Preserving Peatlands: A Hidden Key to Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions

In Indonesia, Winrock is working with a diverse coalition of partners and funders to preserve an important natural resource in the battle against climate change, prioritizing restoration while protecting livelihoods.

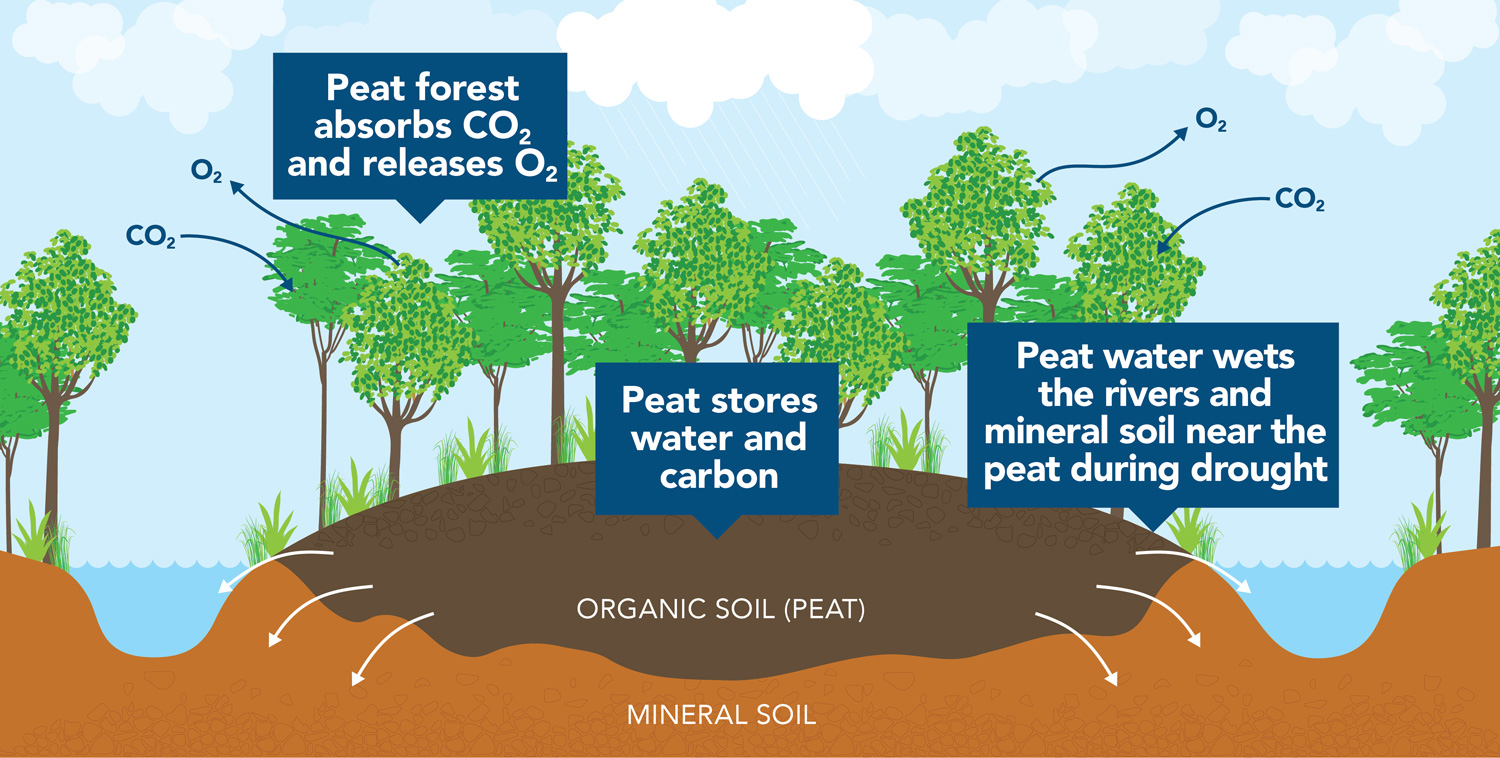

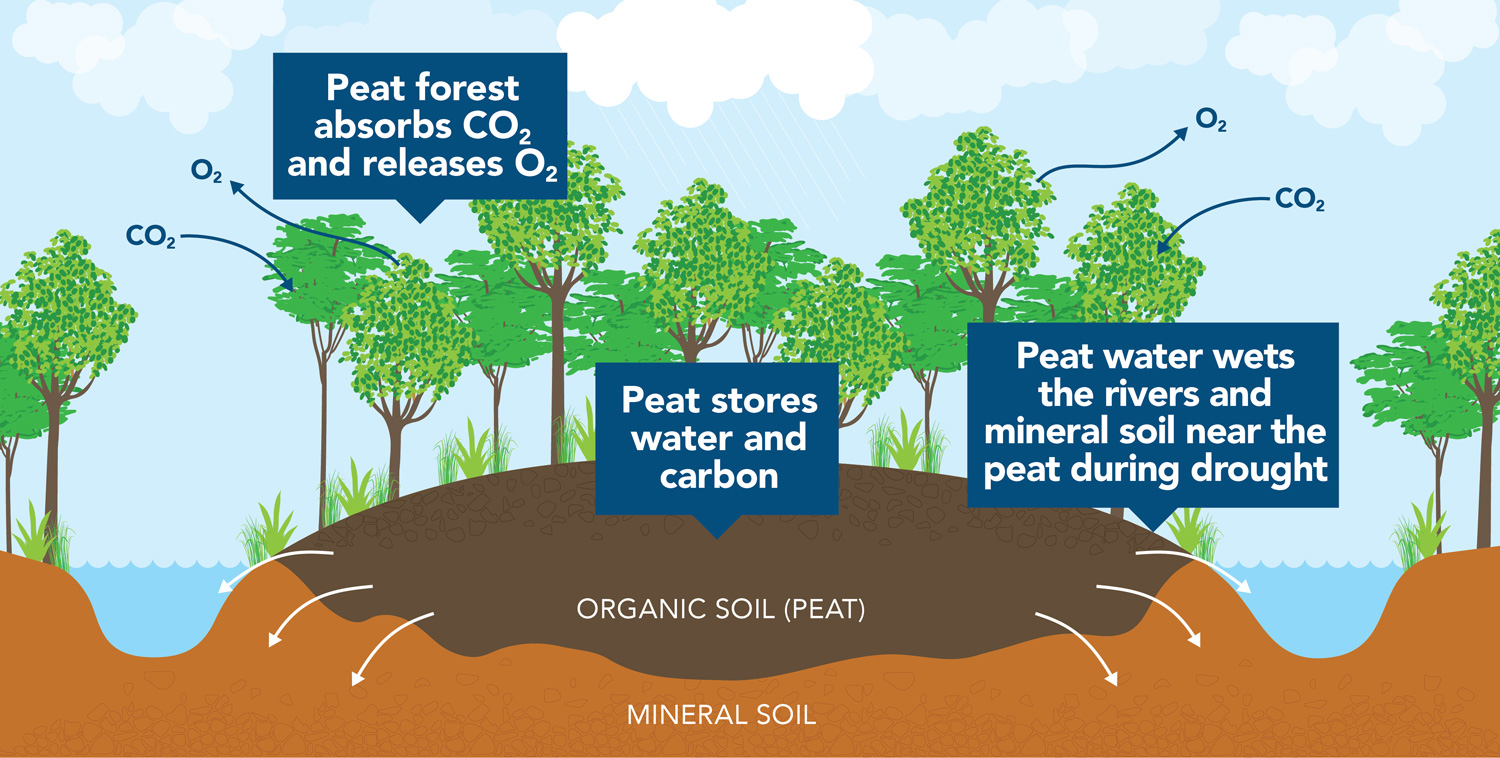

For more than a decade, Winrock International has been delving into Indonesia’s dirt ─ or more specifically, into the fascinating ancient soil type known as peat. Comprising partially decomposed organic matter, peatlands form over centuries through the arrested decay of billions of plants, the breakdown of which is delayed by the absence of oxygen in the soil’s waterlogged, acidic conditions.

Saturated with water and organic material, these spongy carbon pools began materializing about 12,000 years ago, or just after the end of the last ice age. Year-round soaking of the soil slows the decay of dead plants, stewing it into a mass of darkly colored, squishy peat that banks away the carbon those plants previously absorbed. In addition to the extensive peat deposits found across the Indonesian archipelago, which contains about one-third of the world’s total tropical peatlands, (more than any other nation on earth), peatlands are found in at least 175 other countries, with the largest in northern Europe, North America, and other countries in Southeast Asia. Vast peat tracts in the Congo Basin have recently been discovered, trapping carbon with an estimated equivalent of approximately 20 years’ worth of U.S. fossil fuel emissions.

Long cleared and drained for agriculture, and mostly undervalued except by boreal farmers who slice it into bricks for fuel, peat is an important ally in the struggle against climate change because of its incredible carbon storage capacity – if peatlands can be preserved. Globally, land development and agriculture have resulted in the ditching and draining of approximately 15% of the world’s existing peat deposits, resulting in the release of millions of tons of carbon that would otherwise remain safely sequestered. Its destruction, and the consequent release of carbon, has also greatly increased the risk of floods and fires in Indonesia over the past few decades as peatlands are converted to other economically viable uses including palm oil, acacia wood and rubber tree plantations.

As a result, Indonesia finds itself at a crossroads, balancing economic development with the environmental degradation that threatens its economy and society, and jeopardizes the country’s Paris Agreement commitment to reduce its own greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from 29-41% by 2030. Winrock has a decades-long legacy of partnership with Indonesia’s government and diverse, private sector stakeholders, environmental organizations and donors committed to helping the nation address ecological and environmental damage caused by unsustainable development. Much of Winrock’s most recent work in Indonesia has focused on peatlands protection and restoration initiatives. Three current peatlands projects, each funded by different donors, involve collaboration with communities, government and private sector partners to explore and implement innovative approaches that protect the country’s rapidly shrinking peat deposits while supporting livelihoods.

Collaborating to protect peatlands

Those projects include the Sustainable Peatland Business Model, funded by the Switzerland-based Good Energies Foundation, in which Winrock works with the government of the Siak Regency on the island of Sumatra, as well as Indonesia’s own National Peatland Restoration Agency, and private sector stakeholders to conserve peatlands through promotion of sustainable wetland cropping systems. Such systems, known collectively as paludiculture, are a scalable approach to help smallholder farmers transition to production of crops that are native to peatlands, restoring them and reducing the frequency of fires, land subsidence and emissions releases while helping producers transition to more sustainable land use systems and livelihoods.

Another Winrock project, Protecting Peatland Forest Through a Social Forestry Scheme in Siak, Indonesia, employs a community-based approach to develop a set of social forestry programs in the region, with the goal of helping community leaders, farmers and others overcome barriers to designing and implementing sustainable peatland forest management, and ultimately, to better protect ecosystems. Funded by San Francisco-based Climate and Land Use Alliance, the social forestry schemes are designed to become models for other forested peatlands in Indonesia.

A third project, implemented by Winrock and funded by the Packard Foundation, demonstrates the feasibility of improving management of peatland areas already devoted to palm oil production, with the goal of reducing emissions while increasing long-term sustainability. That project, Enhancing Capacity to Reduce GHG Emissions from Peatlands and Palm Oil Production within a Jurisdictional Framework, employs a three-pillar approach that includes development of a Green District land use planning and monitoring platform, improved smallholder management and production on peatland, and support for clean energy infrastructure development.

These and other initiatives such as Private Investment for Enhanced Resilience, an innovative climate finance project funded by the U.S. Department of State, are the latest in a portfolio of Winrock-led projects that stretch over five decades, much of it aimed at working with local partners and the government to sustain and protect Indonesia’s valuable natural resources while contributing to efforts to prevent climate change. Past collaborative projects led by Winrock in Indonesia include smart forest management, carbon monitoring, and developing best practices to reduce emissions from palm oil production.

Peatlands protection work in Indonesia has taken on increasing importance over the past decade, says Michael Netzer, technical lead for Geographic Information Systems (GIS) on Winrock’s Ecosystems Services team.

“Peatlands only cover about 3% of the global land surface,” says Netzer, who manages Winrock’s portfolio of peatlands projects in Indonesia. “About 15% of them have been developed and drained, covering just 0.4% of the land surface, however, the emissions resulting from this contribute to 10% of emissions from the land use sector and 5.6% of global anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions. This makes peatland one of the keys to reducing global emissions.”

Only about a millimeter of peat can form each year — equal to the size of a sharp pencil point — but over time, peat deposits can become many meters thick, serving as the foundation of incredibly diverse and fragile ecosystems. Indonesian peat forests support thousands of wildlife species, including birds, orangutans and leopards, and their brackish waters provide marine habitat for unique species, including the Arowana, the world’s most expensive aquarium fish, prized for its glimmering mosaic scales.

As peatlands are gradually drained, dried and converted to largescale agriculture uses, the consequences to Indonesia’s environment have become severe. Forest fires, once a rarity in Indonesia, are now an annual occurrence. In 2019, catastrophic ground fires engulfed Sumatra, releasing an estimated 708 million tons of carbon emissions and costing the country more than $5 billion, according to the World Bank. These and other huge conflagrations, as well as increased flooding caused by the elimination of natural drainage systems properly managed peatlands can provide, have taken their toll, serving as a wake-up call both to the Indonesian government and the world.

“The combination of not having enough water once drained, having a lot of fires, and having a lot of emissions is just a huge threat to the people living in Indonesia because of the fires and loss of livelihoods, but also to the rest of the world because of the climate change impact,” says Dr. Blanca Bernal, a senior specialist on Winrock’s Ecosystems Services team.

Reducing peatlands loss and fires

Winrock’s peatlands work in Indonesia includes collaboration with the Siak government and non-governmental organizations to develop the policy framework for a new approach to preserving peatlands. Part of that includes development of the Green District, which is piloting live hydrological monitoring and sustainable peatland cropping systems that allow Siak, an administrative division off the east coast of Sumatra in the Riau province, to manage peatland hydrology with a goal of reducing peatland losses and fires.

Along with Indonesia’s government, which is making strides in reviving peatlands with its National Peatland Restoration Agency, Winrock provides technical support to build out the Green District strategy to include social forestry schemes. The approach relies on involvement from local community leaders and peatlands stakeholders, including farmers, to create both economically viable and environmentally sustainable and scalable wetland paludiculture production. Paludiculture is beneficial because it produces biomass from wet and rewetted peatlands under conditions that preserve peat and facilitate carbon accumulation. Examples of food crops that fit into a paludiculture system include cultivation of sweet melon, bitter gourd, water spinach, sago palm (plant), edible fern, and pineapple, among others. The area where the social forestry schemes are implemented contains a peat dome system of more than 700,000 hectares, or roughly the size of 1.7 million football fields, combined.

The Green District approach piloted in Siak demonstrates the potential for a transformational shift in jurisdictional peatland and forest management that reduces GHG emissions and improves smallholder livelihoods while supporting sustainable land use planning. Winrock is collaborating on the initiative with the Siak Pelalawan Landscape Programme, a coalition supported by the private sector, including companies like PepsiCo and Cargill.

“Paludiculture is the growth of crops that are tolerant to wet conditions,” Bernal says. “What we’re doing in this project is fostering those as a part of rehabilitating the peatland and maintaining the productivity of the land because people produce food and income, but they can do it in a way that doesn’t mean draining the peatlands and planting palm oil. You can still grow crops that are going to be profitable and are going to support livelihoods.”

In conventional agriculture, peatlands are subject to drainage or deforestation to allow cows to graze or crops to grow. But viable wetland tolerant crops, such as sago palm — commonly used a starch source in Asia ─ could transform dried-out peatlands and help establish more sustainable, income-generating livelihoods opportunities, including aquaculture, in restored peatlands. To expand and strengthen the practice in Siak, Winrock works with local partners including the University of Riau to organize paludiculture demonstrations for the public.

Promoting sustainable land management and livelihoods

As part of the Sustainable Peatland Business Model project, Winrock and partners also developed and published a sustainable palm oil practices guide aimed at enabling palm oil producers to better manage peatlands while maintaining their livelihoods. The booklet is entitled A Protocol for Oil Palm Independent Smallholder for Sustainable and Responsible Management of Peat Areas.

And to directly address and reduce fire risks in Indonesia, Winrock works with community-based partners to restore groundwater table levels through a process known as rewetting. The most common method of rewetting is to block canals using small dams, forcing water back into peatlands to maintain its moisture. Over the summer of 2021, Winrock staff working on peatlands projects in Indonesia conducted a series of trainings for farmers and community firefighters on how to build canal blockages to slow drainage for peatland conservation and contribute to their restoration. Winrock is also developing a new forest monitoring system that will help to assess land use and baseline GHG emissions change across villages, land concessions, and other boundaries that comply with national GHG accounting criteria. The web-based system will be used to track forest losses, fires, and other land use changes to assess progress toward the country’s emissions reductions targets.

Through the Green District, Winrock is currently piloting a second tool, an innovative real-time peatland hydrological monitoring system, that uses sensors to measure water table depths. Data is migrated and displayed in a GIS mapping system that uses biophysical factors to project water table depths across the landscape, enabling identification of areas at increased risk for fires and/or increased GHG releases. Through surveillance of a specific peatland area’s fire history, its groundwater table fluctuation, and with targeted restoration goals and actions, the project helps communities accurately determine if — and how — a peatland can recover and flourish as a blooming vegetative wetland.

“One of the main barriers to implementing effective, sustainable land management in Indonesia is the lack of systems for monitoring, reporting and tracking key environmental and social variables at the jurisdictional level,” Netzer says. “Using innovative ‘smart’ technology can enable near real-time monitoring for forest changes, peatland hydrology, and fire risk. Collecting, analyzing, and sharing that information is a key element of effective policy and sustainable development planning and implementation.”

All three Winrock peatlands projects in Indonesia are nearing completion, but the work has built a foundation for ongoing peatlands preservation and restoration in collaboration with communities, government and the private sector that also protects livelihoods.

“It’s important not only in Indonesia but on the global scale,” Bernal says.

To read more about peatlands and access presentations from the virtual peatlands pavilion at the U.N.’s 2021 Annual Conference of Parties in Glasgow, (COP26) click on the Global Peatlands Initiative website.

Related Projects

Protecting Peatland Forest Through a Social Forestry Scheme in Siak, Indonesia

The draining of carbon-rich peatlands in Indonesia for agriculture has led in recent decades to increasingly large fires and greenhouse gas emissions. Winrock is working with local communities to develop a set of peatland Social Forestry schemes in Indonesia’s Siak District to overcome the barriers to sustainable peatland forest management and promote the protection of […]

Sustainable Peatland Business Model

The degradation of carbon-rich peatlands in Indonesia has led to destructive wildfires and surging greenhouse gas emissions in recent years. Winrock is working with multiple groups in Indonesia to identify opportunities for peatland restoration, including the government of the Siak regency, Indonesia’s National Peatland Restoration Agency, the private sector and local stakeholders. These efforts target […]

Private Investment for Enhanced Resilience (PIER)

PIER is an innovative climate finance project that incentivizes private sector investments in support of national development objectives that address climate change, such as National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), within countries of strategic interest to the United States, including Bangladesh, Dominican Republic, Ghana, Grenada, Guyana, Indonesia, Jamaica, Mozambique, Peru, Saint Lucia, Tanzania, and Vietnam. PIER demonstrates […]

The Alliance for Sustainable Palm Oil or Aliansi Sawit Lestari Indonesia (ASLI)

In the last 15 years, Indonesia’s palm oil sector has seen an enormous production increase, leading to growth in smallholder incomes and the overall national economy. However, this expansion has threatened the environment by driving high deforestation and peatland degradation rates. This project, a partnership between USAID, Winrock and Perkumpulan Sawit Lestari, aims to strengthen […]

LESTARI

Indonesia boasts the third-largest expanse of tropical forests in the world. Sustainably managing this unique economic and ecological resource is important to both the economic well-being of many Indonesians and a world community increasingly focused on climate change. As a partnering organization in this USAID-funded project implemented by Tetra Tech, Winrock’s role is to provide […]

Indonesia Carbon Monitoring System

A lot of field work is necessary to truly understand the role of forests in climate change — both the benefits of preserving them and the impact of cutting them down. As part of a NASA-funded initiative, Winrock is spearheading the planning, collection and analysis of data to understand the impacts of selective logging on…

Smallholder Protocol for Peat

Smallholders produce around 40 percent of Indonesia’s palm oil, an amount that is expected to increase due to the lack of land suitable for new large-scale plantations. However, a lack of resources and technical capacity often leads to extremely low productivity and unsustainable management at small plantations. With funding from IDH, Cargill and Costco, this…