. These youth communicate with their peers about sensitive issues so they can successfully cope with fear, stress and the embarrassment of discussing difficult topics with their parents.

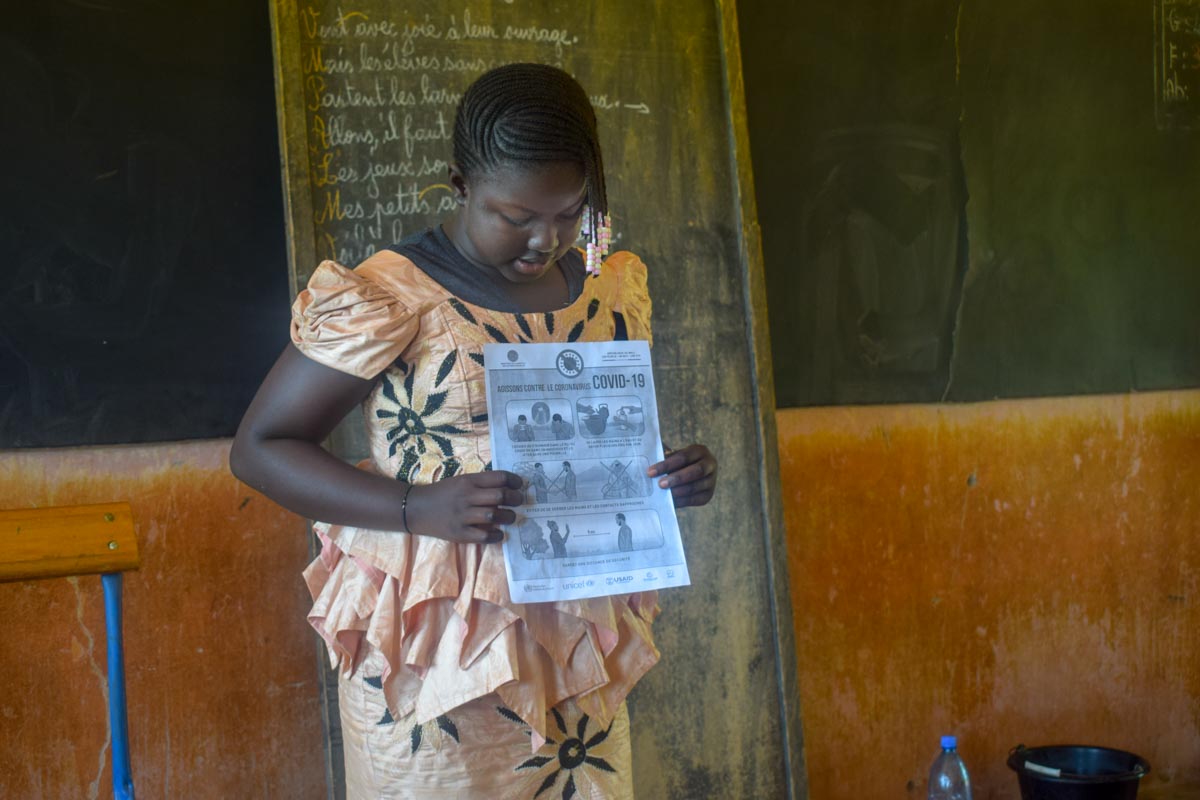

Lala Dianka, 12, is one of 336 peer educators trained by GLEE in Kayes Province. Through the training, Lala learned how to speak to her peers about sensitive topics such as menstrual hygiene management, prevention of early pregnancy, types of contraception and infectious disease prevention, as well as the value of education and the risks associated with gold mining. Polite, supportive and an exemplary student, Lala brought together over 20 children (both girls and boys) each week to discuss youth education and the protection of girls. Her work was highlighted during the 2020 Youth Ambassadors Forum and the International Family Planning Day organized by GLEE in Kayes, when Lala gave a 30-minute presentation on contraception, family planning, and COVID-19 prevention measures at Sadiola school in front of more than 100 people of all ages.

“I’m no longer afraid to speak in front of a large audience, let alone my comrades,” Lala says. “Thanks to GLEE, I am a peer educator, a leader in my village!”

Another bright young leader from the GLEE program is 18-year-old Hawa Tapily. Hawa was married at 15 and gave birth to a baby boy, but she wanted to continue her studies. Supported and encouraged by her GLEE mentor, Hawa convinced her mother-in-law to support her studies by speaking about the benefit of educating girls in their community, pointing to the example of another local girl who had completed her studies despite being married. Together the two women then addressed the topic with Hawa’s husband and convinced him to let her continue her studies.

Once back in school, Hawa began gathering with other students to discuss taboo practices such as family planning and the consequences of early marriage and early pregnancy, which often hinder the development of young girls in her community. “I started chatting with other girls because I don’t want them to go through the same thing as me,” Hawa says. “I also know that on my own, I could not succeed in breaking the silence on certain customary practices that are harmful to the development and well-being of the girls in the community. But if many are informed, awareness will become easy.”

Next school year, Hawa plans to attend high school and continue her education. “Education will allow me to take good care of my family, my children and maybe support my husband economically one day if I do well,” she says.

Related Projects