The Winrock Q&A: Accelerating healthcare solutions and building partnerships in the Heartland

Jordyn Schneider, a program officer with the Human & Community Development team in Winrock’s U.S. Programs group, brings nearly a decade of experience in public health and community development to help communities thrive. Schneider helps lead the team’s program design and evaluation efforts, merging innovative and evidence-based practices in a community-driven approach to development. She holds a master’s degree in public health, with a focus on rural and global health, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. We asked for some of her top takeaways from managing Winrock’s successful SHARE I&II projects – both funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

SHARE − short for Supporting Health Advances for Rural Employees – built health-focused workplace cultures across six rural counties in Arkansas. The project increased access to healthcare services for rural workers; it also positively shifted organizational capacity to support employees’ health. Rural employers demonstrated increased awareness, understanding, responsibility, and concern for the health and well-being of their employees and for having a healthy workforce, with more than 2,800 employees reached across 11 different industries over the project’s duration.

Studies show that in many rural areas of the U.S., access to healthcare is limited, while rates of chronic disease are often higher than in urban areas. For rural employers, this means employees are more likely to have health concerns and less likely to have the resources to address them. What have we learned from Winrock’s work on rural health care access?

Jordyn: We all know what we should do to be healthier: Eat more fruits and vegetables, get regular wellness check-ups, exercise more frequently, follow the doctor’s instructions for managing health conditions. But while knowledge is necessary, it’s usually not sufficient for supporting healthy behaviors. We all need a variety of reinforcements to help make the healthy choice the easy choice. We’re much more likely to eat, say, broccoli, if we live near a grocery store that regularly sells broccoli and the broccoli at the store is good quality and affordable. People in urban areas have more access to good quality, affordable broccoli than people in rural areas because there is a higher concentration of grocery stores, which means better produce distribution and lower prices, and more options for getting to the store, like public transportation and safe walking or biking options. This is also true for places to exercise, primary care clinics and hospitals, and many other social factors that influence health.

People who live in rural areas in the U.S. generally experience higher rates of chronic illnesses (like diabetes, heart disease, and obesity), mental health challenges, and overall poorer health outcomes compared to their urban counterparts because of the disproportionately lower access to healthcare, social, and community supports. These are the “deserts” we hear about so often — food deserts, mental health resource deserts, maternal healthcare deserts − resources just aren’t as available, the further away from urban centers you go. Living in a healthcare desert makes it easier to develop a “lifestyle” disease, less likely for it to be diagnosed, and more difficult for it be to properly managed. [Note: lifestyle disease is any medical disorder or condition thought to be produced or made worse by aspects of a person’s lifestyle, such as diet and/or level of physical activity.]

Should employers in rural areas be more proactive about ensuring their employees have better access to basic healthcare assessments, services and information?

Jordyn: The average employee spends 30% of their waking hours at work. This makes work and the workplace significant influencers on health. In the U.S., we’ve become accustomed to the idea that employers are responsible for the physical safety (health) of their employees, and a significant benefit for many employed people is employer-based health insurance. During COVID, employers were in the spotlight — or under the microscope — for how they were prioritizing their employees’ health needs. On-site testing and vaccination, sanitizing and masking measures, allowing remote and hybrid work, increased leave for sickness and caretaking, and sharing health information were all effective strategies that employers used to prevent the spread of covid and keep operations afloat. Importantly, employers weren’t on their own to do this; healthcare providers, public health institutions and all levels of government used their expertise and resources to help keep employees healthy and businesses open. In areas with access to more resources, businesses were much better able to implement these strategies and partner effectively with health organizations.

All 30 employers who participated in SHARE stated that employee health is a major concern. Workforce is limited in rural areas and employee turnover, absenteeism and health insurance rates are costly. In fact, one company shared that several years ago they nearly closed, which would have resulted in the loss of over 200 jobs, a catastrophic economic impact for the surrounding region. One of the strategies that allowed them to maintain operations was decreasing healthcare costs through expanding employee wellness programming.

Beyond business operations, SHARE employers genuinely care about their employees’ health and well-being. Sandy Daniels, a manager at Hayes Mechanical, explained why the company wanted to participate in SHARE:

“Our crews’ health is important. They’re out all over the country installing grain bins in remote places. We actually lost someone to a heart attack a few years ago. The crew was two hours away from an ambulance and didn’t have an AED [Automated External Defibrillator − a portable, electronic device used to restore a normal heart rhythm in someone experiencing a sudden cardiac arrest.] He had a wife and young kids. We think he had high blood pressure and didn’t know it.”

The ripple effects of this perhaps preventable death were felt throughout that company and small community. The question that SHARE employers were asking was not if they should do more to promote employee wellness, but how. Programs like SHARE provide a template for the how.

In 2017, only 46% of worksites offered health promotion programs. Of these, 75% indicated that technical assistance related to best practices in promoting employee health would be useful and only 28% had partnerships with organizations to help with employee wellness, according to CDC data. SHARE was designed to provide this technical assistance and facilitate these partnerships.

How does improved rural health access contribute to community resilience and rural economic development?

Jordyn: In the past 30 years, Winrock’s Human & Community Development team has led over two dozen initiatives funded by USDA Rural Development providing over $7 million in services to rural U.S. communities. SHARE is just one of these initiatives, and has been funded by the Delta Healthcare Services Program. This program was created to address the continued unmet health needs in the Delta Region of the U.S., one of the most health disparate regions in the country. Getting this work done requires a consortium of health care professionals, institutions of higher education and research, and economic development entities to coordinate efforts to improve and increase access to health services in these medically underserved areas.

It’s no secret that the average age of farmers is increasing, and that farming poses many health risks such as manual labor leading to injury and chronic pain, financial stress, and chemical and sun exposure. Many farmers are self-employed, which makes affording health insurance challenging. With seasonal, weather-dependent work, losing one day to travel to a doctor’s appointment in the nearest town two hours away could mean the loss of thousands of dollars. Improving health services in rural areas directly impacts and supports the farm workforce by bringing services closer to home and supporting innovative models of care. Healthier farm workforces, and healthier rural communities contribute to healthier Heartland economies.

A number of people who took advantage of basic equipment that was made available at workplaces through SHARE, like blood pressure monitors, were startled by their results and immediately sought medical care. What does that tell us?

Jordyn: First, there are a lot of people living with hypertension that don’t know it or have been diagnosed but don’t have their blood pressure controlled. Since 2020, SHARE has provided free health screenings to over 1,100 employees as part of worksite wellness events. Of these, 64% had elevated blood pressure compared to the state rate of 41% for hypertension. At events, health staff urged several employees to leave work and seek emergency medical care due to stroke level blood pressure. During one event at a community college, for example, a staff member said he wasn’t planning to get screened because he was already taking blood pressure medication. A colleague encouraged him to go anyway, and he discovered that his blood pressure was at stroke level. He then went to an emergency room and spent time in the hospital getting his blood pressure controlled. His colleague later told us: “He could have died if we hadn’t had that event.”

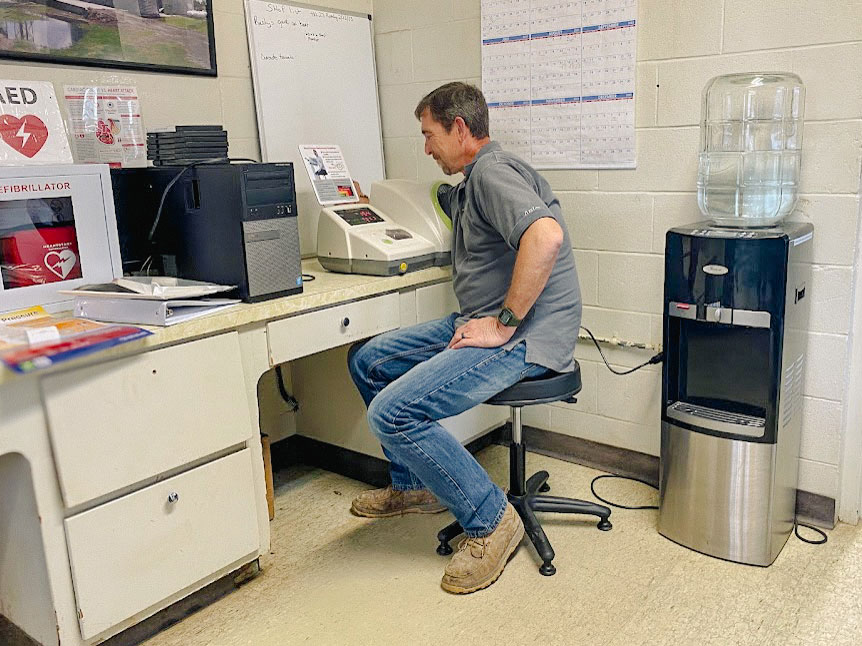

Knowing that high blood pressure was a concern for most of their employees, we worked with employers to change policies, systems and the workplace environment to support prevention and better management of hypertension and other chronic diseases. We used grant funds to place blood pressure kiosks in breakrooms. In some areas, this was the only blood pressure kiosk in the county — none had Walgreens, Walmart, CVS, etc. Several employers called within a month to say that they had already used all of the receipt paper that printed blood pressure results at the kiosk, and several employees had asked to leave work to go to the doctor after having very high blood pressure readings.

One city’s human resources director shared her personal story with us: “I had a stroke while I was at work a few years ago. Another co-worker and I often ask one of the firefighters to check our blood pressure. It’s something I’m conscious of now and hope others will be too with this blood pressure monitor.”

After we completed a workplace health assessment, another employer instated a policy preventing energy drinks from being sold in their vending area. In a letter to the vending company that she shared with us, she wrote: “Our company has been promoting a healthier workforce and working on educating our employees to make better food and drink choices. We know that we can’t stop or change the mindset of everyone, but we at least want to stop offering things that we know are bad for our health.”

These changes — hosting annual worksite wellness events, placing blood pressure kiosks in break rooms, making vending options healthier — go a long way in fostering a culture of health in the workplace. SHARE builds the capacity of rural employers to make these changes by helping them identify employee health concerns and no or low-cost ways to address them.

Can you talk about the power of partnerships at the heart of SHARE’s design? How do SHARE partners complement each other?

Jordyn: Partnership is important in any social endeavor. When working to increase access to health services, it’s critical. Multi-sector partnerships were a key factor in businesses being able to protect employee health during COVID-19. As we’re settling into a post-COVID “new normal,” there’s an opportunity to continue and reinforce these partnerships with an emphasis on general health and wellbeing rather than crisis response.

Winrock has led consortiums of technical experts and local healthcare providers through different iterations of SHARE. Federally Qualified Health Centers are the primary, sometimes only, healthcare providers in the rural counties that SHARE has served. Winrock partners with FQHCs to provide onsite health screenings, health education, and referral services to employees at worksite wellness events. Both clinical and outreach staff, such as community health workers or patient navigators, attend these events and are well-positioned to answer medical questions that arise, schedule follow-up doctor visits, or refer to community services.

As one staff member from the East Arkansas Family Health Center shared: “One gentleman commutes from Memphis to Blytheville for work. His blood pressure was high, and he was showing signs of mental distress. We worked to get him an appointment that weekend so he wouldn’t have to miss work.” Another from Mainline Health Systems said: “Of the 12 employees that we screened, all had high readings for either blood pressure, cholesterol, or glucose. None had a PCP [primary care physician.]” Several SHARE employers have maintained their relationships with FQHCs to continue worksite wellness events on an annual basis, many sharing that these events are potentially lifesaving for some of their employees.

In addition to providing medical and social services for employees, SHARE increased organizational capacity for making systems-level changes that impact health. For example, Winrock partners with International Medical Corps to leverage their expertise in disaster preparedness and response. IMC trains rural employers in hazard vulnerability assessment and essentials of business continuity to equip businesses with knowledge and strategies of how to prepare for and respond to crises that threaten operations, such as natural disasters, public health emergencies and supply chain disruptions.

In terms of sustainability, the American Heart Association added tremendous value to SHARE by providing deeper support to employers specifically wanting to address heart-related health concerns. They’ve worked with employers to develop cardiac emergency response plans, connect with local CPR training programs, and have provided a variety of educational resources to accompany the blood pressure monitors and AEDs purchased with grant funds for worksites. Ongoing partnership through the AHA’s Well Being Works Better Program, which is similar to SHARE, allows employers to remain intensely engaged in worksite wellness initiatives past their participation in SHARE.

[Additional SHARE partners include Lee County Cooperative Clinic; Mid-Delta Health Systems; and RISE International Consulting.]

How is Winrock sharing knowledge about improved access to rural healthcare in other locations?

Jordyn: Winrock is dedicated to expanding the SHARE model and continually seeks partnerships with funders, employers, and employees to enhance community health access. By fostering collaborative efforts, we aim to replicate and adapt this innovative approach across various regions of Arkansas and beyond.

The sustainability built into SHARE allows for not just initial investments but a pathway for ongoing engagement. Through comprehensive training and support, employers can maintain and grow these health initiatives independently. Our established partnerships with local Federally Qualified Health Centers, networks like the Community Health Centers of Arkansas, and national health organizations such as the American Heart Association, all facilitate sharing of best practices, fostering a collaborative environment where stakeholders can learn from each other.

Moreover, SHARE’s flexible, scalable model means it’s not limited to specific areas – it can thrive through hyper-local initiatives or larger state-led projects, adapting to the unique needs of communities. As we learn from implementations across the country, Winrock is enthusiastic about collaborating with like-minded organizations that share our passion for enhancing community health. We encourage potential partners to connect with us, as together we can achieve significant improvements in access to vital healthcare information and assessments.

Final thoughts?

Jordyn: Winrock’s work with public and private sector partners to improve rural healthcare is going strong. U.S. Programs’ new MaternaTech project, for example, is addressing Arkansas’s maternal health crisis by connecting Series A-backed startup enterprises with top local providers. It’s funded by the Arkansas Economic Development Commission and the Walton Family Foundation, and key partners are Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield, Baptist Health, and Washington Regional Medical Center. It’s helping to develop virtual maternity care platforms, tech-enabled midwife/OB clinics, and community-focused maternal support.

That’s just one example; others include our work with rural communities on the opioid epidemic in partnership with the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Ozarka College and Arisa Health. Winrock’s edge is in creating partnerships where better healthcare access and technological and entrepreneurial innovation converge, helping to build rural resilience.

Related Projects

Supporting Health Advances for Rural Employees (SHARE I and SHARE II)

Productivity is highest when employees are healthy. Increased sick time, disability, and employee turnover are all costly to employers. In rural areas, access to healthcare is limited, while rates of chronic disease are often much higher than in urban areas. For rural employers, this means that employees are more likely to have health concerns and […]

Delta Understanding and Preventing Substance and Opioid Use Disorder in Rurality (Delta UPSOAR)

The opioid crisis in the United States threatens health and prosperity in communities of all sizes and families of all socio-economic backgrounds. Like much of rural America, north-central and northeast Arkansas suffers high rates of opioid misuse and limited access to preventative education and recovery resources. Delta UPSOAR is an innovative and local response specifically designed to […]