Resource

From Crisis to Exploitation – A Case Study of Displaced Returnee Migrants in Satkhira

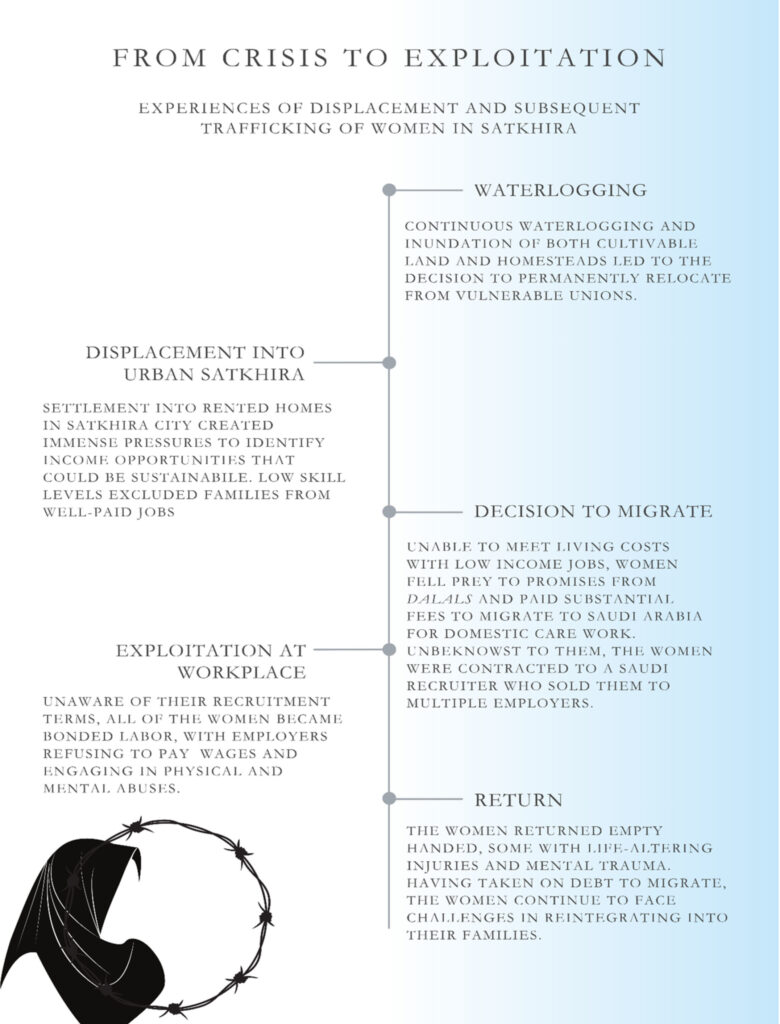

The findings of this case study are based on focus group discussions carried out by the Bangladesh Program to End Modern Slavery (B-PEMS) AugroJatra team with returnee women migrants in Satkhira city, displaced from their homes in Shyamnogor and Assasuni upazilas due to waterlogging. All names used in this case study have been changed to protect anonymity.

Initial Displacement Due to Waterlogging

Residents of low-lying areas within Assasuni and Shyamnagar upazilas in Satkhira, in southwestern Bangladesh, must continually contend with the problem of waterlogging.[i] These areas remain at risk of flooding and subsequent waterlogging when rivers swell due to heavy rainfall or storm surges during cyclones. In both instances, residents face regular breakdowns of dams or, in the case of storm surges, water overflowing the dams. In the absence of proper drainage, entire villages remain waterlogged for months on end. The phenomenon dates back to the construction of polders in the 1960s to stop the inundation of low-lying floodplains by the then East Pakistani government. Although the locals received a momentary reprieve from flooding, the polders slowed down the flow of water in the rivers, building up sediment and effectively raising the level of the land around the embankments. The result has been a lack of natural drainage of water following storm surges or heavy rainfall, eventually leading to a state of semi-permanent waterlogging.[ii] According to the residents, since the turn of the century, instances of waterlogging have increased in frequency. This has, over time, meant that communities dependent on agriculture were no longer able to engage in farming activities. Some have made the switch to aquaculture, particularly shrimp farming given the high salinity in the water, but for those whose homes remain submerged year-round due to waterlogging, there is little choice but to leave everything behind. During this period, members of these households began to engage in seasonal migration to urban centers to find work. Many took up jobs in brick kilns and construction industries to supplement the limited income they could generate in their village. These patterns of seasonal migration slowly became more frequent, until families decided to relocate completely to urban areas. Between 2010 – 2015, a number of families decided to make this move and resettle in Satkhira city, in the hopes of finding better livelihood options.

“When there would be cyclones or storms, the water would come in and usually take a few months to recede. But over the years, the water level just did not recede. And when it did, the land was so highly saline, there was no way to grow anything. At one point, when our houses also started getting inundated regularly, we decided to move to the city. We had exhausted all options for earning a living in the village.”

– Shopna, returnee migrant

However, the families did not fare much better in the city. Having primarily come from agricultural backgrounds, they lacked the qualifications required for employment in semi-skilled industries. As a result, most had to look for daily-wage labor jobs in construction, domestic care work, and other positions requiring manual labor. The financial pressures of living in rented housing and having to purchase all kinds of food inputs meant that very quickly the families became indebted to both formal and informal lenders.[iii]

Risky Migration and Experiences of Abuse

One common factor for all the women who made the decision to migrate to Saudi Arabia was the financial insecurity under which the decisions were made. In every case, the woman was given examples of other women in their localities who had migrated abroad and were now earning handsome sums of money. The dalals[iv] were often individuals that the women or their family members knew and trusted. Many women were promised wages as high as BDT 60,000 ($545) per month working as domestic workers.

It is pertinent to note that under the Musaned program, female workers migrating to Saudi Arabia can enjoy zero-cost migration, where the entire process of recruitment is paid for by the recruiting agencies at the destination and employers. However, abuses of the Musaned system are well-documented and woman migrant workers have reported paying hefty fees to facilitate the migration process regardless.[v] The surplus payment is absorbed by dalals and recruiting agencies in Bangladesh.

Prior to their departure, the women were not aware of the type of contract they had signed up for, nor details about their prospective employers. Unbeknownst to them, their Iqama[vi] had been provided by a Saudi Arabian recruiting agency that then contracted out their labor to different households for the duration of their stay. Employers provided full up-front payment of the recruitment costs to the recruiting agency who then facilitated the process. The decision to not take part in the government’s mandatory training for housekeepers moving to the Middle East, in particular, severely impacted their experience in Saudi Arabia.[vii]

Having migrated without any knowledge of Saudi customs, language, or the type of work they had to carry out, all of the women ended up returning to Bangladesh a few months into their jobs. On average, the women who were interviewed held their positions for less than nine months. They reported instances of physical and verbal abuse from employers, extremely poor working conditions, and long working hours. A number of women also reported that employers regularly withheld wages and deducted their living expenses from their wages.

“I thought I would be doing the same work as I was then (working in other people’s homes). If I was able to earn almost ten times what I did, it was of course something I was interested in. The dalal did not tell me about any specific training that I needed to do. He simply told me that I needed to pay BDT 50,000 ($455) and he would take care of everything.”

– Sonia, returnee migrant

Due to the nature of the recruitment system in Saudi Arabia, workers are directly tied to their employers who sponsor their visas. As a result, the women were not able to freely move between jobs and had to depend upon the recruitment agency to switch jobs. In most cases, recruitment agencies did not accommodate requests from the women to change their jobs.

Having no support networks in the destination country, the women were forced to seek further financial support from their families in Bangladesh. In instances where the women would fall sick from the long working hours, their employers would simply transport them to the hospital and leave them to pay for their medical bills. Some women took the bold step of fleeing from their employers’ homes and handing themselves over to the authorities for eventual deportation. Eventually, they had to seek money from their families to pay for treatment or to arrange return flights back to Bangladesh. All of the women returned empty-handed and indebted further.

“When I asked for my monthly wages, they said they would pay it to me only after they had completely deducted the amount they spent to bring me here. I ended up working for nothing for six months. They would add my food costs and telephone bills to the due amount, and each month the amount kept getting larger and larger.”

– Sampa, returnee migrant

The Challenges to Reintegration

Upon their return, the women were faced with the challenge of repaying the debt they had accrued while facing significant ostracism from society and their families. Winrock’s Ashshash[viii] project provided support to the women for their social and economic wellbeing to assist in their reintegration. However, the underlying vulnerability that led them to migrate is still present. The financial precarity persists, despite having been linked to income opportunities through vocational training programs. Problems such as the rising cost of goods, rent, and access to safe drinking water continue to plague the lives of the women and their families. None of them foresee a way back to their villages.

Author: Ahmad Ibrahim (Program, Research, and Knowledge Management Advisor)

Facilitation: Ahmad Ibrahim, Zakia Naznin (Senior Technical Lead, Climate Change) & Abdul Gaffar (Senior Manager – Monitoring, Evaluation, Results, and Learning)

This case study was funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State.

[i] Hussain, N. , Islam, M. and Firdaus, F. (2018) Impact of Tidal River Management (TRM) for Water Logging: A Geospatial Case Study on Coastal Zone of Bangladesh. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 6, 122-132. doi: 10.4236/gep.2018.612009.

[ii] Choudhury, Abida Rahman, ‘The Water Benders of Satkhira’. The Daily Star. Last modified – December 21, 2018. Link – https://www.thedailystar.net/star-weekend/environment/news/the-water-benders-satkhira-1676515

[iii] One key point mentioned by the respondents was the added pressure of having to purchase everything that was required for consumption. Whereas previously, respondents said they were able to grow a number of consumption items within their homestead.

[iv] Colloquially, a dalal refers to a facilitator that connects individuals to different types of services, particularly in the case of government services, in return for payment. Dalals are not endemic to the migration process in Bangladesh, but are a class of intermediaries across various branches of society.

[v] Ara, Arafat. ‘Cost-free hiring of women by overseas recruiters ‘mismanaged’’, The Business Standard, Last modified – 23 October, 2021. Link – https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/trade/cost-free-hiring-of-women-by-overseas-recruiters-mismanaged-1634957558

[vi] Arabic term for work permit

[vii] The Bureau of Manpower Employment and Training (BMET) runs a 28 day residential course for women who will migrate to the Middle East for domestic worker jobs. This training is available a number of districts and is subsidized by the BMET. BMET rules, drafted in 2007, make it mandatory for all workers to complete this training before departure. However, dalals often find ways to forge certificates.

[viii] Ashshash – For Men and Women Who Have Escaped Trafficking is a project funded by the Embassy of Switzerland in Bangladesh and provides a range of different services to identified survivors of trafficking. This includes psychosocial assistance, vocational training and either job placements or business development support.