Investing in Earth with organic agriculture, locally

Meredith Martin-Moats, a local food advocate and farmer from Yell County, Arkansas, who raises mealworms and flowers, hopped in her car in Harkey Valley and drove 20 minutes south to the Yell County Extension Office for a workshop on organic agriculture and markets. She’d heard about the Winrock International event on Facebook and hoped to learn about access to markets for organic agriculture to support her community of small farmers, including other growers and people raising food for themselves and neighbors.

“We’re trying to look at how we can identify some of the barriers to local food production and selling in the county and create some best practices around it,” says Martin-Moats, who volunteers at a local, community-based nonprofit called McElroy House. “I grow and sell at the farmer’s market. I love the farmer’s market. But it’s not an economical, viable option to create income,” she says – at least, not enough income for most farmers in rural communities.

Martin-Moats is interested in helping other farmers, including lower-income producers, women and newcomers who’ve migrated from other areas and countries, including Mexico and Central America. She has found that many smaller growers, including migrants, have deep knowledge and experience growing food ─ especially vegetables ─ that prosper in Arkansas’s climate. McElroy House won an Access to Local Food grant last year from the Arkansas Community Foundation to help build a network of multilingual people in Yell County who are interested in learning about companion planting, connecting to land ownership opportunities, finding new markets and producing more local food. (Winrock also received an Access to Local Food grant last year.)

Advancing Organic Agriculture in the Mid-South

That’s why Martin-Moats wanted to learn about a Winrock-led project to provide locally relevant, research-based evidence of organic farming’s economic viability in her region. In addition to generating higher value produce, organic farming is gentler on the environment. It has a smaller carbon footprint than conventional agriculture, partly because it prohibits the use of fossil-fuel based fertilizers and pesticides.

“If we compare conventional agriculture with organic agriculture, we could think of conventional agriculture practices as reacting to pests, diseases and insects that may diminish a crop, while organic agriculture tries to work in harmony with Earth’s natural cycles and ecological systems to address these production issues,” said Joseph Schafer, a Winrock program manager who is overseeing the Advancing Organic Agriculture in the Mid-South project.

The project ─ which just finished its first year-long demonstration cycle with a series of organic crops ─ is funded by the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Its goal is to help farmers interested in exploring organic agriculture in the Mid-South region overcome some of the biggest barriers to a potential transition. Those challenges include a steep learning curve for the more complex processes and systems required for organic crop management and pest control and lack of information about and understanding of the organic certification process.

The Mid-South region has unique farming conditions including longer growing seasons, generally more rain and wetter soils, and warmer temperatures than other parts of the country. When farmers in the region explain their hesitations to explore organic production, they often cite concerns about their ability to control weeds and pests in an organic setup. They also say they need more locally sourced and evidence-based information about how to farm organically in the unique environment and climate of the Mid-South. The USDA project, implemented by Winrock with partners, is designed to help interested producers learn more.

The AOAMS project is part of the USDA’s Organic Research and Extension Initiative. It’s being conducted in collaboration with the USDA Agriculture Research Service, Tennessee-based Agricenter International, the Natural Soybean and Grain Alliance, the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture and the University of Missouri at the Southwest Research, Extension and Education Center. Through controlled scientific trials on specific row crops and management, the four-year project is examining farming practices that can effectively manage local organic production challenges and demonstrate successful organic systems on farm-scale plots in Arkansas, Missouri and Tennessee. In the process, the project provides learning opportunities to curious community members and small-scale growers like Martin-Moats, as well as to commercial farmers who are exploring a transition to organic farming and/or pursuing USDA Organic certification. The goal is to collect and share data on how specific farming practices – tested at small research trial plots and demonstrated at the larger, farm-scale plots ─ impact crop production, insect management, soil health and economic viability. Results and other information from the project are being shared through outreach and education – such as the inaugural project workshop in Danville ─ to the public and farmers to help accelerate interest in and adoption of organic production in the region.

Growing demand for climate-friendly food

Organic production is the fastest-growing sector of U.S. agriculture, with farms and ranches selling $11.2 billion in certified organic commodities in 2021, a whopping 13% increase over sales in 2019, according to USDA data. Of that total, about 54% of certified organic sales were for crops, and about 46% was for livestock, poultry and related products. The rising demand is driven by increasingly environmentally aware and climate-smart consumers. Organic farming helps reduce harmful chemicals and fossil fuel-based herbicides and pesticides used routinely in conventional agriculture. The use of conventional agri-inputs not only releases greenhouse gases, it also endangers groundwater – which an estimated 50% of the U.S. population relies upon for drinking water, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Organic farming also builds healthier soils, keeps water sources safer and encourages biodiversity through practices including reduced tillage or no-till land preparation.

No-till farming also helps mitigate climate change by minimizing soil disturbance, increasing soil’s capacity to retain carbon and moisture. No-till farming helps cut GHG releases because it minimizes the need for fossil-fuel powered farm machinery. The USDA estimates that across the U.S., farmers who use no-till farming save 588 million gallons of diesel fuel annually, or enough energy to power over 720,000 homes for a year; it also prevents around 5.8 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions, or the equivalent of taking more than 1 million cars off the road, according to an article by the Environmental and Energy Study Institute. In the AOAMS project, no-till organic practices are being studied to determine their effectiveness in the region. If successful, the practice could provide additional environmental and economic benefits to farmers.

So why haven’t farmers in Mid-South states like Arkansas, Tennessee and Missouri jumped on opportunities to reach new markets and become better environmental stewards through organic production?

The answer lies in both geography and climate. Farmers in the Mid-South must cope with hot and humid summers and generally milder winters, which makes it harder to overcome weeds, pests, and plant diseases efficiently without conventional inputs. And the region’s infamously compacted, clay-like soil makes it more difficult to grow crops without conventional tillage compared to regions where organic farming has taken off faster. Though data examining organic farming by region in the U.S. is scanty, the USDA’s Organic Integrity Database indicates that Mid-South states lag far behind other regions where conditions are more conducive. Data for Arkansas, Missouri and Tennessee showed 811 certified organic farms or businesses in the three states. By comparison, the nation’s three top organic producers – Wisconsin, California and New York – had a combined 8,516 certified organic farms or businesses.

Leveling the field for organics

The USDA Mid-South project aims to help farmers in the region transition to organic farming by conducting on-farm organic demonstrations and providing support through the process of obtaining USDA Organic certification. The project shares information on resources and programs including the USDA’s Organic Certification Cost Share Program, which reimburses interested farmers up to 50% of certification costs. Obtaining official USDA certification is crucial for producers who want to farm organically because it enables them to differentiate their products and pursue new, higher-value markets. Certification also provides consumers and retailers with the guarantee that the produce they’re buying and selling is produced without chemicals.

A year into the project and just a few weeks before Earth Day, AOMS held its first workshop in Danville. The session included overviews by Winrock’s Schafer, as well as Kelly Cartwright, the director of the National Soybean and Grain Alliance, who later presented information on organic markets.

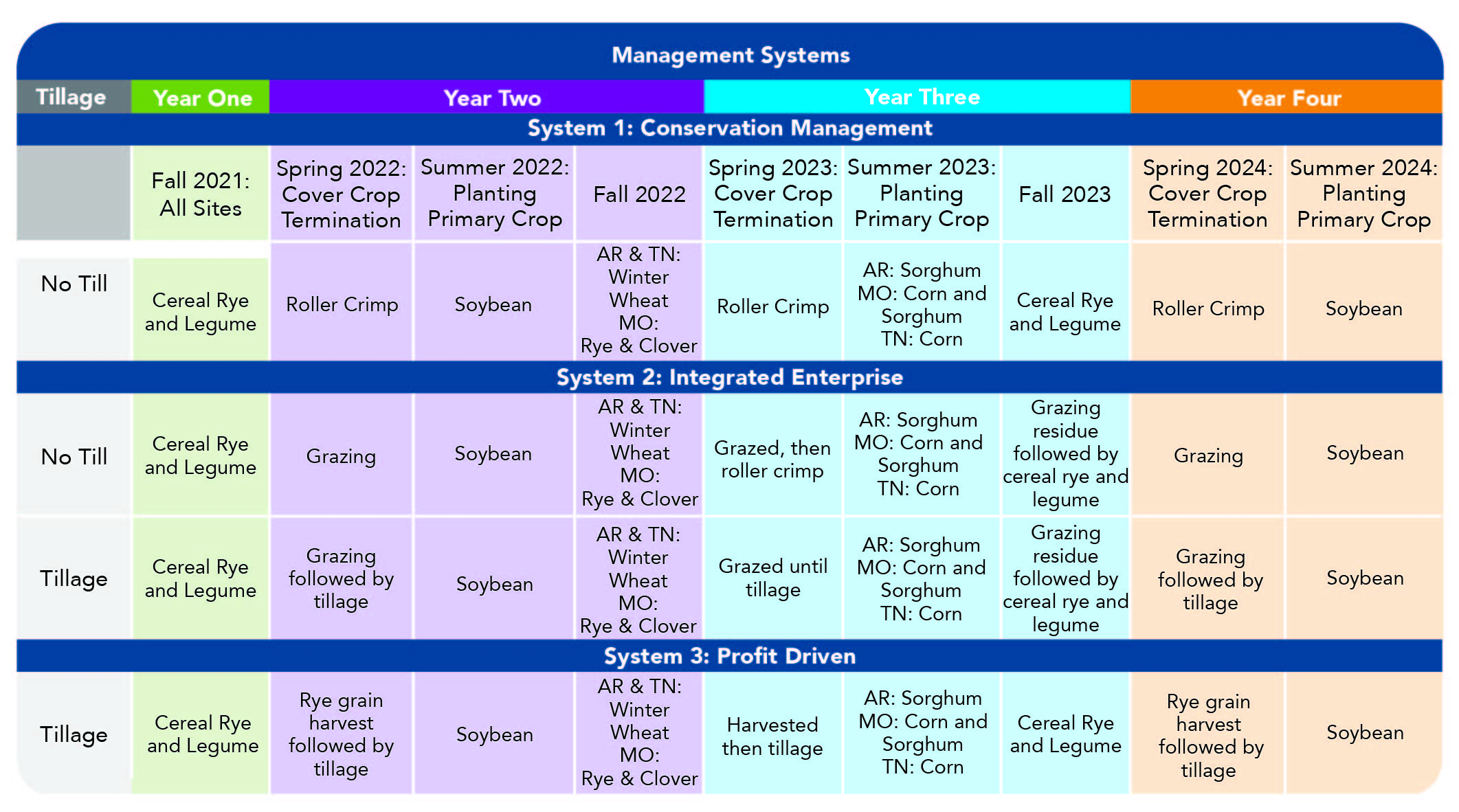

Christine Nieman, research animal specialist for the USDA Agricultural Research Service at the Dale Bumpers Small Farms Research Center, covered the three different research treatments and organic practices used at different demonstration farm sites in the three states. Those included various combinations of no-till with cover crops, cattle grazing and conventional tillage. Organic row crops grown at the sites included cereal rye, soybean, sorghum, and corn, while varying cover crops (see graphic, below) planted between seasons – and plowed under, later, to serve as green manures ─ helped build soil health and maintain soil moisture while controlling pests, weeds and diseases. Cover crops used at the demonstration sites, which ranged in size from 12-20 acres, included winter wheat, rye and clover, the latter of which can fix nitrogen in the soil and attract pollinators.

“It’s not just about productivity, but also about controlling erosion and keeping a biological life cycle within our soil so it’s not just a dead entity. We’re trying to manage our soils to keep them healthier,” USDA’s Nieman said.

Mike Popp, a professor of agricultural economics and agribusiness at the University of Arkansas, presented information on the economic viability of organic agriculture in Arkansas with a body of evidence that is continuing to grow as the project unfolds.

The AOAMS team already has learned important lessons to use over the next three years of the project, Schafer said. They’ve learned that planting crops as early as possible is important to provide the best chance for the crop to compete with weeds and pests, and ultimately achieve the best yields possible in that system. They’ve discovered that the breakeven yield for organic production is lower in organic systems than in conventional production because farmers spend less money on inputs and equipment to manage their fields. Additionally, Schafer said, “We’ve learned that transitioning to organic has as much to do with adding to a farmer’s technical skills as it does with a transition of the soil ecosystem.”

“In year two, the field technicians at the sites have learned more about how organic fields perform and react to practices, and the land has begun to reduce its weed pressure and improve soil health, leading to healthier crops,” he added. “These are variables that are not easy to isolate for measurement … but the overall effect is of improvement year-to-year. We still must see what will come of the crop this year, and we are at the mercy of weather, but, if theory holds true, next year should be better still.”

As UA’s Popp noted, the project is providing a preview of the promise and potential for increased economic opportunities in organic agriculture. For farmers like Martin-Moats and her community of growers, the data and prospects for expanded organic farming locally and across the region could make all the difference – for the economy, and the Earth.

Related Projects