The Log Blog

When a tree falls in the forest, Winrock measures the emissions it leaves behind.

By Gabriel Sidman, Spatial Analyst

When a tree falls in the forests of Colombia, it does make a sound — a loud one — but only for a moment. The sound starts with the monotonous drone of a chainsaw, cutting the thinnest of wedges near the base of the tree, followed by a piercing crack as the saw cuts deep enough to break the tree apart. Then something like a groan fills the forest as the heavy tree falls to earth, snapping branches and uprooting nearby trees. Finally comes a soft rustle as leaves and twigs that once swept the sky settle into their new home on the forest floor. Soon, the ever-present sound of buzzing insects and chirping birds once again fills the forest, and the only evidence of the thunderous tree fall is a daylit hole in the canopy.

Selective logging in tropical countries such as Colombia can seem remarkable one moment and hardly noticeable the next. Removing just a few trees may not cause a drastic change in the landscape because new vegetation quickly hides evidence of a felled tree. But carbon is heavily concentrated in the giant trees, and once they’re felled and begin to decompose they emit greenhouse gases.

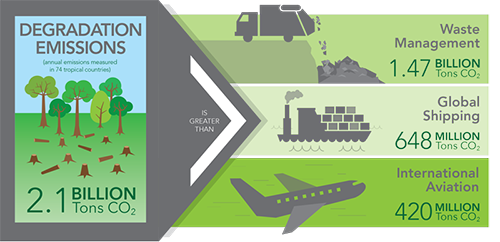

These emissions contribute to climate change in a way that is just beginning to be understood. We already know that in 74 tropical countries, 2.1 billion tons of carbon are released through forest degradation each year, a number larger than the total emissions from all but the world’s three largest emitters (China, the U.S. and India) and far more than the 420 million tons of emissions that come from international aviation every year.

To understand the impact of emissions from selective logging and attempt to reduce them, it is first important to find a way to reliably quantify and monitor the emissions. Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (IDEAM) has made some progress toward monitoring forest degradation in many parts of the country. Thus far, IDEAM has worked mostly with satellite images (often called remote sensing) to measure the impact of forest degradation. But satellite imagery, commonly used to expose clear-cutting of forests, does not detect selective logging as easily, given that changes in the landscape are less drastic. “In IDEAM we have generated information related to forest degradation using remote sensing, but only have achieved preliminary results,” explained Juan Pablo Ramirez, a senior researcher with IDEAM’s System for Forest and Carbon Monitoring.

To understand the impact of emissions from selective logging and attempt to reduce them, it is first important to find a way to reliably quantify and monitor the emissions. Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (IDEAM) has made some progress toward monitoring forest degradation in many parts of the country. Thus far, IDEAM has worked mostly with satellite images (often called remote sensing) to measure the impact of forest degradation. But satellite imagery, commonly used to expose clear-cutting of forests, does not detect selective logging as easily, given that changes in the landscape are less drastic. “In IDEAM we have generated information related to forest degradation using remote sensing, but only have achieved preliminary results,” explained Juan Pablo Ramirez, a senior researcher with IDEAM’s System for Forest and Carbon Monitoring.

To help address this problem, Winrock International’s Ecosystem Services team recently sent Blanca Bernal, Anna McMurray and myself to Colombia as part of a project funded by the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany under the International Climate Initiative to train in-country stakeholders in a unique methodology designed by Winrock to estimate and monitor selective logging emissions. Together with Ramirez and other IDEAM staff, we visited the Amazon rainforest in southeastern Colombia, then moved west to the Pacific forests of Urabá to demonstrate the methodology.

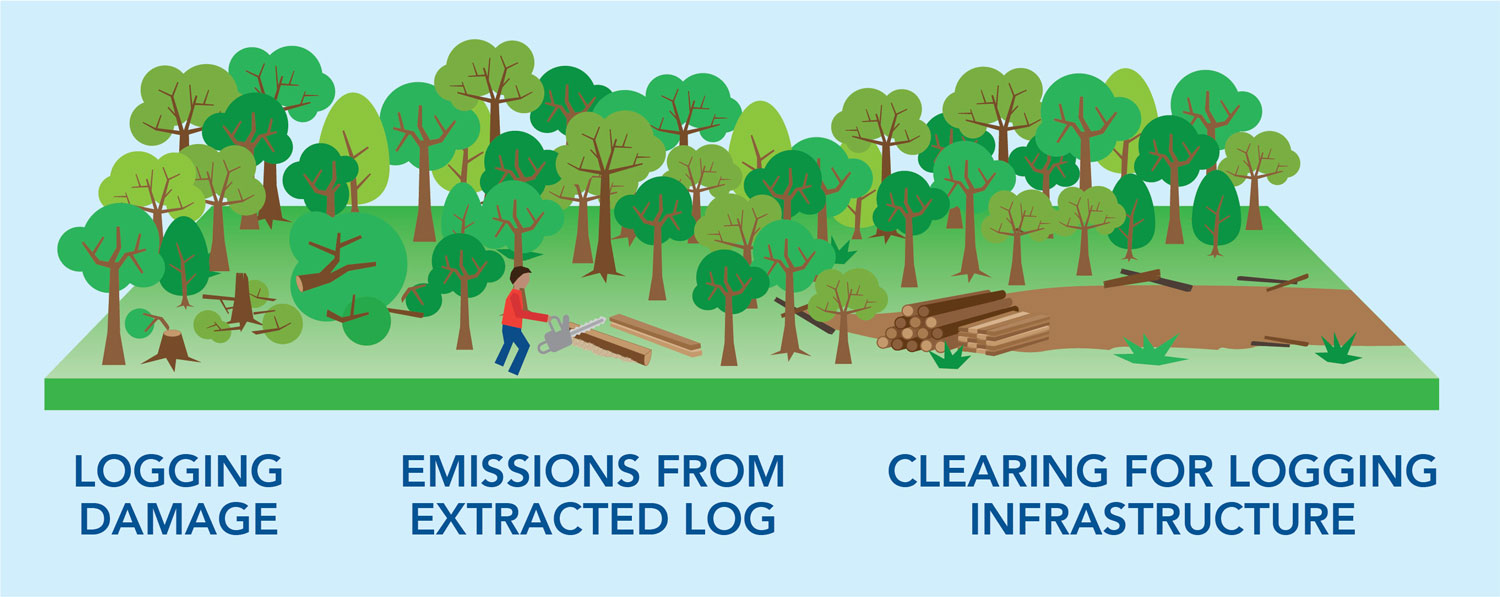

Winrock considers three types of emissions from selective logging. The first includes the emissions from the extracted log itself: the portion of the tree that is removed and sent to a mill to be trimmed, shaped and turned into finished products such as wooden furniture and building materials. This milling process creates sawdust and odd unusable pieces of wood that are thrown out and ultimately decompose. The second type of emissions is from the damage caused by felling the tree. This includes the stump and crown of the tree, which are left in the forest to decompose along with the nearby trees that were dragged down with the timber tree. The third factor is the clearing of the forest to make way for logging infrastructure, such as roads and decks to stack the logs.

Tracking the magnitude of all these emission types involves performing in-forest measurements, ideally carried out by local experts who understand their forest and can be quickly deployed for monitoring. This is why in-country trainings are so necessary — to bring this methodology to stakeholders living in the Amazon and Urabá.

Tracking the magnitude of all these emission types involves performing in-forest measurements, ideally carried out by local experts who understand their forest and can be quickly deployed for monitoring. This is why in-country trainings are so necessary — to bring this methodology to stakeholders living in the Amazon and Urabá.

In the Amazon we teamed up with staff from Corpoamazonia, a regional natural resource management authority in charge of tracking the flow of wood cut in the region. In Urabá, we involved Corpouraba, a similar management authority. In both locations, community members were involved in the trainings as forest guides and to help us understand the local logging practices.

Each day, we pulled on our rubber boots and rain jackets and headed into the forest, sometimes trudging through downpours along muddy trails and over precarious log bridges. At other times, we boarded wooden peque-peque boats to paddle down narrow rivers, ducking our heads to avoid overhanging branches. We visited stumps of recently cut trees where we pulled out measuring tapes, wrapping them around trees just above their buttressed roots or pulling the tape along the ground to measure the space where a log had been cut and removed. Often, we felt like detectives, piecing together the story of a felled tree: Where was the fallen crown? How did these discarded pieces of wood fit into the absent tree?

Each day, we pulled on our rubber boots and rain jackets and headed into the forest, sometimes trudging through downpours along muddy trails and over precarious log bridges. At other times, we boarded wooden peque-peque boats to paddle down narrow rivers, ducking our heads to avoid overhanging branches. We visited stumps of recently cut trees where we pulled out measuring tapes, wrapping them around trees just above their buttressed roots or pulling the tape along the ground to measure the space where a log had been cut and removed. Often, we felt like detectives, piecing together the story of a felled tree: Where was the fallen crown? How did these discarded pieces of wood fit into the absent tree?

The community members were the best detectives. The members of Corpoamazonia and Corpouraba were experts in tree measurements and identifying tree species. The IDEAM staff had the broader knowledge of how local logging practices compared to those of other locations in Colombia. Bringing these stakeholders together to understand Winrock’s cohesive emissions accounting methodology helped achieve a critical goal in conservation: connecting national and regional governments with community members to embrace problem-solving together, rather than in isolation.

The community members were the best detectives. The members of Corpoamazonia and Corpouraba were experts in tree measurements and identifying tree species. The IDEAM staff had the broader knowledge of how local logging practices compared to those of other locations in Colombia. Bringing these stakeholders together to understand Winrock’s cohesive emissions accounting methodology helped achieve a critical goal in conservation: connecting national and regional governments with community members to embrace problem-solving together, rather than in isolation.

As we wrapped up the trainings with time in the classroom learning how field measurements could be used in formulas to calculate emissions, the value of creating connections became clear. Winrock’s methodology provided a way to allow local stakeholders to take control of their own monitoring (often termed community-based monitoring), with community members working in tandem with regional management authorities to carry out field measurements. IDEAM can provide support and gather data from all over the country to estimate emissions at the national level, so that instead of analysts in the capital city of Bogota studying satellite images, members of the Amazon and Urabá communities are empowered to monitor their own land, creating trust that may have been lacking in the past. “Through these trainings we can strengthen the links with the regional management authorities and strengthen forest degradation monitoring,” said Ramirez.

As for the members of Corpoamazonia and Corpouraba and community members, they saw the trainings as a way to understand the impact logging was having on their forest and to learn about potential improvements. “This methodology can help us by making recommendations to use more of the wood and leave less in the forest,” said Alipio Chaverra of Corpouraba’s Department of Forest Control. “Perhaps we could use a wheelbarrow or cart to haul larger trunks of wood out to the rivers. This would lower the amount of wood left to rot.” A local logger in the small community of Tarapacá, Amazonas, offered a final opinion of the training: “Before, when we heard conservationists were coming to inspect our work, we used to tell them to go away, knowing they were just coming to tell us to stop logging. This time though, we were included, and we learned to log in a manner that causes less damage to the forest. This time, I feel that things are different.”

As for the members of Corpoamazonia and Corpouraba and community members, they saw the trainings as a way to understand the impact logging was having on their forest and to learn about potential improvements. “This methodology can help us by making recommendations to use more of the wood and leave less in the forest,” said Alipio Chaverra of Corpouraba’s Department of Forest Control. “Perhaps we could use a wheelbarrow or cart to haul larger trunks of wood out to the rivers. This would lower the amount of wood left to rot.” A local logger in the small community of Tarapacá, Amazonas, offered a final opinion of the training: “Before, when we heard conservationists were coming to inspect our work, we used to tell them to go away, knowing they were just coming to tell us to stop logging. This time though, we were included, and we learned to log in a manner that causes less damage to the forest. This time, I feel that things are different.”

Related Projects