Working with U.S. Farmers and Local Partners to Protect Water and Soil Health

Winrock’s Wallace Center and Ecosystem Services teams are partnering with farmers and allies to explore new strategies to protect the environment without endangering their bottom lines.

Wisconsin’s Kickapoo River has a complicated history.

For thousands of years, Indigenous people managed this agroecological landscape for foraged food, crops, and game ── most recently the Ho-Chunk, Oceti Sakowin, Meskwaki, and Kickapoo people. When European settlers displaced these Indigenous peoples from much of their homeland, cut down trees, and began to plow the watershed’s steep topography, the river’s periodic flooding became more frequent. The Kickapoo River, the longest tributary of the Wisconsin River, now floods about every other year with increasing severity.

Decades of dam and levee building efforts haven’t held up under the extreme weather events of our changing climate, resulting in catastrophic losses in the communities of the Kickapoo Watershed. Unsustainable agriculture practices in and around the watershed also take an environmental toll, especially on water quality.

High-disturbance tillage, inefficient fertilizer application and other practices, such as leaving farm fields inactive and uncovered during winter months (fallowing), contribute to nutrient overloads downstream that drive warm-weather algae blooms in the Gulf of Mexico, known as “dead zones.” The algae ceiling in the Gulf depletes the oxygen in the surrounding waters, creating a nearly impossible environment for marine life. The condition, called hypoxia, yielded a 6,334-square-mile dead zone, an area larger than Connecticut, in the Gulf in the 2021 summer, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. More agricultural runoff, driven by intensifying weather events, is making the problem worse.

Working in the headwaters of these water quality and quantity issues, Winrock’s Wallace Center and Ecosystem Services teams are partnering with concerned farmers and partners in the Kickapoo River area, drawing from this local expertise on agriculture and water quality in the watershed. Collaboratively, they are piloting a range of climate-resilient, sustainable farming practices ── primarily tied to increased regenerative grazing ── that can help farmers and conservationists meet their economic and environmental goals, together. The vision: a watershed with profitable family farms that help to hold water and nutrients in their soils, and spur further local and downstream efforts to improve water quality.

Soil health is vital to managing both water quality and quantity, according to Pete Huff, co-director of the Wallace Center, and Elisabeth Spratt, project manager for the Pasture Project’s Farmer-Driven Water Quality Project (FDWQ) in the Kickapoo River Watershed. The 3.5-year FDWQ project, funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), began in 2019 and includes water quality monitoring and expanding conservation-focused best management practices in Tainter Creek Watershed, part of the Kickapoo Watershed and Mississippi River Basin, to achieve reductions in phosphorus and soil loss. Too much phosphorus and sediment in the water contribute to increased algae, which results in decreased amounts of dissolved oxygen in the water.

The effort is part of the Wallace Center’s Pasture Project, which works to improve water quality through agriculture by addressing barriers to expanding regenerative grazing and other regenerative agriculture practices in the U.S. Upper Midwest. Among other benefits, regenerative grazing helps create resilience to climate change by rehabilitating soil and supporting improved biodiversity above and below ground. Scientists are increasingly demonstrating that undisturbed, continuously covered soils such as grasslands sequester more carbon, particularly in the presence of grazing animals. Practices like “no-till” farming, cover cropping, perennial crops, and regenerative grazing are efforts to build healthy soils on agricultural and working lands.

Healthy soil with lots of living microorganisms and roots from above-ground plant ecosystems creates more of a sponge-like surface that allows water to slow down, sink in and remain in the soil. Regenerative grazing improves soil health by keeping the soil covered with forages year-round and minimizing soil disturbance by eliminating the need for tillage.

“The less of that living sponge and continuous plant cover that we have, the less ability we have to deal with or bounce back from extreme weather events” and associated flooding and drought, Huff said. Unhealthy, uncovered soil struggles to capture water, allowing it to quickly runoff into local streams and creeks, carrying nutrients like phosphorus with it. Regenerative grazing can simultaneously improve water quality and help to address water quantity issues (mitigating potential flooding) because healthier soils hold and sink more water, Spratt notes.

Winrock’s FDWQ project focuses on three key techniques to avoid runoff into the Kickapoo River Watershed. It offers technical assistance and cost-share to farmers through training events, webinars, and one-on-one support; develops and pilots a decision-making support tool through an online application; and provides ongoing water quality assessment of phosphorus and turbidity, in collaboration with participating Midwestern farmers, technical assistance providers, and academics.

“Our partners measure water quality because it helps us understand how we’re doing on soil health and the agricultural production being in the right relation to the ecosystem that it’s in,” Spratt said.

Farmers who engage with the program work through progressive technical assistance, with the goal of adding more regenerative grazing practices to their farm systems. With Wallace Center’s support, farmers first map out their own farm infrastructure, identify soil types, and discuss resource concerns and goals with technical service providers. Eventually, they develop grazing plans with experts and apply for cost-sharing offered by FDWQ. It’s a gradual process that leans on each farmer’s preferences and expertise. So far, 21 farmers have completed mapping and 15 have completed whole farm assessments, while 10 have established grazing plans and nine are at the final stage of applying for or receiving cost-sharing assistance.

“One of the things that makes this project work is the leadership of farmers who want to protect streams and ecosystems for future generations,” Spratt said. “We work closely with the Tainter Creek Farmer-Led Watershed Council, a group of farmers focused on the health of the watershed they live in. We just provide resources and technical assistance to help make their goals a reality and learn from them about ingredients for success.”

Though only in its second year, the project has made significant progress in helping farmers analyze and shift their own practices, supporting them to meet their goals of environmental stewardship. The project is made possible with the expertise of its partners, including the Tainter Creek Farmer-Led Watershed Council, the Valley Stewardship Network, which supports farmers directly, and the University of Wisconsin Madison, which helps develop the decision-making support tool.

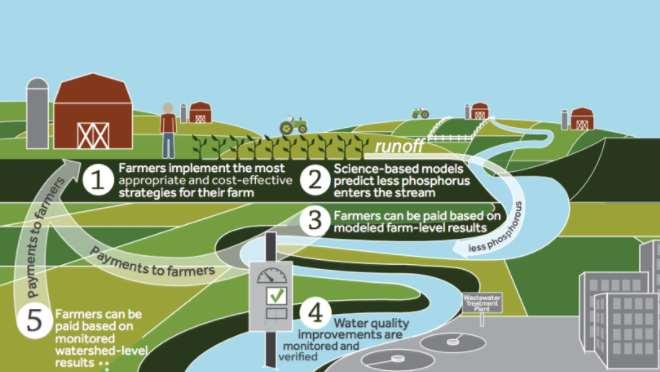

The Pasture Project’s focus on scalable, market-driven solutions for building healthy soils, viable farms, and resilient communities aligns with other Winrock-led conservation initiatives that also help to protect watersheds in the U.S. Over the past decade, Winrock has helped to pilot an innovative “Pay-for-Performance” (PFP) conservation approach that supports farmers to become more climate-resilient and meet improved water quality standards, in part by adopting ecologically friendly agriculture practices that help to reduce agricultural runoff.

Winrock-implemented PFP conservation projects aim to reduce the kinds of conditions ── such as nutrient loss from land to water ── that impair water quality and contribute to eutrophication, or overabundance of nutrients, in water. The PFP conservation approach benefits farmers by paying for nutrient loss reductions, incentivizing them to adopt more cost-effective practices for each field. Such cost-effectiveness depends on many factors, such as a field’s slope, soils, and crops. Good performance results in water quality improvements through reduced nutrient losses into rivers and streams, and less eutrophication in receiving water bodies, downstream.

“Water quality impacts and climate change impacts are undoubtedly the two most important environmental issues related to agriculture,” said Dr. Jon Winsten, an agricultural economist with Winrock’s Ecosystem Services team. Winsten led a Winrock PFP conservation project that concluded recently in Ohio’s Old Woman Creek Watershed, which drains directly into Lake Erie.

Winrock helped to pioneer PFP conservation by using computer simulation models to estimate the performance of a specific practice applied in a specific field. The work involves collaboration between conservation technicians ── either from the government or the private sector ── and participating farmers to quantify baseline losses and then run scenarios to assess reductions and costs. The full economic costs of each scenario and of nutrient loss reduction are calculated and with them, farmers make informed decisions about which practices to implement in their specific fields. Any practice for which the payment rate is greater than the cost per pound will increase farm profits.

In the PFP pilot in Ohio’s Old Woman Creek Watershed, the project offered farmers $35 per pound of phosphorus loss reduction and $5 per pound of nitrogen. The program resulted in a reduction of 337 pounds of phosphorus and 7,133 pounds of nitrogen loss over 1,259 acres while increasing farm profits by almost $20,000, demonstrating that the more cost-effective the nutrient reductions, the more profits can be retained by farmers. Winrock conducted the project in partnership with the Erie County Soil and Water Conservation District and Heidelberg University, with funding from EPA’s Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.

The Old Woman Creek Watershed pilot followed the Winrock-implemented Milwaukee River Pay-For-Performance Project, which successfully reduced phosphorus losses by 40 percent. Conducted in partnership with the Sand County Foundation and the Delta Institute, and funded by the Great Lakes Protection Fund, the success of that project prompted Winrock to develop and publish a guide to share learning about the PFP approach. The guidebook, Pay-For-Performance Conservation: A How-To Guide, provides comprehensive guidance for applying and managing PFP conservation programs that can be used by administrators of water treatment plants, conservation groups, and others concerned with managing agricultural water quality issues.

The PFP approach makes conservation a business decision ── and that resonates with farmers, Winsten said. “Pay-for-Performance can be done in an efficient way so that the benefits, in terms of improved cost-effectiveness of agricultural pollution control, are greater than the additional costs of the time and effort by the technicians and by the farmers.”

In tandem with initiatives like the Wallace Center’s Pasture Project, Winrock is introducing and promoting new approaches and tools that support farmers and other stakeholders to better manage and protect the health of two of the world’s most vital natural resources: soil and water, both of which are crucial in the fight against climate change.

Related Projects

Farmer Driven Water Quality in Mississippi River Basin

Agricultural production using high-disturbance tillage, inefficient fertilizer application, and winter fallowing is a leading cause of the nutrient and sediment inputs driving hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico. The Wallace Center’s Farmer-Driven Water Quality project will conduct water quality monitoring and increase the use of conservation grazing best management practices in Wisconsin’s Kickapoo River Watershed…