Launching a Specialty Coffee Movement in Myanmar

A Winrock Legacy Story

The call came one day after Rick Peyser had completed another marathon — this one, the fateful 2013 Boston Marathon. He crossed the finish line moments before a pair of bombs exploded, killing three and injuring several hundred. It would have been easy to turn down the caller’s request: Could you take leave from your job as Director of Social Advocacy at the largest organic coffee roaster in the U.S., travel 8,500 miles from Vermont to Myanmar, a country then led by a quasi-military regime, to conduct unpaid training exercises with several hundred coffee growers in remote locations?

Peyser didn’t even hesitate. He headed out on the assignment, which was made possible by the USAID-funded Asia Farmer-to-Farmer project, implemented by Winrock International from 2013 through 2018. Peyser didn’t know it at the time, but his arrival as the first Asia Farmer-to-Farmer volunteer to work on coffee in Myanmar would affect nearly every aspect of the way Arabica is cultivated, harvested, processed, marketed and even tasted in the once cloistered nation also known as Burma.

“My mission was to explore the coffee value chain in Shan State to determine if coffee could be a good option for the country and its small-scale farming families,” he later wrote about his assignment in an article for Roast magazine, an influential trade publication. Partly due to his recommendations, and partly due to the article he wrote for Roast, specialty coffee would rapidly evolve as a new, high-value crop for Myanmar smallholders, many of whom were beginning to ponder how to enter better-paying markets after decades of economic isolation.

In preparation for the Myanmar assignment, Peyser readied presentations covering everything from sustainable cultivation, processing and roasting, to the history of Green Mountain Coffee Roasters (his employer at the time), to an overview of the U.S. coffee market, the world’s largest. But in the end, a few pieces of advice, gleaned over decades of work with farmers in developing countries, would have the most impact: 1) get organized; 2) focus on quality; and 3) diversify.

“At the time, the small-scale farmers I met with were selling their coffee to Chinese buyers who offered a ‘take it or leave it’ price,” Peyser recalls. “They did not seek or pay for quality — they bought all coffee regardless of quality and paid a low price for it. When I met with a group of about 40 or so small-scale farmers, I encouraged them to organize so that they could better negotiate as a group.”

Encouraged by his insights into improved cultivation and processing, as well as market intelligence about expanding global demand for specialty coffee, farmers not only formed a producers’ group, but soon after Peyser’s visit they launched Myanmar’s first coffee-dedicated trade organization, the Myanmar Coffee Association.

Peyser and subsequent Farmer-to-Farmer coffee experts, along with more than two dozen other coffee agronomy, processing and trade volunteers deployed by USAID’s Value Chains for Rural Development project, implemented by Winrock and a Farmer-to-Farmer Associate Award, observed farmers’ practices and coached them on how to assess the characteristics and quality of their coffee through grading and cupping, making a series of transformative recommendations. Due to the relative lack of water in the highlands, for example, volunteers suggested farmers focus on sun-dried, natural processing methods instead of washed processing. Peyser noted that most Myanmar farmers were already “organic by default” – in other words, they were not using chemical fertilizers or other inputs, in part due to cost, but also because they were already skilled at making natural composts and tending their plantations with good plant spacing and shading. With a bit more attention to their trees and soil, as well information about combating common problems like coffee leaf rust, Myanmar’s coffee farmers began to improve yields and quality.

As better practices took root, the association and private sector firms developed a new culture of inclusive collaboration, organizing the first nationwide cupping competitions and other events featuring smallholders from various ethnic groups, as well as women producers and processors.

This approach ensured that all coffee farmers in Myanmar received access to training, marketing and leadership opportunities, resulting in the rise of new coffee entrepreneurs like Su Su Aung, now a leading processor and exporter of high-quality coffees exported to the U.S. and Canada. Su Su Aung’s company today counts coffee buyers from U.S.-based Whole Foods Market amongst its customers, while an expanding cadre of high-end buyers from the U.S. and more than a dozen other countries now make annual pilgrimages to Myanmar to scoop up the country’s best beans.

The result of this interest: increased exports of Myanmar coffee, rising from a few shipping containers in 2013 to nearly 240 tons worth $1.5 million exported in 2019, along with increased prices paid to farmers up to three times higher than previously. New ventures have sprung up, too, including a Nestlé -owned company now partnering with a women’s organic coffee group in the same hills Peyser first visited.

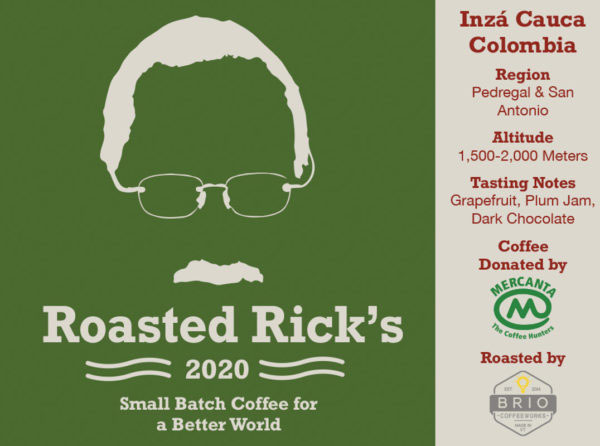

Peyser continues his more than 30 years of work helping coffee farmers as a board member and advisor to organizations that help farmers improve practices, access affordable financing and boost livelihoods. A co-founder of a nonprofit called Food for Farmers that supports smallholders in Colombia, Mexico, Nicaragua and Guatemala during the “lean season” between harvests, he was honored this year with a special-issue coffee blend, “Roasted Rick’s,” with all proceeds contributed to the organization.

Asked what has made his approach uniquely effective over the long haul, Peyser, who continues to run marathons, says, “I think and hope that the farmers that I worked with could see that my interest in serving was not transactional. I was genuinely interested in their success as farmers and as farming families. I was there to serve, not for personal gain — as I am sure all Farmer-to-Farmer volunteers are.”

Related Projects

Value Chains for Rural Development in Burma (VC-RD)

Increasing the productivity and profitability of smallholders in Burma has the potential to substantially improve food security and livelihoods in poor, rural communities. USAID’s Value Chains for Rural Development project uses an inclusive, market systems approach to support smallholder producers, farmer groups, agribusinesses and community organizations in the coffee, soybean, ginger, sesame and melon value…