The World’s Forgotten Forests: Stable Forests as a Climate Solution

Remote forests offer one of our best defenses against climate change.

Ecosystem Services team members Sophia Simon, Senior Analyst; Meyru Bhanti, Analyst, GIS; and Michael Netzer, Technical Lead, GIS

Forests truly are the lungs of our planet. They absorb massive amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) and release oxygen (O2). Their protection is vital to regulate our climate, but also to maintain biodiversity, filter and regulate water, and form the soil and clouds that feed our fields and pastures. At the U.N.’s 2021 Climate Change Conference (COP26) in November 2021, countries pledged to provide $12 billion in forest-related climate finance between 2021 and 2025 and signed a landmark agreement to end deforestation by 2030.

However, what many people may not know is that global market mechanisms to save forests have historically focused on forests on the margin – those forest areas that are directly in the path of the bulldozers and are most imminently threatened by degradation and deforestation. Meanwhile, “stable forests,” which are remote, old-growth forests untrammeled by human feet and make up 16% of this global lung, remain highly vulnerable. While good reasons exist to first focus on threatened forests, if we forget to value these remote wildwoods too, we lose an important incentive for countries and regions to harbor what is left.

An article in the journal Climate Policy by Jason Funk, Naikoa Aguila-Amuchastegui and others defined stable forests as “those not already significantly disturbed nor facing predictable near-future risks of anthropogenic disturbance.” These well-preserved forests are some of the richest in biodiversity and other ecosystem services – the various benefits to humans and other life provided by the natural environment ─ and are a vital solution to climate change. Yet they have not been historically included as eligible to participate in the vast majority of market-based solutions and schemes designed to protect and restore global forests. Forest policy that incentivizes protecting only areas at high or immediate risk of loss is akin to funding only emergency care in hospitals, while ignoring preventative health care for the broader community.

Value of global stable forests

In July 2020, a team of Winrock analysts alongside Professor Brent Sohngen and policy expert Robert O’Sullivan began a project to analyze stable forests funded by the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility at the World Bank. Our goal was to determine the global distribution of stable forests, quantify their worth, and develop strategies to best protect them.

In our spatial analysis, which built on research already published by Funk et al., as well as studies of intact forests and other work, we defined stable forests as those: a) With tree canopy cover greater than 25%; b) At a distance of at least 1 kilometer from the forest edge; and c) With a low-to-moderate Global Human Footprint Index (of less than three). We classified any forests that didn’t fit these criteria as at-risk.

We found that stable forests cover 625 million hectares, representing 16.6% of all global forests. Almost all stable forests (88%) are in the tropics, making this region a key policy priority (see our story map for more results, including case study countries).

These forests store approximately 140.9 gigatonnes of carbon, a huge reserve that is almost 11 times more than all annual global carbon emissions. They remove an additional 416 million tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere per year – or almost as much as annual emissions from the entire global waste sector, all of Brazil’s annual emissions, or double the total amount of Canada’s emissions in 2018.

And stable forests aren’t only valuable for their incredible carbon removal capacity. They also provide immense benefits to humankind by regulating climates, providing food, filtering waterways, and enriching cultures. Valuing stable forests is a crucial step in making a range of financial and policy mechanisms available to better protect them. If we consider and quantify the value of just three other ecosystem services provided by forests in addition to carbon removal (biodiversity, non-timber forest uses, and hydrology), the value of stable forests in the tropics, alone, tallies a tremendous $4.9 billion.

Carbon markets, results-based payments, and stable forests

Carbon markets for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) have been predominantly led by projects based on “avoided deforestation,” with their value based on the value of what would have otherwise been lost, and bilateral and multilateral results-based payments approaches for REDD+ have focused at the jurisdictional level on efforts to reduce deforestation. However, stable forests, due to their remoteness, have very low rates of deforestation. If we only value them based on the current threat of deforestation, the annual loss of tropical forests would stand at $5.7 billion – or just 0.12% of their actual value, to use the $4.9 billion figure cited above. Conservation of stable forests, therefore, has not been incentivized under these approaches.

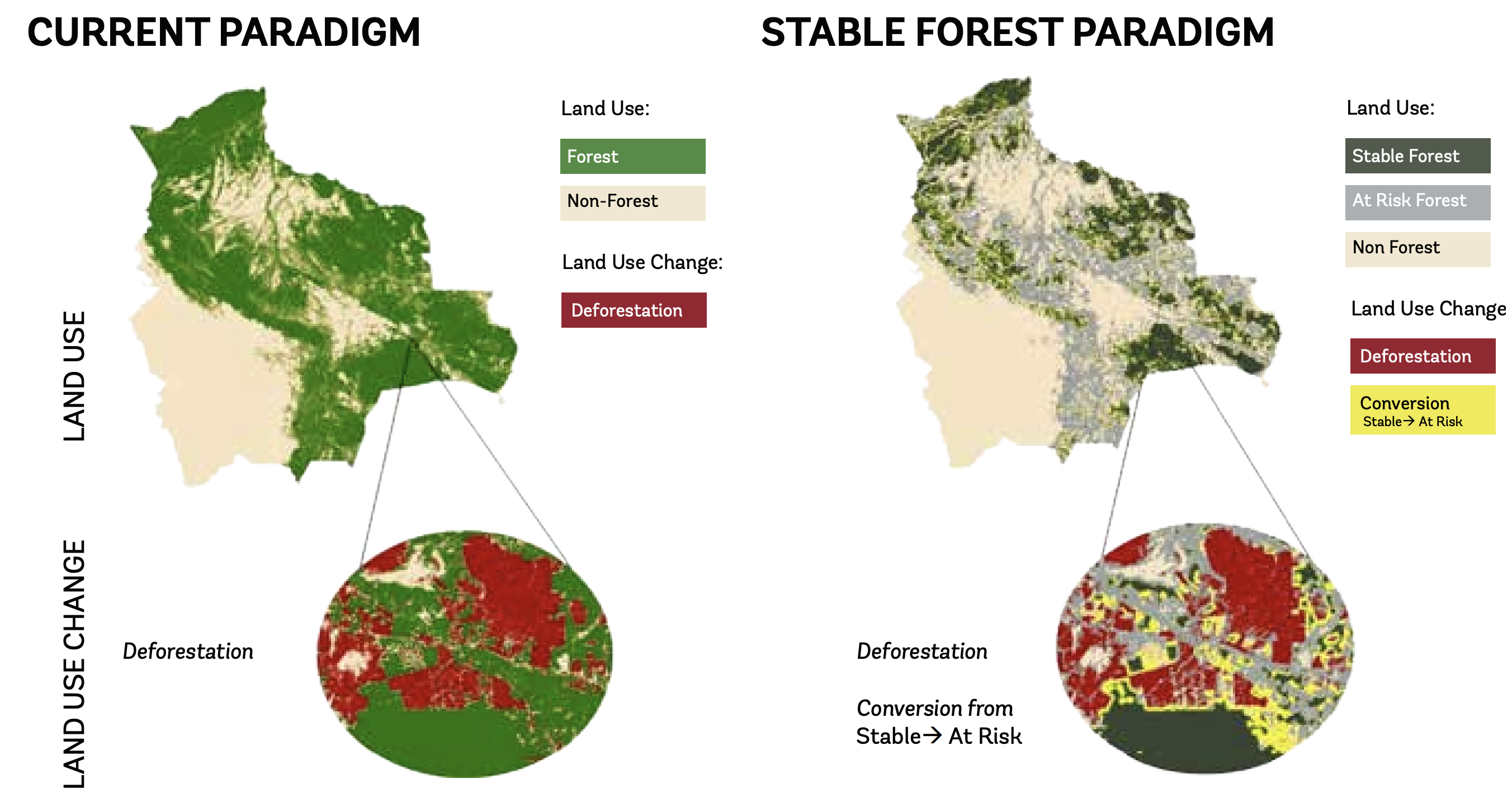

Our analysis makes clear the need for a paradigm shift in how we evaluate forest change. Despite historically low deforestation in stable forest areas, over the last decade (2010-2019), 20.6% of stable forests were identified as transitioning to a higher risk of fragmentation, degradation, and ultimately, deforestation. In other words, they were converted from stable to at-risk forests.

Conventional approaches to evaluating forest cover overlook that transition (see figure below), while the stable forest paradigm highlights it. This novel paradigm promotes preventative action to conserve all forests by stopping the initial conversion from stable to at-risk forests, maintaining forests in a healthy, threat-free condition for the long term.

The annual resources needed to prevent conversion and to ensure that the services provided by stable forests do not decline is estimated to be $177 billion per year. This “maintenance value” price tag could be a new way to help drive financing and protection of stable forests.

Moving forward: protecting stable forests with policy solutions

To protect stable forests, we first need to focus on domestic policy and governance, for which solutions should be tailored to national circumstances. Domestic funding – both public and private – can be mobilized by either increasing the costs of damaging stable forest through subsidy reforms, for example, or by creating additional revenue linked to forest protection through ecological fiscal transfers or payment for environmental services. Countries with especially weak governance could (and should be) encouraged to focus on improved forest governance to control illegal activities along with fiscal reform over other policy options, such as designing market-based protection mechanisms or attracting green finance.

Another possible solution, as we note in the World Bank report, Options for Conserving Stable Forests, is to develop a crediting mechanism for stable forests, which would support the goals of the Paris Agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and domestic policy. The annual “maintenance value” of stable forests (including a range of ecosystem services in addition to carbon, which could vary based on national priorities) could serve as a benchmark for the value of the credits, ultimately incentivizing the continued protection of stable forests.

Note that since the publication of the report for the World Bank, Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART), for which Winrock serves as the Secretariat, released TREES 2.0, an enhanced and expanded version of its standard for measuring, monitoring, reporting and verifying emission reductions from jurisdictional REDD+. TREES 2.0 includes an innovative crediting approach for jurisdictions – both national governments and subnational areas including Indigenous Peoples territories – that is intended to incentivize the protection of intact forests. TREES 2.0 addresses these intact forest areas that have high forest cover and low levels of deforestation (also known as High-Forest, Low Deforestation (HFLD) jurisdictions) through a flexible, dynamic scoring mechanism for crediting that takes into consideration the unique characteristics of HFLDs, specifically the percent forest cover and the deforestation rate. Through the HFLD approach, TREES 2.0 aims to incentivize jurisdictions to protect intact forests, since guarding the carbon sequestered in these forests is essential to meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement.

To link to the Winrock story map click here; to link to the World Bank report click here.