Resource

Endless Cycles of Debt-Bondage – A Case Study of Fishers in the Sundarbans

The findings of this case study are based on focus group discussions carried out by the Bangladesh Program to End Modern Slavery (B-PEMS) AugroJatra team with fishers and women of Sutighata village, in Koyra upazila in Khulna, bordering the Sundarbans. All names used in this case study have been changed to protect anonymity.

Fishing in the Sundarbans: A Costly Affair

The fishing communities living near the Sundarbans, a mangrove forest on the border of India and Bangladesh, depend primarily on the fish they catch from within the forest. The Sundarbans is located at the confluence of three rivers, and the Arpangashia river carries a multitude of fish, shrimp, and crab species, making it a lucrative spot for small fishers to earn their keep.[i] Both men and women engage in fishing, with men mostly making long trips deep into the forest and women working near the shores with nets. However, fishing near the Sundarbans is a cost-intensive endeavor. The entire area is watchfully regulated by the Forest Department, from whom the fishers need to obtain a pass every time they venture into the forest for fishing. Local communities have alleged that Forest Department officials often demand payments, or a share of fish caught in return for providing the passes.[ii] Overhead costs are also substantial, with each week-long fishing trip costing upwards of Bangladeshi taka (BDT) 10,000 ($92), which includes fuel, food, an extra worker on the boat, and fishing equipment. In recent years, the window for such trips has become narrower, with the Forest Department implementing bans during the breeding seasons to ensure the availability of fish.[iii] Currently, there are two separate annual moratoria on fishing –June through August for all kinds of fishing and January and February for crab fishing. The bans mean that fishing communities have an average of seven months during which they can go on fishing trips, leaving them with no steady income from the forest during the remaining months.

How it is Financed

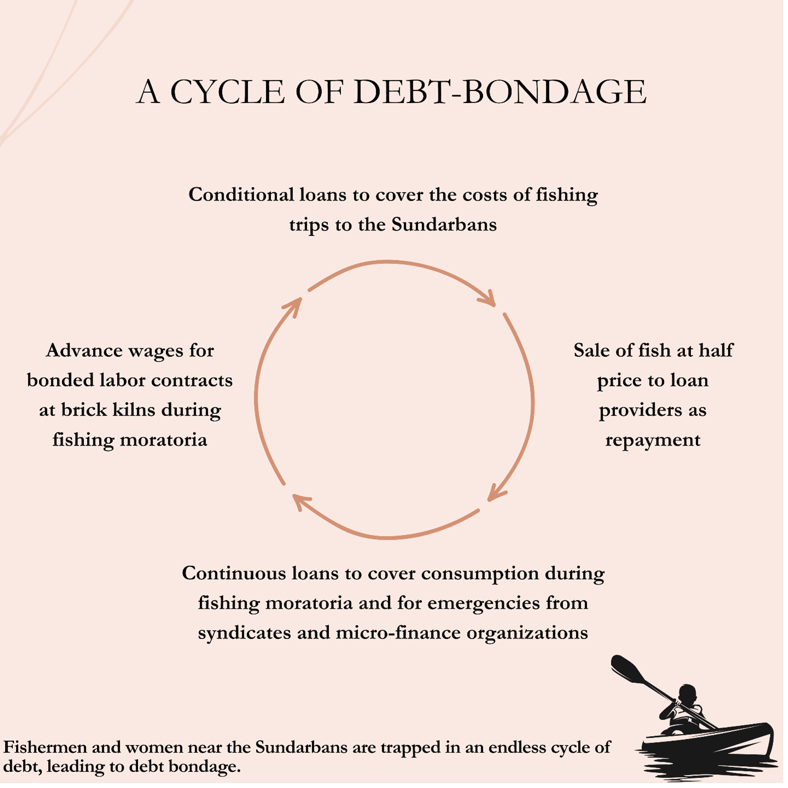

Almost the entirety of a fishing expedition is financed through informal debt. The fishers depend completely on the Aarot-daar[iv] to provide them with an advance loan through which they can fund their weeklong fishing trips.[v] These loans are provided with a special clause – that the fishers can only sell their catch to the Aarot-daar who lent them the money. Because of this, fishers are forced to accept a reduced price per kilogram of fish (in some cases, almost half of what they would receive in the open market). However, because they are unable to come up with the regular injections of up-front capital required to finance these expeditions, the fishers become dependent upon the Aarot-daars. If a fisher wishes to utilize the full length of time during which fishing is permitted in the Sundarbans, they require between BDT 70,000 – 80,000 ($640 – $732) of capital every year. The unpredictable nature of fishing makes the fishers deeply dependent upon the Aarot-daars for the money (some fishing trips may yield less than the costs, while some may yield more). This effectively traps the fisher into a cycle of debt which they are unable to extricate themselves from.

Mountains of Debt

The debt burden on the fishers does not only come from the Aarot-daar. Formal and informal loans are ubiquitous in the communities, and all of the individuals the team spoke to were in the process of paying back multiple loans. These loans are usually a mix of informal ones from Aarot-daars, micro-credit loans from NGOs, and other informal sources such as extended family. None of the fishers had access to formal credit from banks, and the interest rates on all their loans were very high.[vi] Banks were particularly inaccessible due to their distance from the communities, the documentation requirements, and their requirement for a mortgage.

“Sometimes there is no choice. If I have a medical emergency in the family, who will i go to, in order to get the money? No organization will lend to me. That’s when I have no choice but to fall at the feet of the company and ask them for more money.”

– Sohag, Fisherman

Beyond the capital costs involved in fishing, a large amount of the money borrowed is spent on consumption. Fishers must borrow continuously in order to meet the daily needs of their families. In some cases, individuals reported taking out micro-credit loans to pay back other loans, effectively increasing their debt burden in the long-term. In such circumstances, the fishers become increasingly dependent on the Aarot-daar for other forms of loans as well – ranging from consumption to medicalemergencies to marriage. As one individual put it, “Sometimes there is no choice. If I have a medical emergency in the family, who will I go to, in order to get the money? No organization will lend to me. That’s when I have no choice but to fall at the feet of the company[vii] and ask them for more money.”

With each loan taken on, the debt burden keeps on rising, until it reaches unmanageable proportions. However, there is no pay-back period for these loans – these are for life. As long as the fishers and their family live in the community, they must continue to fish and sell their produce to the lender. The Aarot-daar maintains the entire history of borrowing of the fisher within his books.

“Everything is written in that book. Nothing escapes their notice. If I borrow a handful of rice from him, He will not it down. I sometimes think my entire fate is written in that book!”

– Anwar, Fisherman

Lean Periods – Opening the Door to Modern Slavery

Fishing communities now must contend with five months without any kind of fishing activities, and consequently, income. The bans have been put in place as a response to overfishing and the reported impacts of climate change, which has reduced the fish population in the rivers of Sundarbans.[viii] While the government has instituted a program to give identification cards to fishers and provide them with food rations during the ban periods, those who have received the support reported that it was insignificant. [ix] To combat the lack of income during these periods, more and more men from the fishing communities choose to migrate for seasonal jobs, most commonly in brick kilns, located across Khulna and Gopalganj in Bangladesh and West Bengal in India. Brick kilns have long been associated with some of the worst forms of labor, including bonded labor and debt-bondage.[x] In the specific case of the fishing communities in Koyra, Khulna, the appeal of brick kilns comes from the practice of advance payment (Daadon). Each laborer is provided with the wages for his work in advance, with amounts ranging between BDT 20,000 to BDT 50,000 ($183 – $275) depending on the duration of their contracts. This advance amount greatly supports the fishers to pay back the accrued interests on their loans and to ensure the survival of their families during the periods fishing remains banned. Once they have received the advance, the individual essentially becomes bonded laborer, forced to carry out work and stay at the brick kilns.

Financial insecurity puts a strain on families’ resources, leading to instances of child marriage.[xi] The porous Bangladesh-India border at the Satkhira-West Bengal frontier of Bhomra further facilitates cross-border migration and trafficking into brick kilns. One female fisher, who had crossed the border remarked on the ease with which the crossing takes place, “How easy is it? You can go to Badamtola (local bazaar) right now and you will find a long line of people ready to take you across the border. The price per head is high, and is higher than it has ever been, but it is still relatively straight forward. You have to cross a river and then a forest and keep running. It helps if you have someone waiting on the other side.”

Link to Climate Change and Associated Vulnerabilities

It is not evident from their responses what the impacts of climate change have been on the fishing community’s livelihoods. However, the highly salinized soil has meant that drinking water can no longer be naturally obtained. Residents of the village now must purchase and transport drinking water from another location, often at great physical and financial cost.[xii] This added strain on resources exacerbates the already vulnerable position that fishers find themselves in. Fishers have also reported having to spend a longer time out in the forest with each passing year to catch a desirable amount of fish. This may be linked to the depletion of the fish population already documented. However, what is clear is that more and more fishers are turning to working in brick kilns due to the prospect of receiving advance wages. Some fishers have noted that the fishing calendar sometimes clashed with the season for brick kiln work (usually during the winters) and due to the low yield and associated costs, many individuals had chosen to go work in the brick kilns instead of fishing.

“How easy is it? You can go to Badamtola (local bazaar) right now and you will find a long line of people ready to take you across the border. The price per head is high, and is higher than it has ever been, but it is still relatively straight forward. You have to cross a river and then a forest and keep running. It helps if you have someone waiting on the other side.”

– Sulekha, Fisherman

[i] Habib, Kazi; Neogi, Amit; Oh, Jina; Nahar, Najmun; Kim, Choong-Gon; Lee, Youn-Ho, ‘An overview of fishes of the Sundarbans, Bangladesh and their present conservation status’, Journal of Threatened Taxa, (12), 15154-15172, 2020. DOI : 10.11609/jott.4893.12.1.15154-15172

[ii]Findings from the focus group discussion conducted by the Winrock B-PEMS team with fishing communities in Koyra. Dated – 7 August 2023.

[iii] UNB, ‘Tourism, fishing banned in Sundarbans for 3 months,’ Dhaka Tribune, Last modified – 31 May 2022. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/289089/tourism-fishing-banned-in-sundarbans-for-3-months

[iv] Fishing trips are primarily week-long and coincide with phases of the lunar cycle. Within each lunar cycle of 30 days, fishers can carry out a maximum of two expeditions (once during Shuklopokkho, the period between the new moon and the full moon, and once during Krishnopokkho, the period between the full moon and the new moon). Fish are usually found most between the 6th and 13th of these two 15-day periods, which are called Goans.

[v] In local parlance, an Aarot refers to a large store or warehouse of any kind of goods. Usually, aarots are the term used to denote warehouses or stores of goods from which buyers can purchase at wholesale rates. An Aarot-daar is the individual in charge of the aarot. Here it refers to the wholesaler of fish, who directly purchases from fishers to then sell to retail markets across the country.

[vi] Micro-credit interest rates have been capped by the Micro-credit Regulatory Authority (MRA) of Bangladesh at 24 percent. No such cap exists for informal personal loans, which, according to the FGD participants, did not have a fixed percentage but rather a compoundable amount on every thousand taka of cash (or goods) borrowed, to be paid back within a stipulated timeframe. Usually, this would be between BDT 90 – 130 per thousand taka for a fixed number of months. Failure to pay back within the given time would see the amount double with each passing period.

[vii] Fishers colloquially called the Aarot-daar a company, highlighting the structured nature of the lending and buy-back system. All of the fishers in the community are linked to these fish purchasing syndicates that provide them with credit.

[viii] Dasgupta, Dhruba, ‘Fish population declining in the Sundarbans’, The Third Pole, Last Modified – 17 December, 2018, https://www.thethirdpole.net/en/climate/fish-population-declining-in-the-sundarbans/

[ix] The government scheme to provide compensatory food rations to fishers is run by the Department of Fisheries in collaboration with the Ministry of Social Welfare. The scheme has so far managed to bring 2 million fishing households into its purview, with a large number still left out. Under the scheme, those with identification documents provided by the Department of Fisheries are entitled to 45kg of rice for a 60-day ban period and 30kg of rice for 30 day ban periods.

[x] Gunnupuri, Aarthi, ‘The horror of modern-day slavery in India’s brick kilns’, Equal Times, Last Modified – 10 March 2017, https://www.equaltimes.org/the-horror-of-modern-day-slavery?lang=en

[xi] The team interviewed one such individual, who was married at the age of 13, who was subsequently trafficked to India to work in a brick kiln to pay off the debts taken on by her husband’s family.

[xii] Women reported having to travel long distances by rickshaw vans and fill their pitchers with water and come back. In some cases, fresh water is also supplied by dealers to the homes of the community members.