From ADC Scholar to a Lifetime of Service in Nepal

By Chris Warren

By Chris Warren

Although he had always been a top student, there was one test Hari Upadhyaya desperately wanted to fail. As a young civil servant working for Nepal’s Department of Agriculture in the 1980s, Upadhyaya plotted out a career path that he hoped would include earning an advanced degree in agricultural science that he could use to help improve the lives of farmers in his native country. But his life took a sharp turn when his bosses ordered him to appear for an exam administered by the Agricultural Development Council (ADC).

Founded in 1954, ADC funded scholarships to support the studies of students focused on addressing the agricultural challenges faced by Asia’s rural poor. During its 31 years, ADC supported the advanced degrees of 588 scholars, who in turn made an enormous contribution to agriculture across Asia. ADC merged with two Rockefeller family organizations in 1985 to become Winrock International, although support for agricultural research continues under the banner of the John D. Rockefeller 3rd Scholars Program.

Though ADC’s mission meshed with his own, Upadhyaya balked at winning a scholarship because he knew it would fund studies in agricultural economics. “I thought economics is not a science,” he says. “The department ordered me to appear for the ADC examination and I had to agree. I prayed that I should fail.”

He didn’t. So Upadhyaya reluctantly went off to the University of the Philippines, where he earned his masters and Ph.D. in agricultural economics. In retrospect, he’s relieved he didn’t botch the exam. “It was a turning point,” he says. Not only did Upadhyaya quickly grasp the value of the economics he learned in the Philippines, he was certain the knowledge he brought home to Nepal would improve lives.

He didn’t. So Upadhyaya reluctantly went off to the University of the Philippines, where he earned his masters and Ph.D. in agricultural economics. In retrospect, he’s relieved he didn’t botch the exam. “It was a turning point,” he says. Not only did Upadhyaya quickly grasp the value of the economics he learned in the Philippines, he was certain the knowledge he brought home to Nepal would improve lives.

And that is exactly what Upadhyaya has been doing since arriving back in Nepal in 1985. “Dr. Upadhyaya is very influential in the agriculture sector and is one of the country’s top thought leaders,” says Jeff Apigian, a program officer at Winrock, who has long been involved with agriculture development work in Nepal. “He was selected as one of the best and brightest in Nepal and had that talent cultivated through the ADC and has gone back and make a big difference.”

Though he’s been an important voice in the shaping of Nepal’s agriculture policy, perhaps the biggest impact Upadhyaya made was by founding the Center for Environmental and Agricultural Policy Research, Extension and Development (CEAPRED), a Kathmandu-based NGO. Launched in 1991, CEAPRED works throughout Nepal on a range of agricultural and environmental issues, including managing natural resources, addressing climate change and improving the livelihoods of farmers by providing them training and knowledge to bolster their productivity and incomes.

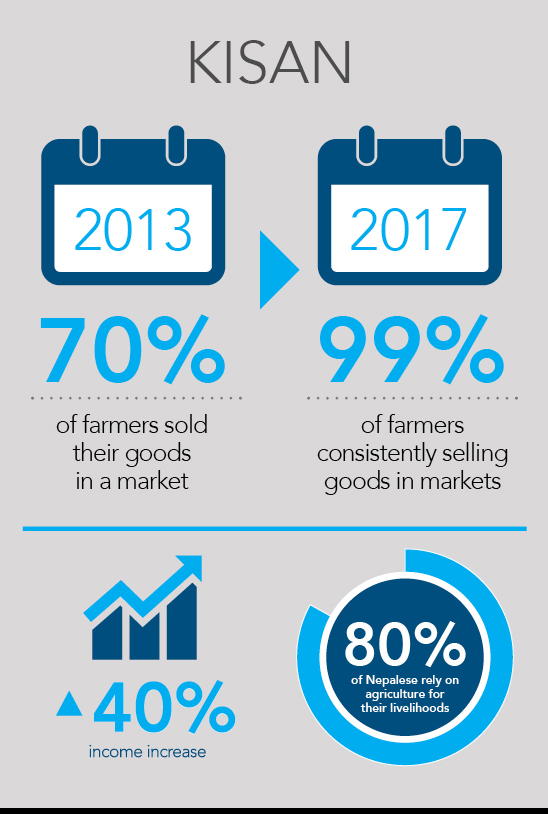

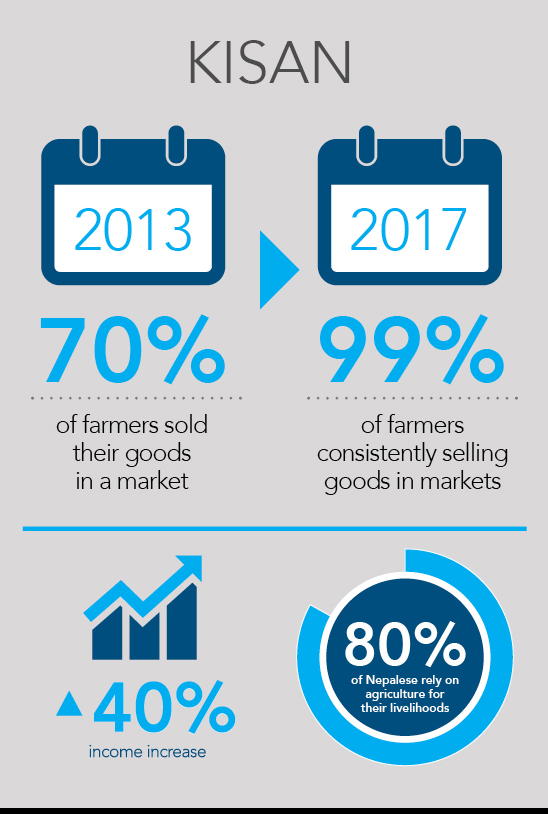

Given Upadhyaya’s connection to the ADC and CEAPRED’s underlying mission, it’s hardly surprising that his organization has forged a long-term alliance with Winrock. Most recently, CEAPRED has been a local partner in the Winrock-implemented and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded Knowledge-based Integrated Sustainable Agriculture and Nutrition (or KISAN, which means farmer in Nepali) project.

Upadhyaya knows from experience that the value chain approach KISAN utilizes represents an important departure from how development has traditionally been pursued in Nepal. Driven by the idea that free market principles can produce sustainable change, KISAN’s value chain approach improves farmer skills but also connects them to markets and providers of fertilizer and other inputs so that all can profit by working together.

And in fact, of the 103,835 farmers KISAN has trained in improved agricultural practices and technologies, 99 percent have applied these technologies and practices with significant results. Increased gross margins for target commodities are up by an average of 67 percent over baseline levels; gross margins for vegetables increased by an average of 74 percent over baseline. By convincing and then assisting farmers in making the jump from subsistence agriculture to commercial farming and by forging critical connections to markets, KISAN has lifted the average annual household sales of agriculture products by over 300 percent.

“KISAN is a departure from many other projects in the past,” says Upadhyaya, who is executive chairperson at CEAPRED. “Traditionally our programs have been supply-driven. Development workers go provide farmers’ inputs, ask them to do what they want and that’s it.” But by working to create mutually beneficial and market-driven relationships across Nepal’s agriculture sector, Upadhyaya is confident KISAN’s impact will last long after the project is finished. “The knowledge remains locally,” he says. “Even after the project finishes out, there is some legacy in terms of capacity that remains in the field.”

A legacy, that is, that Upadhyaya probably never could have imagined when he went to take that ADC exam so many years ago. Good thing he passed.

Related Projects