When Improving America’s Infrastructure, Don’t Forget Forests

This Infrastructure Week, we should remember to focus on growing, restoring and preserving our nation’s natural infrastructure.

America’s water infrastructure is in a state of disrepair, as evidenced by disasters such as the public health crisis in Flint, Michigan and dangerous flooding at the Oroville Dam.

While water infrastructure like treatment facilities, flood control systems, pipes, wastewater treatment plants and reservoirs are essential for public health and safety, our current, aging systems are inadequate for today’s needs. For example, in order to fulfill the growing demand for safe drinking water in the United States, the million-plus miles of water pipes across the country will require $1 trillion in investments over the next 25 years.

Across party lines, a growing chorus is calling for urgent action to address current infrastructure shortcomings. These voices are rallying together for Infrastructure Week, a time for U.S. government, industry groups and nonprofits to confront issues faced by our nation’s roads, sewage systems, energy grids and more.

Infrastructure Week’s motto, “It’s #TimeToBuild,” emphasizes traditional, engineered systems. But ramping up water infrastructure means looking beyond building new pipes and pumps. While traditional, “gray” infrastructure is essential, we also must focus on growing, restoring and preserving our nation’s “natural infrastructure,” such as forests.

Are Forests Infrastructure?

Infrastructure consists of the physical structures and facilities that society and enterprises need to operate. This brings to mind built structures such as roads and pipes, but society requires forests, wetlands and other natural landscapes as well. These systems, our “natural infrastructure,” provide many of the same services as built infrastructure, such as protecting against extreme weather and temperatures, and supplying clean water.

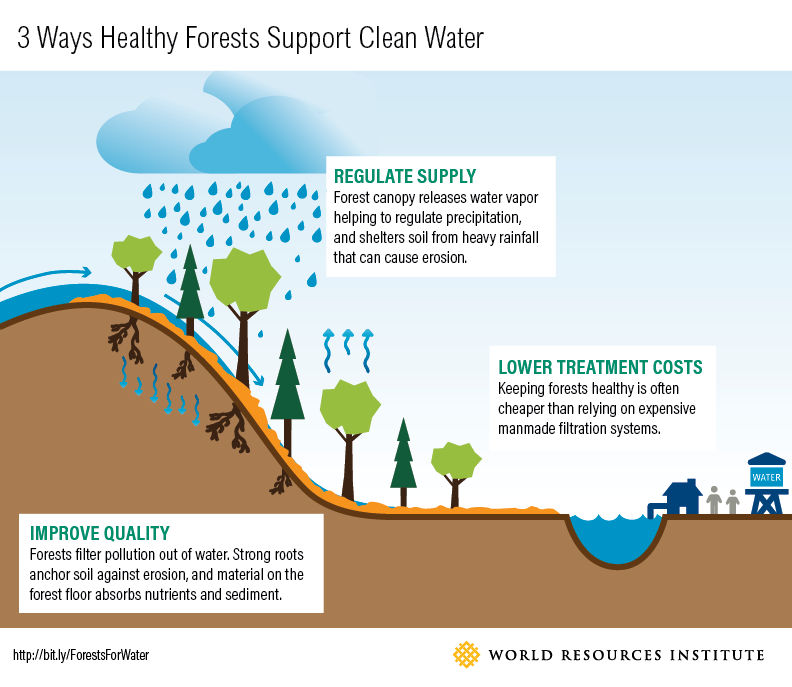

Forests are a natural form of water infrastructure, as they can mimic a water storage reservoir, flood control system and water treatment plant at the same time. Forests can act as a sponge, absorbing rainwater during storms, which reduces flooding. They can then slowly release water during dry periods, helping combat water scarcity. The complex root structures of a healthy forest hold soil in place to control erosion and absorb nutrients that cause water pollution. The very water that comes from your tap may have been filtered by a forest: About 180 million people across 68,000 communities in the United States rely on forests to collect and clean their drinking water.

Natural systems also have unique benefits that make them immune to some of the pervasive issues facing America’s built infrastructure:

- The value of a forest appreciates over time as it grows and matures—unlike built infrastructure, such as pipes and reservoirs, which ultimately need costly repairs or complete replacement.

- Forests provide benefits beyond supplying clean water, such as carbon sequestration, habitat provision and recreation opportunities.

- Forests and wetlands build resilience for surrounding built infrastructure systems by absorbing floodwaters and providing a buffer against storm surges. This extends the life of built systems and boosts their capacity to endure climate change and weather extremes.

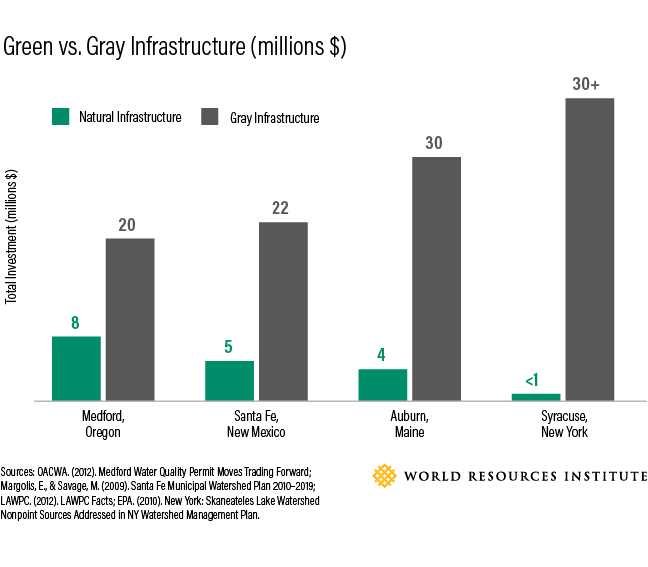

Finding money to repair and upgrade water infrastructure is a huge challenge. Investing in forests can be a cost-effective strategy to reduce these costs. In the late 1990s, New York City invested $1.5 billion to protect the forests that filter their water naturally. This allowed the city to forego building and maintaining a new filtration plant, which would have cost $8-10 billion.

Other cities that have invested in natural infrastructure have found similar success: Six U.S. cities with excellent water quality managed to save anywhere from $500,000 to $6 billion in water treatment costs by investing in sustainable forest management.

Gray Needs Green

Water managers can also see benefits by using green and gray infrastructure in tandem. In a green-gray approach, forests are used to safeguard conventional water infrastructure systems, and provide downstream water utilities with cleaner, plentiful water that requires less treatment.

WRI studied 13 cities taking this approach: San Francisco’s Public Utilities Commission dedicated about 10 percent of its massive $240 million wastewater infrastructure bond specifically for green infrastructure. In Central Arkansas, water users pay an extra 45 cents per meter per month on their water bill for watershed protection. While the majority of ratepayers’ overall contributions go to operating and maintaining the built infrastructure system, approximately $1 million per year goes to protection of natural infrastructure upstream of the water treatment facility. Protecting the source watershed ensures the provision of clean water to the utility, while maintaining the built infrastructure system allows this water to be distributed effectively to customers.

Forest Trends found that as many as 45 cities in the United States invest in forest protection and restoration upstream of their water treatment facilities in order to protect water quality.

Across America, It’s Time to Grow, Restore and Build

Despite a growing awareness of its benefits, natural infrastructure is still rarely a priority in our domestic infrastructure portfolio. That’s why WRI is developing tools and approaches to identify where and how investments in nature can improve infrastructure performance at lower costs.

Our nation’s infrastructure needs help – but we can’t focus on gray infrastructure at the exclusion of forests, wetlands and other natural landscapes. This Infrastructure Week, remember that infrastructure means more than just building – it includes growing and restoring, too.

This post originally appeared on the World Resources Institute website.

Betsy Otto is the Director of WRI’s Global Water Program. Over the past several years at WRI, she has led development of Aqueduct™, a global water risk assessment and mapping tool to inform private and public sector investment and water management decisions. Betsy works with the Water Program team to develop and apply tools and information, and to engage business, NGOs and governments for positive change in managing water resources worldwide. Betsy also works with staff across WRI to incorporate water considerations and sustainable solutions for cities, energy, governance, finance, and climate adaptation purposes.

Suzanne Osment is an Associate II with World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Global Water Program, where she researches the design of profitable strategies to protect and restore watersheds. As member of WRI’s Natural Infrastructure for Water team, she works with business, financial institutions, and conservation organizations to scope out smart investment opportunities to protect and restore watersheds, and to advance policies that enable strategic watershed management.

Header image: Natural infrastructure like healthy forests can support clean water. Photo by Adirondack Watershed Institute/Flickr.

Related Projects