Local Heroes

Trafficked men become best friends and entrepreneurs — sharing their story to save others.

Saiful and his friend Kalam* are as close as brothers. They work together in an easy rhythm, laughing and talking as they sort the day’s harvest of shiny green brinjals (eggplants). Looking at the men now it’s hard to imagine what they endured — and survived. “I thought I was trapped forever,” Saiful says. “I thought I would always be a slave.”

In late 2014, a man named Jahid told Saiful and Kalam about a work opportunity in Malaysia. They would need passports, Jahid said, but he could arrange those if they paid him $1,200. The men were excited. They were eking out a living as day laborers, and this was a way out. But Jahid soon asked them for more money — first for visas, then for medical exams and tickets. Saiful and Kalam didn’t have this kind of money, so they turned to their families, who sold a cow and some land to come up with the cash.

Soon the men were taken by bus from their home in southwest Bangladesh to the capital city of Dhaka, where they boarded a flight to their new life. But when they reached Malaysia, Saiful and Kalam were locked in a room for seven days, their papers confiscated, then driven to a palm field to work. After a month of hard labor Saiful demanded the salary he was promised. “But the farm owner said, ‘You were sold to me — you must work here for a year,’” Saiful recalls. Jahid had taken their fees and their salary, and they were left with nothing. They had become two of the more 1,531,300 Bangladeshis — that’s almost one percent of the nation’s population — estimated to be living in modern-day slavery.

Saiful and Kalam are fighters, though, so they made a run for freedom. But they had traveled only a few kilometers before the Malaysian police picked them up and jailed them for being in the country illegally. It was another low point — but also the beginning of their return home. After three months and more money (once again scraped up by their families) Saiful and Kalam were released from jail and returned to Bangladesh in late 2015.

Saiful and Kalam are fighters, though, so they made a run for freedom. But they had traveled only a few kilometers before the Malaysian police picked them up and jailed them for being in the country illegally. It was another low point — but also the beginning of their return home. After three months and more money (once again scraped up by their families) Saiful and Kalam were released from jail and returned to Bangladesh in late 2015.

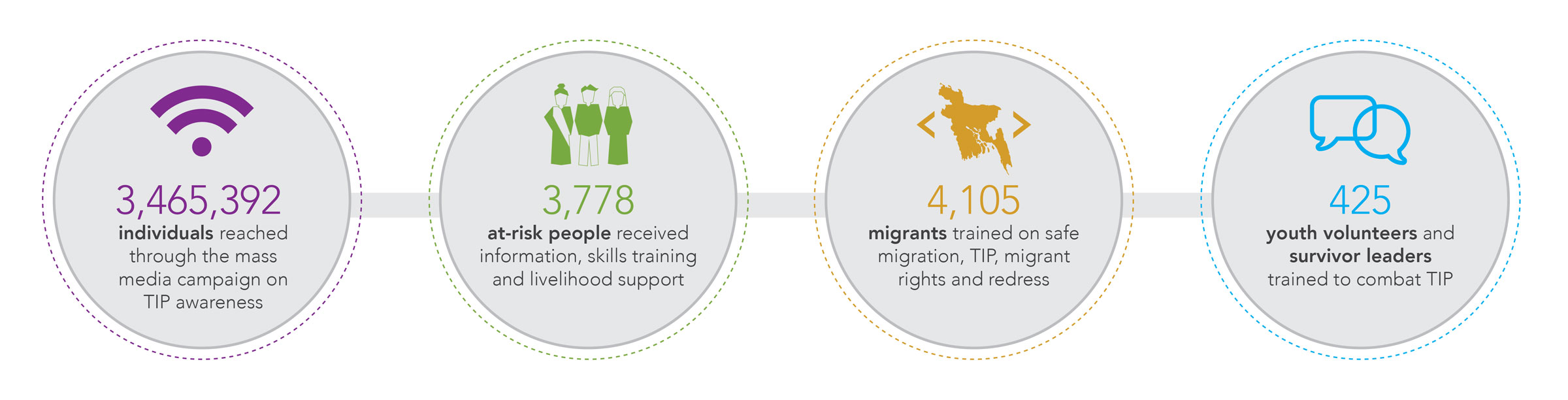

When they arrived in their home district, Jessore, a local official told Saiful and Kalam about Winrock’s Bangladesh Counter Trafficking in Persons (BC/TIP) project, funded by USAID, which has provided 3,778 trafficking survivors with comprehensive assistance — including trauma counseling and life skills training — since it began in 2014. Through BCTIP and one of its 11 local partners, the Dhaka Ahsania Mission, Saiful and Kalam took a livelihood skills class and an entrepreneurship training program. Through the classes they became close with Mahmud, who had also been in forced labor and jailed in Malaysia. The men bonded over their shared experiences, and the entrepreneurship class gave them an idea. They no longer had land to work — it was sold to pay the trafficker’s fees — but they were young and strong. This time they would hatch a real escape plan — one that relied not on leaving but on staying. They would start a farming enterprise together.

That was a year ago. Now the three men lease four fields together. One brims with beans, which in mid-August are abloom with delicate lavender flowers. The others are planted with brinjals, which the men show to visitors as they load the vegetables into baskets bound for market. It’s not the best yield they’ve had — heavy monsoon rains have damaged the crop — but they receive almost $20 for today’s haul, more than they thought they’d get. After paying rent and other expenses they’re clearing about $400 a month — more than they’d make working abroad.

That was a year ago. Now the three men lease four fields together. One brims with beans, which in mid-August are abloom with delicate lavender flowers. The others are planted with brinjals, which the men show to visitors as they load the vegetables into baskets bound for market. It’s not the best yield they’ve had — heavy monsoon rains have damaged the crop — but they receive almost $20 for today’s haul, more than they thought they’d get. After paying rent and other expenses they’re clearing about $400 a month — more than they’d make working abroad.

Believe it or not, “many trafficked individuals want to go back because they make so little here,” says James Baidaya, a project officer with BC/TIP. “But these three are working together and skipping the middleman, so all the profits belong to them.” The men plan to continue farming together. They have become local heroes, Baidaya says, and have plans for the future. “I would like to have a cattle-fattening farm,” Kalam says. But not alone, he adds. Whatever he does, he wants to do it with Saiful and Mahmud.

“Earning money again is OK, but getting my family back was the best,” Saiful says, explaining that at first his parents blamed him for making a bad decision. But Saiful’s mother, Nilima, seems to have forgotten about that now. “When Saiful returned I was crying. I was very happy to have my son back,” she says.

Kalam’s wife, Ranya, says, “I thought my husband would never come back.” As she talks, Kalam holds the couple’s baby son, Rakib, born after the ordeal. Ranya and the couple’s 13-year-old daughter, Farhana, had to shift for themselves during the long months when Kalam was away. “We had no income for that year,” Ranya says. “We had to borrow from relatives.”

The monetary debts are being repaid now, thanks to the vegetable sales, and the men are paying it forward another way, too. Through BCTIP, Saiful, Kalam and Mahmud learned of ANIRBAN (which means “the flame that never dies”), an organization that provides information and support to trafficking survivors. As ANIRBAN members, the men speak to groups of villagers and students, warning them of the ruses traffickers will assume, sharing the basics of safe migration — and telling their own stories. “There are 16- to 17-year-olds who try to pass themselves off as 18 to get a passport,” Mahmud says. “They are ripe for trafficking.”

Saiful, Kalam and Mahmud are grateful for the second chance they’ve been given. But they want to help others make the most of their first chances and avoid the mistakes they made. “It is our pleasure to inform others about safe migration,” Mahmud says. “We suffered a lot. We don’t want others to suffer, too.”

*All names in this story have been changed.

Related Projects