Winrock ECO Pilot: EPcs used consistently by low income households in peri-urban nepal

Winrock program officers Govinda Khanal, Rabin Shrestha and Loughborough University's Richard Sieff publish a guest blog through Modern Energy Cooking Services on March 22, 2022.

Winrock program officers Govinda Khanal, Rabin Shrestha and Loughborough University's Richard Sieff publish a guest blog through Modern Cooking and Energy Services on March 2, 2022.

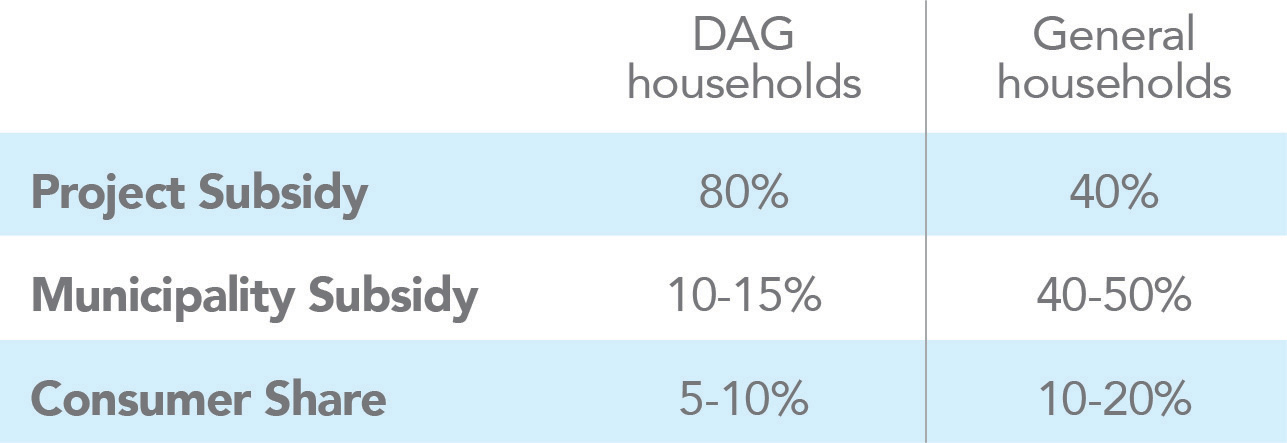

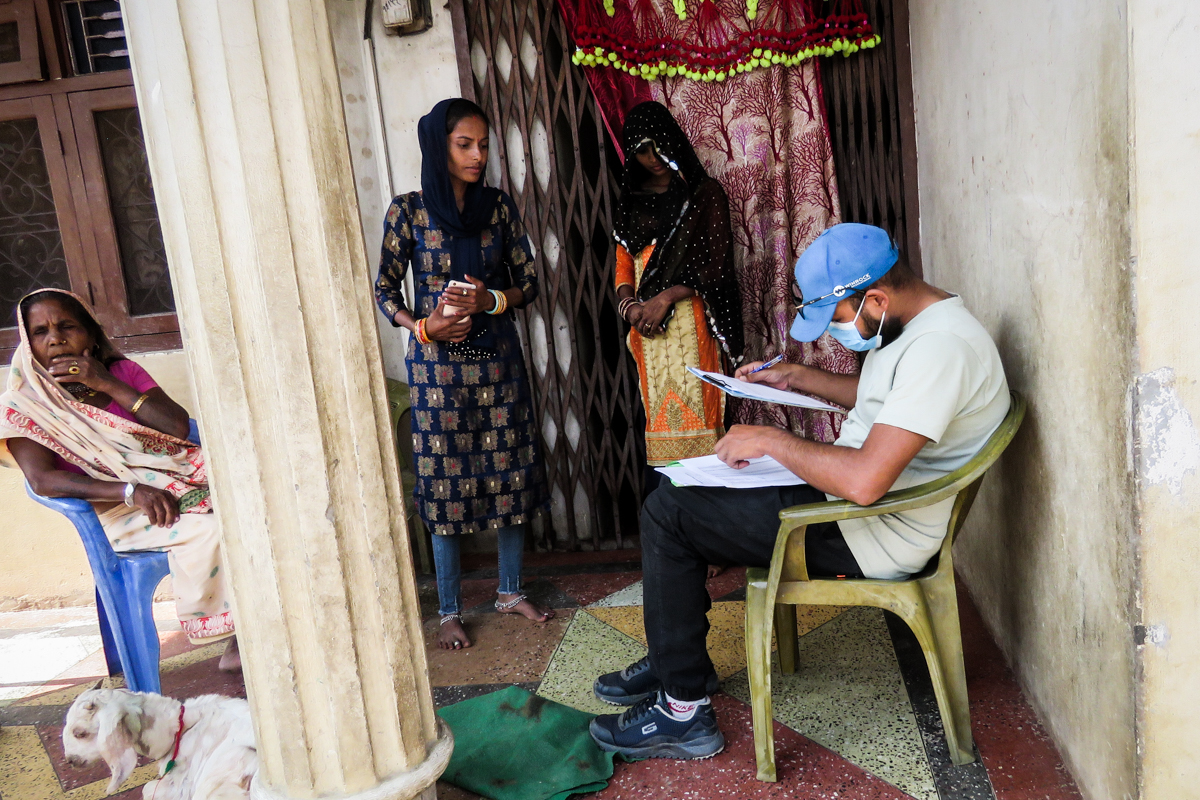

While transitions to electric cooking (eCooking) in more affluent and urban Nepali communities have been documented, a recent MECS Electric Cooking Outreach (ECO) challenge fund pilot study in Nepal has demonstrated clear uptake of eCooking by low-income peri-urban households – even those which collect firewood for free. Fifty households in Katahariya Municipality (Rautahat District) participated in the six-month pilot which assessed whether electric pressure cookers (EPCs) were compatible with consumer preferences and the local electricity infrastructure. Twenty households from disadvantaged groups (DAGs) – either ethnic minorities or economically poor – were included to see how eCooking preferences and uptake compared with the 30 non-disadvantaged households (“General group”). The study was conducted by the non-profit organization, Winrock International, with project partner, the Renewable Energy, Water Supply and Sanitation Promotion Centre (REWSSPC).

Sizeable eCooking uptake mainly replaces LPG

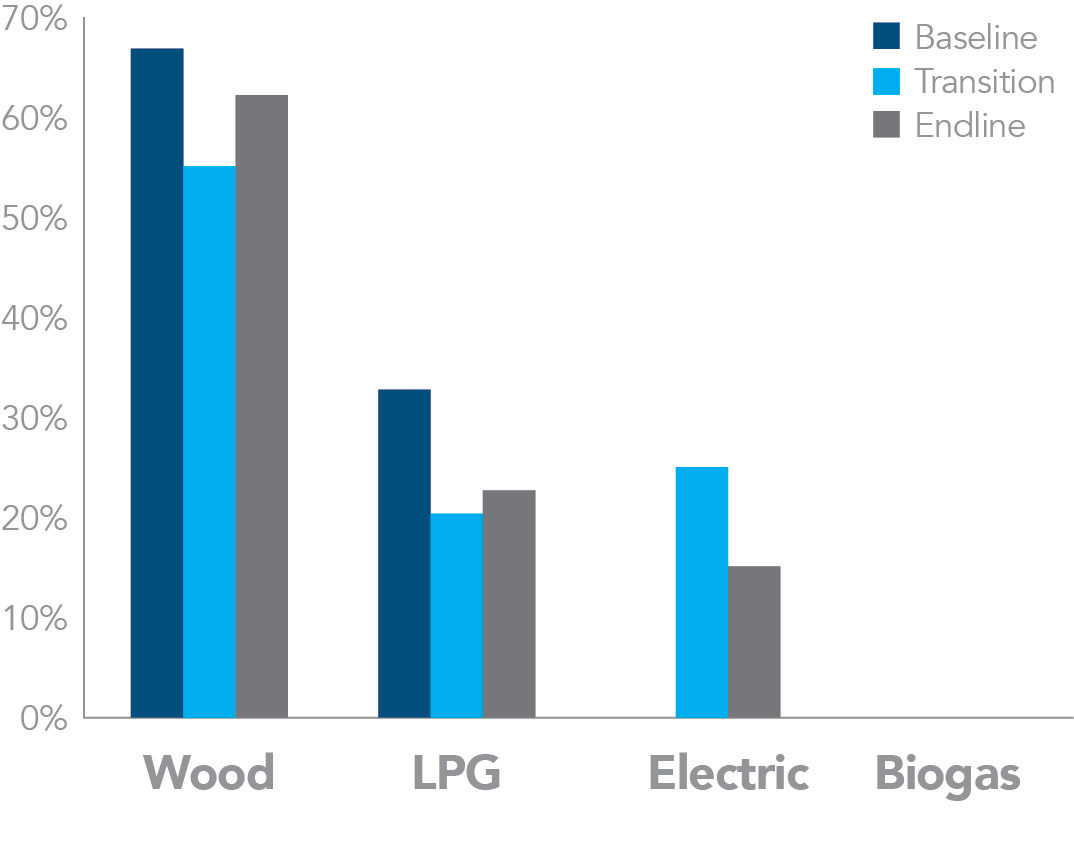

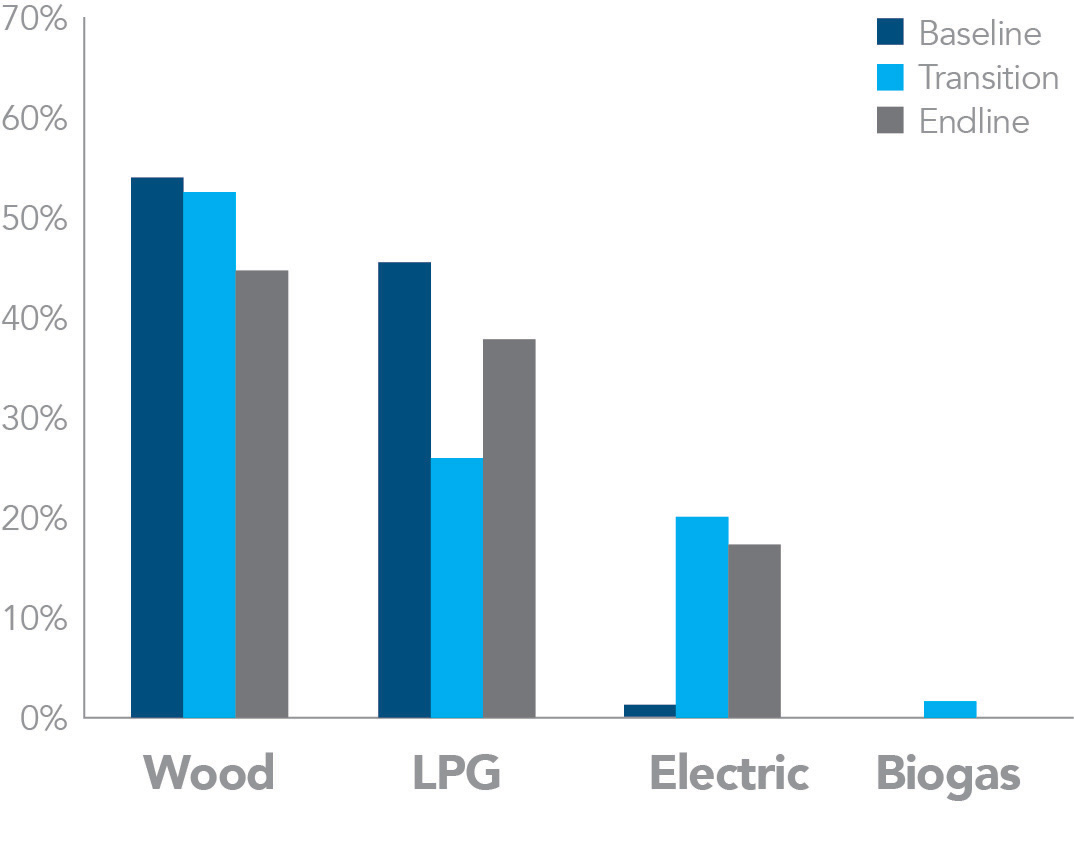

During the pilot, subsidized EPCs (Table 1) were distributed to the 50 households, with usage monitored through cooking diaries, energy meters and surveys. Once introduced in the transition phase (month 2), EPC use was sizeable and consistent in both groups. eCooking events increased from 0% to 25% in DAG households and from 0.7% to 20% in General households (Figures 1-2). After the transition phase, this share fell to a sustained 34% across both groups for the remainder of the pilot, with EPCs accounting for 15% (DAG) and 17.5% (General) of cooking events in the endline phase (two weeks of month 6). This reduction in use was primarily due to the lack of local service centres to repair EPC faults. The endline phase also coincided with a festival season where quantities of food were cooked that were beyond the capacity of the EPC, while firewood use increased in the last two (colder) weeks as some cooked with the fuel to heat their homes.

The uptake in eCooking led to LPG use reducing by 10% in DAG households and 8% in general households, with biomass falling by 5% (DAG) and 9% (General). Replacing more firewood proved challenging as it is mostly collected in the community (i.e. free). Electricity + firewood emerged as a common fuel stack, used consistently for 20% (DAG) and 15% (General) of meals. These findings suggest EPCs are likely to substitute the use of LPG more than firewood but are unlikely to completely replace other fuels.

EPCs prove a good fit for local cooking practices

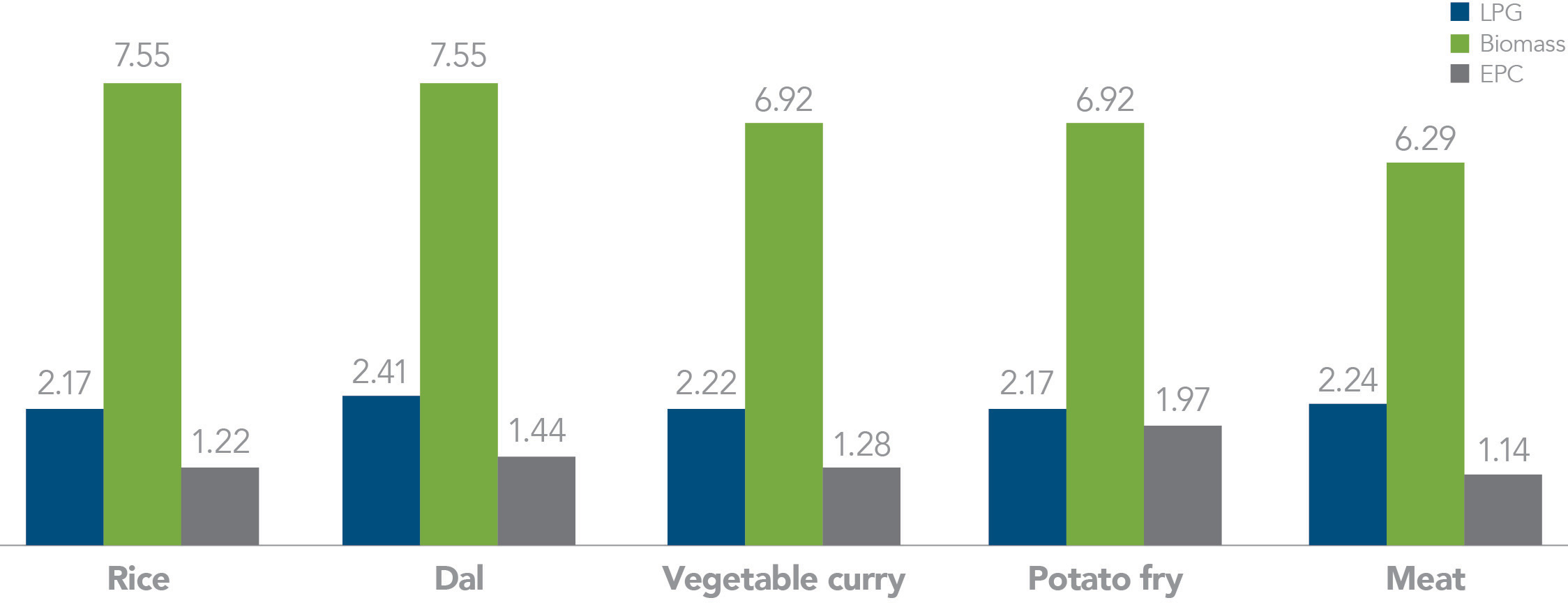

The foods people cooked changed little during the pilot, indicating eCooking suits the local cooking culture. Households particularly liked the EPCs for their ease of use, faster cooking times, and the taste of the food. The safety and cost savings of EPCs were also widely appreciated. EPC cooking costs were over five times cheaper than purchased firewood and approximately half those of LPG (Figure 3). These positive experiences resulted in almost all participants stating they would continue using the EPC post-pilot, while 50% indicated they would pay the retail price for a device (although disconnects between surveyed preference and reality are common).

EPCs were mainly used to cook rice and lentils with the lack of adjustable heat control (to speed up cooking) preventing some from preparing other dishes. The size of the EPC inner pot also limited use for larger households and 50% of participants requested an extra pot to cook multiple dishes without needing to empty the pot first. Whether an additional pot would encourage eCooking remains uncertain as the participants’ consistent use of double burners (stoves) over firewood or LPG (and sometimes firewood with LPG) suggests simultaneous, rather than consecutive, cooking of dishes may be preferred.

Local after-sales services the key to increasing eCooking uptake

To expand eCooking uptake, more reliable electricity and improved home wiring are required. Frequent power outages caused participants to revert to LPG or wood, while all households required wiring upgrades to enable eCook adoption. Upgrading meter connections could also facilitate increased use. While the participants’ 5 ampere connections proved sufficient for EPCs which do not draw continuous power (a key advantage for weaker grid infrastructure), 15-amp connections are required to run other eCook devices or multiple appliances simultaneously.

However, more pressing is the need to establish local service centres to cater for last mile repair and maintenance. During the pilot, five devices experienced technical issues and needed to be returned to Kathmandu for repairs under the warranty. Being poorly connected to the capital, the turnaround was lengthy (2-3 weeks) which undermined confidence in eCooking among participants who feared repairs would not be possible or challenging (especially post-pilot). These concerns were the main factor behind the reduction in EPC use (Figures 1-2) and potential scope for the more widespread electric rice cooker supply chain to provide EPC after sale services need to be explored.

Next steps: completing the jigsaw

The positive reception and use of the EPCs by DAG households further strengthens the existing body of evidence for eCooking in Nepal by clearly showing low-income households will choose to cook on electricty if appliances are made available. At this stage, the results show that the EPC enables a part transition to eCooking. To enable a greater shift, further research is required into how credit facilities might allow eCook devices to be more competitively priced while local service centres are urgently needed to increase household confidence in the technology. This need for decentralized after-sales services reinforces the importance of the ‘jigsaw concept’ at the heart of each MECS country-level theory of change, which highlights how all pieces of the (location specific) puzzle need to be in place to enable scaled uptake of eCooking.

This blog was originally posted on the Modern Energy Cooking Services website on March 22, 2022. For more information on this study, the Winrock ECO final report is available on the MECS website.

Related Projects