Podcast series amplifies Winrock’s work advancing organic agriculture in the U.S.

Joseph Schafer, a Winrock International program manager overseeing a USDA-funded project that is collaborating with universities, regional and local partners to explore the agronomic and market potential of organic row crops in the Mid-South, is candid in his assessment of how things have gone, so far.

“The goal is to make organic farming economically viable for farmers in this region,” Schafer says in a recent episode of a podcast series featuring the four-year Winrock project, Advancing Organic Agriculture in the Mid-South. The project is testing practices at experimental and demonstration organic farm sites in Arkansas, Missouri and Tennessee. “This region presents unique challenges to organic production. We have a warmer climate, higher temperatures, more precipitation… and that can be coupled with periods of dry conditions as well as a lot of weed and pest pressure” compared to other regions where organic agriculture is already – or better − established.

Another major challenge is the lack of a consistent and large enough market for organically produced row crops in the region, chimes in Kelly Cartwright, executive director of the Natural Soybean and Grain Alliance, one of five key project partners along with the University of Arkansas, the University of Missouri, Tennessee-based Agricenter International – a nonprofit agriculture research and education organization – and the Dale Bumpers Small Farms Research Center in Boonville, Arkansas.

“In addition, we don’t have a lot of infrastructure for organics here in Arkansas and throughout the Mid-South. A lot of the buyers and a lot of the markets are really up toward the Midwest and more toward the Northeast,” Cartwright adds.

Schafer, Cartwright and other experts involved with the project have been sharing insights and knowledge gained – including some hard lessons – as they head into the project’s final year.

The podcasts are produced by the Center for Arkansas Farms and Food as part of the USDA’s Transition to Organic Partnership Program, which provides technical assistance and is helping to build a network that supports organic and transitioning-to-organic producers with mentorship, resources and other information across the U.S.

The AOAMS episodes help disseminate vital knowledge gained over the first three years of project implementation, along with information about the many challenges encountered.

So far, Schafer has appeared in two AOAMS-focused episodes − one in late June and another in late March − with two more scheduled. Schafer says AOAMS hopes to help fill a gap in knowledge about the prospects for growing organic row crops using carefully managed, controlled practices in the Mid-South region, where comparatively little research and demonstration has been conducted or published previously. While AOAMS is focused on Arkansas, Missouri and Tennessee, the broader Mid-South region also includes parts of Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi and northwest Georgia.

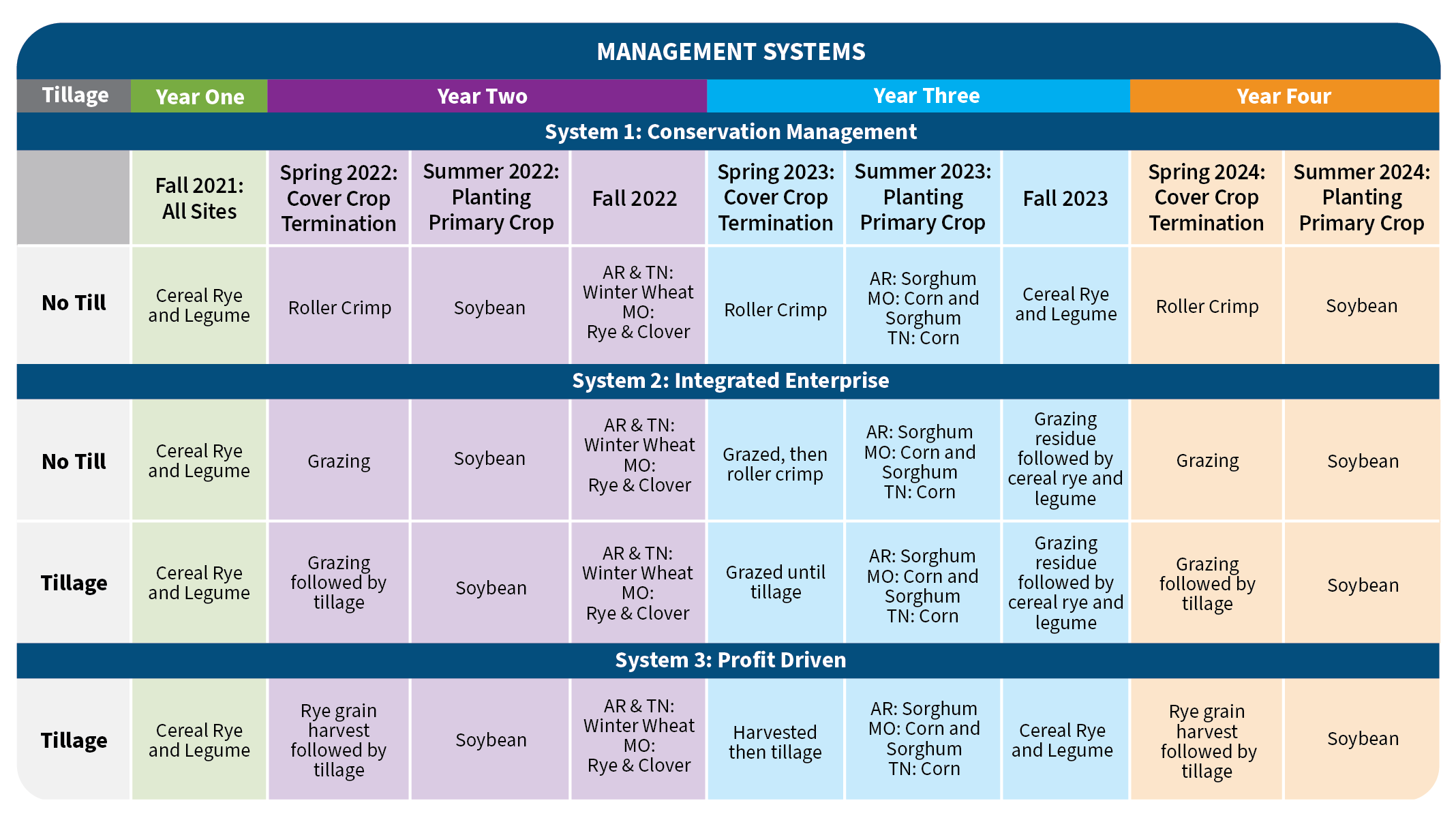

Crops cultivated under a range of varied organic production practices include organic varieties of corn, sorghum, soy, rye and winter wheat, interspersed with organic cover crops.

Schafer has been joined in the sessions by technical experts involved in the project including Cartwright and Lanny Ashlock − known as “Mr. Soybean” in Arkansas due to his expertise and long career as an extension soybean specialist with the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture. The podcasts are part of AOAMS project outreach, aimed at sharing information as widely as possible about organic row crop production in the region, as well as market considerations for producers interested in pursuing organic certification.

One significant update shared in Episode 19 of the podcast series: Year 3 results showed that at project sites, conventional tillage of organic row crops proved more effective than no-till practices at organic plots; this proved to be the case at all sites across the first two years, Schafer says.

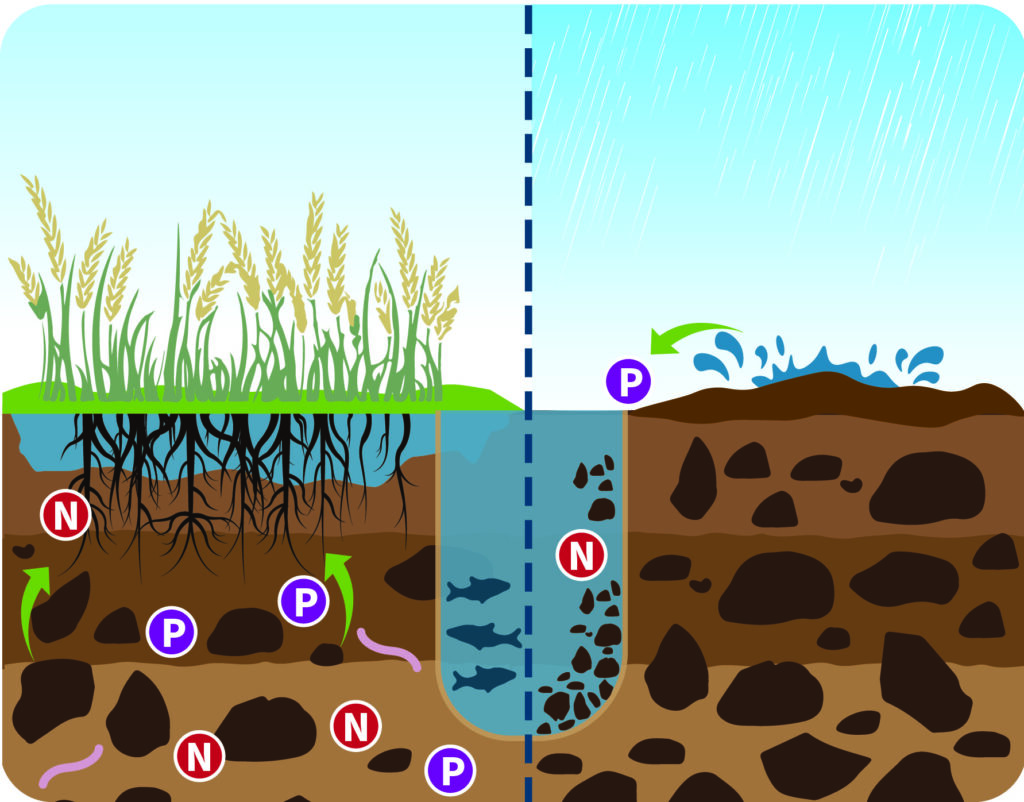

No-till cultivation is important in organic farming because it minimizes disturbance to the soil. Farmers who practice no-till instead rely on the use of cover crops, grazing, crop rotation and special equipment like roller crimpers to flatten crops and produce a mat of vegetation to nourish soils and prevent weed growth. No-till farming is considered a climate-smart practice because it increases soil’s capacity to retain carbon and moisture. In comparison, conventional tillage leaves topsoil exposed, resulting in dryer soils that are more susceptible to wind and erosion. Conventional tillage also releases greenhouse gases stored in the soil and uses more fuel, according to USDA.

In the Mid-South region, growing seasons are hot – and getting hotter − often combined with high humidity mixed with either excessive rains, periods of drought, or some of each. As a result of these and other conditions, Schafer says, “no-till [practices] struggled more than we thought… it’s an avenue for exploration and research.”

Cartwright agrees, citing what he described as the Mid-South’s “supremely challenging” conditions for organic production, which prohibits use of chemical weed killers, insecticides and fertilizers. Another important lesson learned in the project so far: the importance of starting organic crops as early as possible, especially for organic soybeans.

“Prior to initiation of this project, as far as soybean production in the Mid-South, our highest yield – not necessarily the best seed quality but the highest yield − has been obtained with earlier than conventional planting dates, which we used to think was the middle part of May or the month of May,” soybean expert Lanny Ashlock explains in the June episode.

“The highest yield and all the research pretty well documents… if you can plant the soybeans in April you’re set up for the highest yield because we normally get the soil moisture and rainfall events in April, May and up to Mid-June, and then it becomes a lot more sporadic. For non-irrigated, go with early maturing, with early planting dates.”

Despite the challenges and adaptation required, for Mid-South farmers who are willing to be patient, ask questions, evaluate the data and experiment, the potential payoff of transitioning to organic can be substantial. Recent statistics show that consumer demand for organic produce is growing annually: In 2023 alone, the Organic Trade Association reported a record $70 billion in sales of organic products in the U.S. Combined with its smaller carbon footprint, ability to conserve soil health and better protect air, water and ecosystems, exploring organic production – even in the Mid-South’s harsh conditions – makes sense.

“The economics of organic production are strong, and if it’s successful, these farmers can really improve their bottom lines,” Cartwright says. “We have a lot to learn about how it can be done successfully and consistently. The potential is there… but it’s a learning curve that can pay some real dividends in the end.”

Funding for the AOAMS project is provided by the USDA National Institute for Food and Agriculture through the Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative.

Related Projects